The line of trees appears to fragment and disappear as it moves towards the Russian positions on the outskirts of the small town of Velyka Novosilka.

Dima, an infantryman from the ukrainian army in the 1st Separate Tank Brigade, he walks carefully down a path where military boots wear down among spring clover. The zero line, the final trench, is ahead. AND Russian troops are only 700 meters away.

LOOK: The syndrome invented by some Italian doctors that saved dozens of Jews from the Nazis

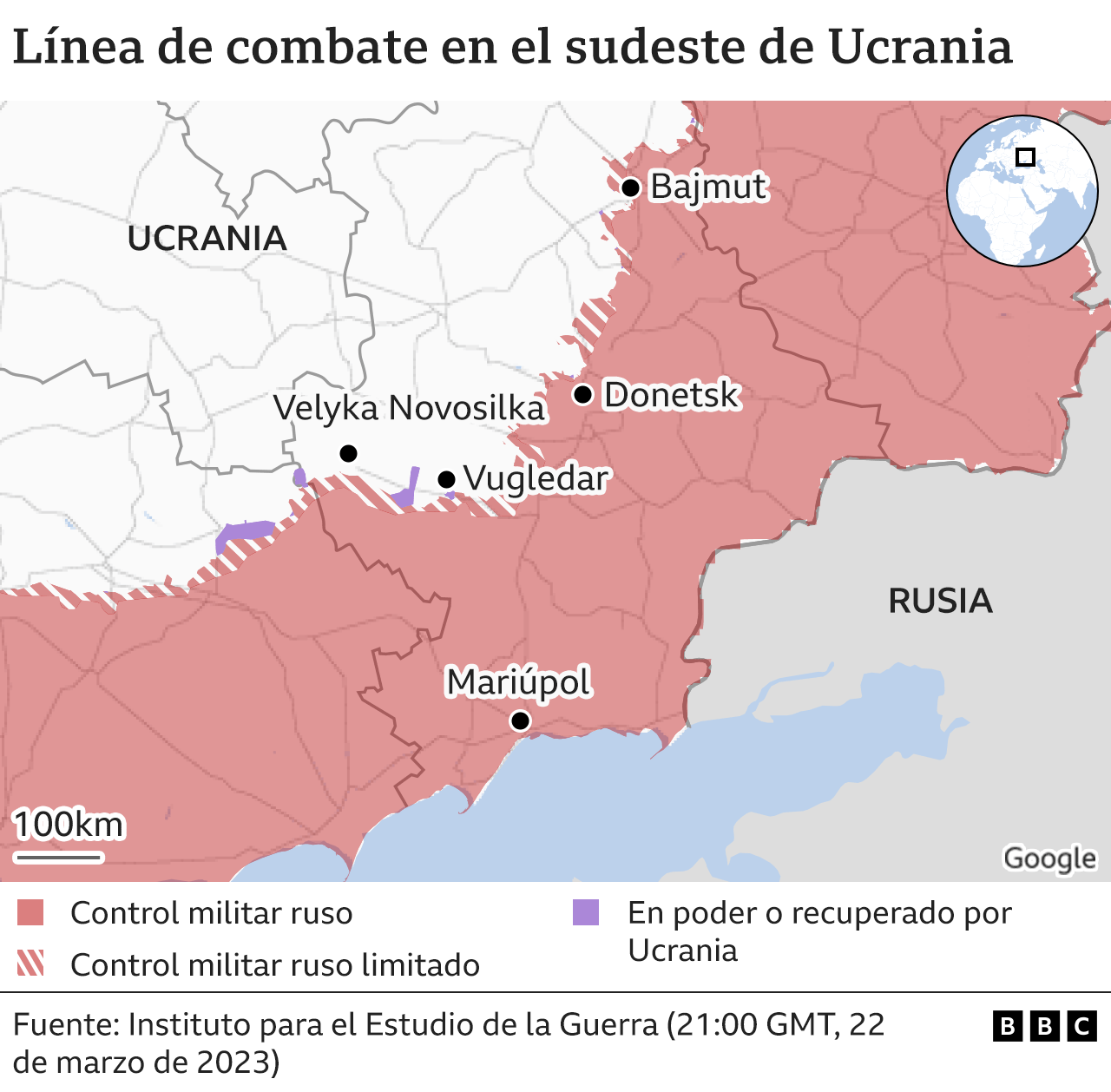

Further north, in bakhmut, the Ukrainians have been losing ground. But here, in the southern Donetsk province, Ukrainian tanks and infantrymen are holding their ground.

