In 1432, a work was unveiled that left magnificent evidence of the immense artistic leap that the Renaissance meant, even though it happened a century before the official start of that cultural movement.

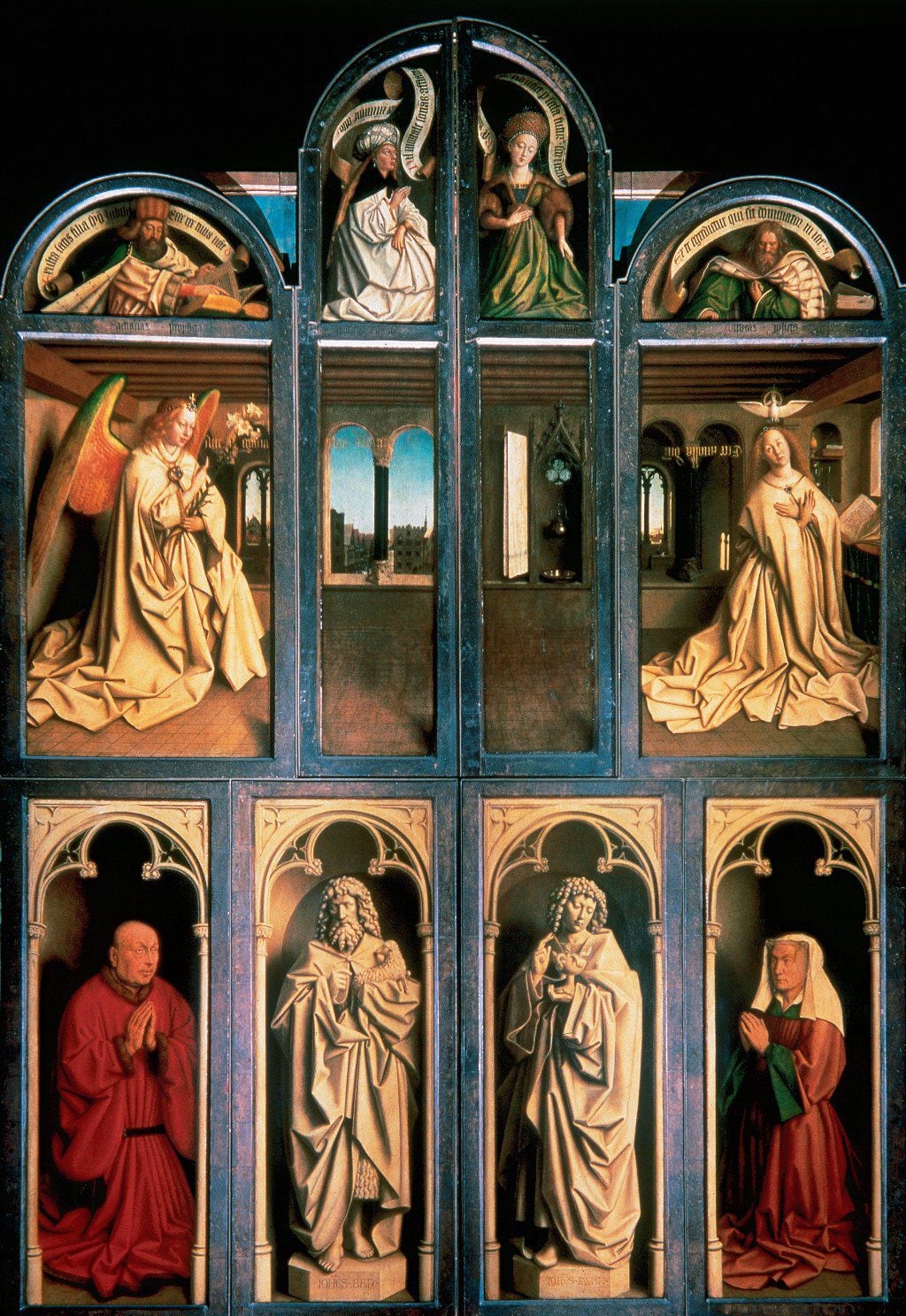

We are talking about a polyptych masterfully painted by the Flemish brothers Hubert and Jan van Eyck for the present cathedral of Saint Bavo, in Ghent, Flanders (today Belgium). It was a huge work of approximately 4.4 x 3.5 meters in dimension.

