On May 29, two thirds of the Colombians they voted for a change; by a rupture with the political class that has governed for centuries. 14 million people said “no more”.

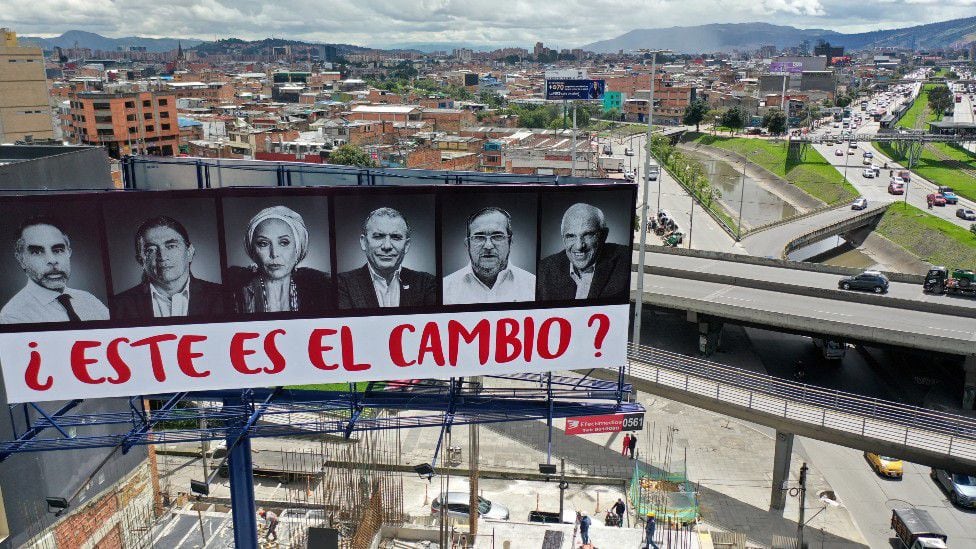

But they voted for two types of change: a more ambitious one, promised by Gustavo Petro, who seeks to be the country’s first leftist president; and a more pragmatic one, proposed by Rodolfo Hernandezan independent, nonpartisan candidate obsessed with fighting corruption.

LOOK: 3 controversies that have clouded the election of the new president of Colombia in the last days of the campaign

Both are enemies of traditional politics, they were built as an antithesis to “the usual” and have rupture speeches.

But the economist and former guerrilla Petro and the engineer and construction tycoon Hernández, who are facing each other this Sunday for the presidency, do not share the forms or the diagnoses or the political projects.

Both accuse the other of being “continuationist“. And are assumed as “the actual change“.

“So many years of a system run by them and that doesn’t work for the majority have been more than enough; change is the feeling and the struggle of all of Colombia,” Petro said this week.

And Hernández put it this way: “The choice is simple: vote for someone who is controlled by the same people as always, or vote for me, who is not controlled by anyone.”

Petro is running for the presidency for the third time. He has spent 40 years building a political framework to make history. He started out as a guerrilla. He later became a successful senator and controversial mayor of Bogotá. Against him is the rejection of a large part of the population.

Rodolfo Hernández was practically unknown at the national level six months ago. But in his land, Santander, the “engineer” has been building a construction empire for years. He was mayor of the capital, Bucaramanga. And his main card —which in the “beautiful city” he partly succeeded in— is “wiping out corruption.” Against him they play his ignorance of the State and that on July 21 he is called to trial for a case, precisely, of corruption.

What they agree on is that the next president of Colombia will be a “populist.” Experts consider Petro an anti-oligarchy nationalist populist; and Hernández, an anti-political neoliberal populist.

To win, both Petro and Hernández had to ally themselves with members of the disgraced political class, although they deny this. During the dirty and frenetic campaign for the second round, the speeches of both were contradicted by their own actions, reflected in old and recent files published by the media. Little was said about the programs.

What was manifested on May 29 can go down in history as a cry for independence, one of the people fed up with their political class. But it can also be a cry that was not attended to.

Two changes: one ambitious and one pragmatic

Petro and Hernández went to the second round thanks to their proposals for change, but in these three weeks the differences between them were more evident every day.