Despite months of fierce Russian attacks, Dima says the brigade has lost less than 10 meters of territory. Russian forces, he claims, have suffered heavy losses.

A distraction can cause death

It is a destroyed landscape, where trenches are exposed to Russian observation posts and surveillance drones. On this battle front, Russian eyes are always watching, waiting for an opportunity to attack.

As we pass the infantry trenches, the clover begins to disappear and is replaced by mud and bomb craters. Land mines and unexploded shells litter the ground. The treetops, still bare from winter, are now split and shattered. “There was a tank battle here recently,” Dima assures, “we pushed them back.”

A soldier in a trench shovels soft, red dirt almost soundlessly. From a nearby town, the sound of automatic gunfire comes on the breeze.

“There were often battles in the village. Sometimes the whole village was on fire. They would throw phosphorus, or I don’t know what they would throw,” Dima explains. She is over 6’1″ tall with pale blue eyes that are made brighter by the dark circles below them. His AK-47 it is slung over his shoulder; dangling from his bulletproof vest are a spoon, a can opener, and a small pair of pliers.

The danger here is out of the trenches. A moment of inattention while someone smokes a cigarette can end in death if a mortar or grenade falls nearby. “In general, they shell every day,” Dima says, indicating the Russian positions. These men suffered casualties recently, but they are a fraction compared to the Ukrainian losses in hand-to-hand combat at Bakhmut.

Suddenly, a shell whistles over our heads and lands to the left of our group. The six of us ran for cover and fell to the ground. I lose sight of Dima, but someone yells that a Russian tank is firing. A second explosion occurs, covering me in dirt. It was closer this time, perhaps ten feet away. I make my way to the deck and see Dima standing in a trench. Inside is a covered wooden shelter that four of us get into. As Dima lights a cigarette, another explosion is heard nearby.

“Simply have an unlimited amount of projectiles“, he says. “They have full warehouses. They can shoot all day and won’t run out of shells. But we? We’ll run out of shells this year. So we are forming several assault brigades and they have given us tanks. I think with those we will win. we are fierce We are brave. We can handle it.”

When their positions come under attack, he explains, they take refuge in trenches, while a soldier stands guard looking for enemy infantry and drones. Dima claims to have learned to cope with the situation. “There was fear the first few times. When I first came. Now everything has somehow melted away. It’s become as solid as rock. Well, there are some fears; everyone has them“.

Another shell lands close enough to make him jump. “That was good,” he says, shaking his head and dusting himself off.

“When the infantry is being wounded, the tanks come”

Dima is only 22 years old and is from the central industrial city of Kremenchuk. She worked at a petrochemical plant before the war and, like many of the soldiers fighting here, her adult life has only just begun. When she asks what she says to her family, she replies, “I don’t have a family yet. I have my mother, I don’t have anyone else for now.” She calls home twice a day, in the morning and at night. “She doesn’t know much, I don’t tell her everything“, he counts as his voice trails off.

Among the soldiers there is disagreement about what the Russians are shooting. It could be tank, mortar or grenade fire or a combination of all three. A bearded soldier, grubby from days at the front, enters the dugout and makes a twirling motion with his finger. A Russian drone flies over. Even here there is uncertainty, it could be armed or it could be a reconnaissance drone. There is nothing to do but wait until the shelling ends or it gets dark.

I leave the men just after sunset. The brigade’s tanks are firing on the Russians now, and as I return, a new turn of soldiers takes up positions along the trenches. I keep an eye on the dim light from where I pass, remembering the lethal mines in the entry route.

Tanks and artillery dominate here, with the Ukrainian-made T64 Bulat tanks They operate every day. “The troops in the tanks are like the big brother of the infantry,” says tank commander Serhii. “When the infantry is being wounded, the tanks come. But the problem is that we can’t always come.”