LOOK: Pinin Brambilla, the woman who spent more than 20 years restoring “The Last Supper” and amended Leonardo’s “big mistake”

With its 12 oil panels, the Ghent Altaralso know as “The altarpiece the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb”, showed the public for the first time images that almost perfectly portrayed the real world.

The polyptych immediately astonished and captivated the spectators of the time, who proclaimed it “the most beautiful work of Christianity”, and Jan Van Eyck (his brother died before completing it) was declared the prince of painters.

Each figure had its own expression; her skin, pore and hair had been individually painted, as had each strand of hair, each wrinkle, each vein.

The plants were the same that they saw around them, faithfully represented in the garden where an altar to the Lamb of God was worshipped, a symbol of Christ’s sacrifice for humanity.

Around the Fountain of Life, the earth was littered with precious stones so translucent and brilliant that Van Eyck was suspected of having discovered a secret alchemical process.

And somehow, it was true.

with own light

If the alchemical dream was to turn any material into gold, Van Eyck turned pigment into that metal and precious stones more skillfully than any other painter of the time. using layers of paint to create deeper, richer colors, and different oil-based glazes to give them radiance.

All done and applied with incredible care, so that everything depicted would reflect light in the same precise and distinctive way as it would in reality. This is the case with the altarpiece itself, but also with the frames between the panels.

Everything was different from the painting that preceded it.

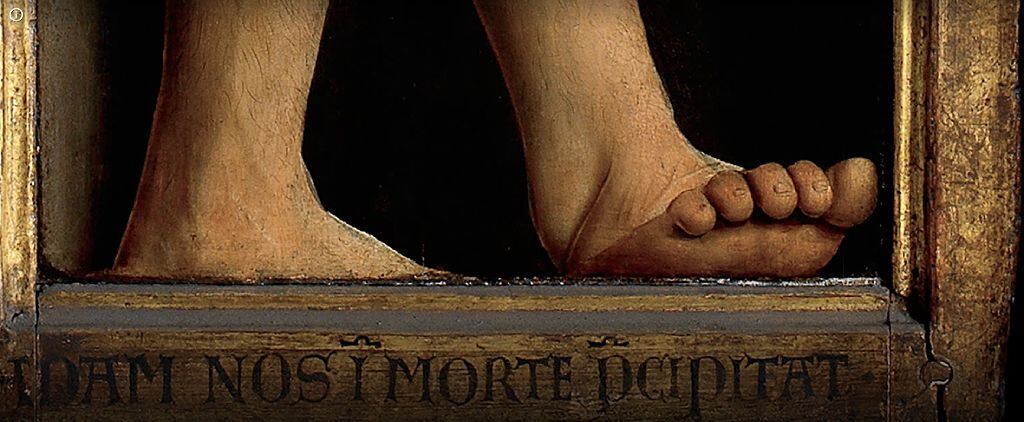

Take, for example, one of its many wonders, perhaps the most praised: the figure of Adam.

For first time observers, it looked like a living being, and not only because of its size.

In his eyes, the glint of light coming through the window, absent in the eyes of Eva, who stands on the other side of him with her back to the opening.

Van Eyck captured the minute subtleties of the skin.

Blood seems to pulse beneath her, and her hands and face are visibly tanned by the sun.

Such was Van Eyck’s desire to represent reality that this was the first time they appeared nude with pubic hair in art.

And a detail intensifies this appearance of reality.

The big toe is raised and seems to be coming out of the stone niche where the figure stands, as if Adam was about to enter our world.

For these and many other delicacies it was and continues to be considered one of the splendors of the Western artistic tradition, as well as a milestone that marked the transition between the art of the Middle Ages and that of the Renaissance.

spoils of war

Less than 100 years after it was unveiled, the Ghent Altar was already a tourist attraction, with visitors paying high fees to see it.