The change of Petro is from background and long term. Hernandez’s is from shapes and focused on corruption.

Although he has said that he will not seek re-election, Petro believes that his political project needs several governments along the same lines to achieve his goals, which involve profound reforms in areas as complex as land ownership (he wants to deconcentrate it), of health and pensions (he wants to separate them from the private sector) and the productive model of the country (he wants to move from extractivism to industrialism).

Hernández’s project, on the other hand, does not propose a temporality beyond the four years that could mean the presidency of a 77-year-old leader. His main cards are to put an end to corruption through rigorous surveillance systems for state concessions and contracts, and reduce bureaucracy, closing embassies and consulates and merging ministries. In the economic sphere, he believes that by eliminating the “obstacles and robbery” employment, competition and growth will be generated and that by reducing public spending it will be possible to invest more in the social sphere.

The idealistic Petro proposes to make great reforms in almost all the subjects. The austere Hernandez just wants things to work the way they should.

“Petro seeks a cultural change and a state that takes strong action to ensure equality,” says political scientist Mónica Pachón. “A larger state, with more guarantees, with a broader provision of services; something that necessarily implies increasing state spending and bureaucracy.”

Rodolfo Hernández is almost the opposite, according to the professor at the Universidad de los Andes: “A world in which people can rise and prosper without obstacles; a modest State, but above all efficient and without bureaucracy.”

The also political scientist Gustavo Duncan, who has written about the types of people that both populists “invent”, adds: “All populists base their speeches on the idea of change and of an imaginary, ideal people.“.

“The one that Petro invents is an excluded town that seeks to stop being poor through subsidies and political participation, while the one that Hernández invents is a parochial and hard-working town that fears that they steal what they have earned or can earn with their work. “.

“The Petro thing is ambitious, and that is why it has more potential to go wrong, and the Hernández thing is more precarious, but for that reason more achievable,” says the analyst.

How feasible is the change

Although Petro’s coalition will have a much larger caucus (20 senators and 28 representatives) than Hernández’s (0 senators and two representatives), whoever wins will have to face a fragmented Congress in which it will be necessary to negotiate with other currents.

That negotiation, as was seen during the campaign for the second round, includes the traditional politicians who generate so much rejection. And if in the campaign it was difficult to remain detached from the political class, in government it will be even more so.

In addition to Congress, both would have strong counterweights: the Banco de la República, the media, the courts, state control entities and business associations.

Until now, Colombia’s deep-rooted institutions have prevented drastic changes in the state and popular politicians from being re-elected indefinitely, as was the case with Álvaro Uribe. Both Petro and Hernández would have to deal with that institutionality.

This is added to the fact that the cry for change has a diversity of demands that range from economic and democratic rights to social and cultural rights. Ending corruption, inequality and what remains of the war is going to take much longer than four years.

“That’s what populism is all about,” says Duncan. “Of the super promises that, from the outset, are unfeasible”.

Pachón agrees: “The usual thing is that politicians do not keep their promises, because in the campaign everyone sells a vision of what they believe to be the ideal model.”

“What is complex in the current Colombian case is the level of rapacity in which both campaigns are: whoever comes to power will have to deal with a level of animosity and mistreatment in the opposition“, predicts Pachón.

In 2019 and 2021, millions of Colombians went out to protest for a multitude of reasons. They all wanted changes, but different changes. The demands are many, diverse and, in some cases, contradictory to each other. That is why it is difficult to imagine a presidency, whoever wins, that does not reactivate the desire to protest of those who see their demands unsatisfied.

That 14 million Colombians have voted for a change does not mean that they agree. Whoever wins, there are few in Colombia who wait four years without frights.

Source: Elcomercio

I, Ronald Payne, am a journalist and author who dedicated his life to telling the stories that need to be said. I have over 7 years of experience as a reporter and editor, covering everything from politics to business to crime.

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/GE4TCMRNGA3C2MJXKQYDAORRHE.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/63WIYQW7QNFG7DOETU7QNDDMQI.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/4FNJ6KIZQNAW7P3CMD6HC2GUUI.png)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/3BUVSGVV65HBFMVPWYRZS52PMM.jpg)