About the “enemy”

The 1st Separate Tank Brigade is one of the most decorated in the army. Its commander, Colonel Leonid Khoda, is awaiting the arrival of the western tanks, including the British Challenger IIand has already sent men to train in the german leopards.

The enemy “has a completely different objective,” he says. “We protect our state, our land, our relatives, we have a different motivation. They have no way out. (…) They don’t go back. Because going back means prison, it means execution. So they are advancing like lambs to the slaughterhouse.”

In February, the Russians attempted to break through the fighting front 30 kilometers away, a bold move that would have put the rest of unoccupied Donetsk at risk. The advance ended in catastrophe, with hundreds of Russians killed, dozens of their tanks lost, and an armored brigade nearly wiped out.

Remembering the progress of the February attacks around the city of vugledar, 13 kilometers away, Colonel Leonid Khoda describes it as “an act of desperation.” The enemy brigade was effectively wiped out, he says, “but lately they have started to change tactics.”

Donbas

Much of the Donbas it is filled with grit from the industrial age. Vast abandoned factories and monumental mountains of rubble dominate the landscape, but not here. The land that Colonel Khoda’s men are specifically protecting is the market town of Velyka Novosilka.

Before the war, the town had a modern school, a tidy fire station, and a three-story kindergarten. All are now abandoned and destroyed.

The army driver taking us to town makes a detour to avoid a rocket embedded in the road. Another Russian shell lands in a nearby neighborhood, sending a long arc of dirt into the gray sky. The small town houses and cottages flash past the window, and though broken, it’s easy to see that this was a prosperous town before the war.

About 10,000 people used to live here, now there are less than 200. “Now only mice, cats and dogs thrive here and also hide from shelling,” says one of the soldiers in the car.

In one of the shelters I meet Iryna Babkina, the local piano teacher who is trying to hold together the remaining threads of her village. With bright red hair, she’s quietly determined to stay in town. A few dozen residents live in the cold, damp shelter, and Iryna helps take care of the elderly.

She describes what has happened to the town as something akin to a “mourning” feeling. “It used to be such a beautiful place,” she says. Now “it’s more of a sadness: the sadness of what used to be, the sadness of what it is now.”

In the shelter, in that dimly lit basement heated by a wood stove, I hear a voice. Sitting alone on a bed is 74-year-old Maria Vasylivna.

Before Iryna introduces us, she whispers, “It’s hard for her to talk, her husband died from a shrapnel recently.”

Maria takes my hands. “Oh, you’re cold,” she says, warming them between hers.

Her husband, Sergiy, 74, was too sick to go to the shelter and stayed at home even as Russian bombs rained down on the neighborhood.

She tells me quietly, “He bled to death overnight. I was here and he was home. I came in the morning and he was gone. We buried him and that’s it.” They had been married 54 years.

Before I leave, Iryna takes me to the village school. Its lilac-painted corridors are littered with rubble and windows have been smashed by Russian bombs. The children’s jackets still hang on the hangers and homemade Christmas decorations sit unpicked on a shelf.

On one wall above a pale blue radiator, a group photo shows the children’s soccer team celebrating a victory. Looking out the window you can see the same field as in the photo but with craters and the nearby handrails are destroyed by bombing. An unexploded Russian rocket tail fin protrudes from the asphalt of the playground.

There is a piano in the hallway and Iryna sits down to play it. But no melody comes out, the piano is badly damaged. She has no music to play and no children to teach. The latter were forcibly evacuated from the city by police last month and taken to a safer location. His own daughter was among them.

“There are only shell sounds,” she says. “The school is destroyed, the instruments are ruined, but it’s okay, we will rebuild it and the music will play again, along with the laughter of the children.”

These are the ties that unite people here, be they civilians or soldiers. The conviction to resist is the enduring weapon in Ukraine’s arsenal, as vital to the country’s survival as any armored tank or infantry trench.

Source: Elcomercio

I am Jack Morton and I work in 24 News Recorder. I mostly cover world news and I have also authored 24 news recorder. I find this work highly interesting and it allows me to keep up with current events happening around the world.

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/GE2TANJNGAZS2MRXKQYDAORRGU.jpg)