Many artists acclaimed it, including the leading German Renaissance painter Albrecht Dürer, who after seeing it in 1521 declared it a “priceless painting of deep understanding”.

It also quickly became one of the most coveted works in the world, earning the unfortunate distinction of being the most stolen work of art in history.

The history of the misfortunes of the polyptych did not begin with a robbery strictly, but with a threat of its complete destruction.

In 1566, Protestant militants broke down the doors of the cathedral with the intention of burning itas they considered it an example of idolatry and Catholic excess.

You arrived late. He had already been dismounted and hidden in the cathedral tower, where he survived unharmed.

During the following centuries, spoils of war went several times.

Historically, the largest art thefts have not been carried out by individuals but by armies, not exactly for money, but out of the desire to reclaim the art of a vanquished nation.

In 1794, the invading Napoleonic troops carried away the central panel with the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb and ended up on display in the Louvre (then Musée Napoléon) until the British defeated Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo (1815).

Restored to his throne, Louis XVIII returned the stolen pieces to Ghent in gratitude for having protected him.

In 1816, under unclear circumstances, six panels from the Altar wings were sold and, after sales and re-sales, they came into the hands of the king of Prussia in 1821who passed them on to the Kaiser-Friedrich-Museum in Berlin, where each was cut vertically down the middle.

This time they were returned as a condition of the Treaty of Versailles (1919).

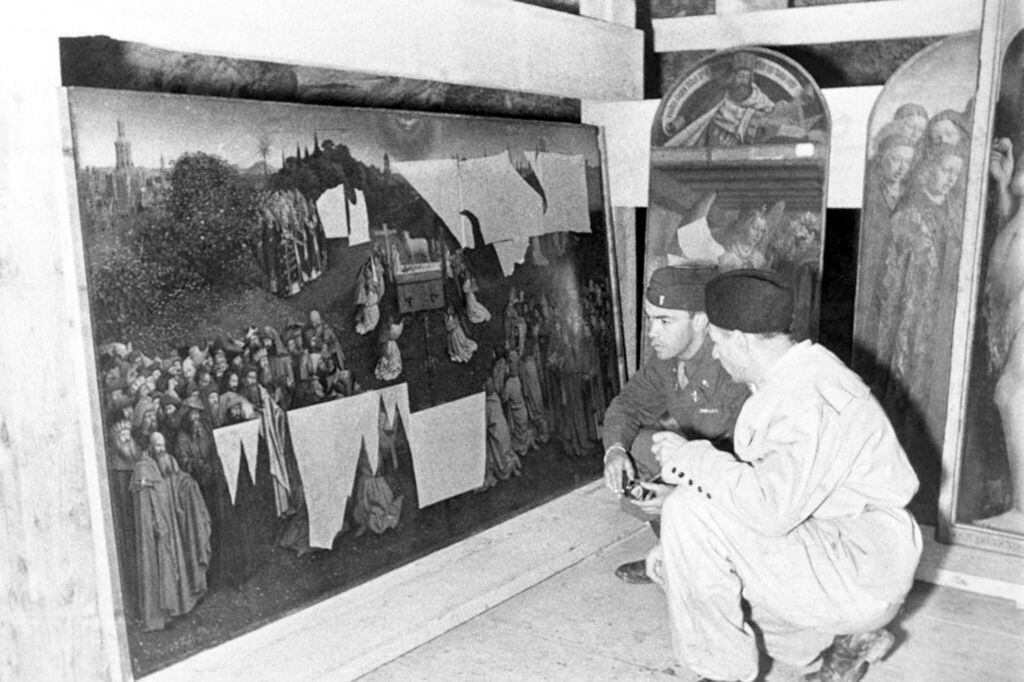

Then came World War II.

So much Adolf Hitler as Nazi party leader Hermann Göring desperately wanted artworkapparently because they were convinced that it was a coded map of the mystical treasure that showed the location of the relics of the passion of Christ, which would grant them supernatural powers.

If that was the reason, it is striking that after finally stealing it on its way to the Vatican for safekeeping in 1942, the Nazis exposed it to irreversible deterioration by carelessly hiding it with thousands of other looted works destined for the planned Führermuseum in a salt mine in Austria.

It was saved from total destruction thanks to some miners who, aware that the order was to blow up the cave if the allies arrived, risked their lives to defuse the bombs.

Finally, it was rescued and restored by the MFAA unit (for the acronym in English of the Monuments, Art and Archives Program, known as Monuments Men).

But there’s a panel that even the mighty Nazis couldn’t steal… because it had been stolen before.

The great theft

On the night of April 10, 1934, passersby saw two men dressed in black carrying something flat wrapped in cloth, getting into a waiting car and disappearing into the darkness.

The next day, the cathedral sacristan discovered that the panels of the Just Judges and John the Baptist were missing.

what followed was so far fetched it seems like a work of fictiona thriller without end.

In the frame of the altarpiece there was a note with the text “Taken from Germany by the Treaty of Versailles” written in French.

The police did not find any useful traces.

19 days later, the Bishop of Ghent received a ransom demand of one million Belgian francs – about US$1 million today -; the letter hinted that Germany had nothing to do with the matter.

The authorities refused to pay, but the bishop continued to negotiate with the signer, and with the third letter came a receipt for storing something at a train station in Brussels: turned out to be the panel of John the Baptist.

The next letter contained a torn newspaper page and said that whoever was to collect the ransom would appear before a parish priest with the other half of the page as a token of identity.

If they gave him the required money, he would return the other panel.

The blackmailed followed the instructions, but only put a quarter of the requested amount in the envelope.

The thief was enraged.

The last letter arrived on October 1.

The last sigh

Weeks later, 57-year-old stockbroker Arsène Goedertier suffered a heart attack.

On his deathbed, he confessed to his lawyer that he was the only one who knew where the original panel of the Just Judges was hidden.

And his last words were: “desk, key, cupboard, folder marked ‘mutualité’.”

The lawyer found carbon copies of the ransom letters, plus an unsent one, with a tantalizing clue to the whereabouts of the stolen panel: “[está] in a place where neither I, nor anyone else, can take it without going unnoticed”.

It took a month for the lawyer to communicate what had happened to the police who, after following several false leads, concluded that Goedertier had been the thief.

But why, if he was rich and devout?

And, more importantly, where are the Just Judges?

the great mystery

For decades, theories and speculation have surfaced regularly, and hundreds of leads have been received and investigated by authorities as well as amateur detectives.

So far none have paid off.

However, some details have come to light, such as a story unearthed by Karel Mortier, former chief of the Ghent police, about something that happened during World War II.

10 years after the robbery, the Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels sent an art detective, Heinrich Köhn, to Ghent in search of the missing panel.because he wanted to give it to Hitler.

Köhn concluded that the panel was simply hidden in the cathedral, but that it had been moved before he arrived so that it would not fall into his hands.

This idea that it was still there, and even in plain sightas Goedertier seemed to indicate before he died, has led St. Bavo’s Cathedral to be searched from top to bottom six times since World War II and even taken X-rays of it at depths of 10 meters.

It was also thought that the excellent copy made in 1945 that still marks its place was actually the original panel, but science proved that this is not the case.

The whereabouts of the Just Judges in the masterful triptych by the Van Eyck brothers remains one of the great mysteries of art history.

Source: Elcomercio

I am Jack Morton and I work in 24 News Recorder. I mostly cover world news and I have also authored 24 news recorder. I find this work highly interesting and it allows me to keep up with current events happening around the world.

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/GIYTCMJNGA2C2MBZKQYDAORSGE.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/ATPCK5WCTRBJTGCXXMB4FE3VNU.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/LCECPSH6QRGVPPQH72OQDZ7YQE.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/PACZDYY5MNGHPI66HA3R2A6QT4.jpg)