:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/MAKSO4MGINHFHGVYU62QR57HSA.webp)

Neither “girls”, nor “chicxs”, nor “chic@s”. In the schools of the capital Argentina teachers will no longer be able to use these gender-neutral expressions, popular among youth, to communicate with their students.

The city government of Buenos Aires issued in June a resolution that limits the use of the so-called “inclusive language” in initial, primary and secondary education.

LOOK: Ruja Ignatova, the “queen of cryptocurrency” who swindled US$4 billion, disappeared and is now the most wanted woman by the FBI

The decision prohibits the gender-neutral endings “e”, “x” or “@” from being used in institutional communications and from being taught as part of the educational curriculum.

It also requires that these be carried out “in accordance with the rules of the Spanish language“.

In justifying the norm, the Buenos Aires authorities made reference to the low results obtained by the students of the Argentine capital in the last reading and writing evaluations.

“The distortion of language use It has a negative impact on learning, especially considering the consequences of the pandemic,” they assured from the Buenos Aires Ministry of Education.

“It is very important to clarify well and simplify learning,” reiterated the mayor of Buenos Aires, Horacio Rodríguez Larreta, after the rain of criticism that the measure received.

The resolution clarifies that the prohibition “applies only to the contents dictated by the teachers in class, to the material that is given to the students and to official documents of the educational establishments”, and that students will be able to continue to use inclusive language among themselves.

He even recognizes that it is important “to break with the sexist notions that enable the use of the generic masculine and incorporate a more inclusive language.”

But he assures that “the Spanish language offers many options to be inclusive no need to twist the languagenor to add complexity to reading comprehension and fluency”.

To emphasize the latter, the government released a “guide to practices and recommendations for inclusive communication“.

However, the announcement received much criticism from some educators, linguists and even from the national education minister, whose government is politically opposed to that of the city of Buenos Aires and supports the use of inclusive language.

Several highlighted that there is no evidence that the use of inclusive language has been related to low test results.

“It cannot be forced, much less the use and customs in the language can be prohibited,” said Buenos Aires deputy Alejandrina Barry, who presented a project in the local Legislature to repeal the norm.

What caused the most discomfort was Acuña’s announcement that whoever does not comply with the will face “an administrative disciplinary process”.

Rejection

However, the Argentine capital is not the only one that has spoken out against the use of so-called “language with a gender perspective.”

As cited in its foundations the Buenos Aires norm, one of the first to reject these new neutral terms was what is considered by many to be the maximum reference of the Spanish language: the Royal Spanish Academy (RAE).

In 2020, in response to a request from the then Spanish vice president to modify the Constitution to make it more inclusive, the RAE published a 156-page report explaining its rejection of inclusive language.

“The use of the ‘@’ or the letters ‘e’ and ‘x’ as alleged marks of inclusive gender is alien to the morphology of Spanish“, concluded the RAE.

In addition, he declared himself against the proposal to replace the generic use of the grammatical masculine – which the most critical consider the “symbolic brick of patriarchy” – with more inclusive forms.

“It’s unnecessary, so the generic masculine does not hide the presence of the womanbut it includes her with the same right as men,” she assured.

Since the publication of that report, the RAE has maintained its position.

At the end of 2021, consulted on Twitter by a user about inclusive language, he defined it as “a set of strategies that aim to avoid the generic use of the grammatical masculine, a mechanism firmly established in the language and that does not imply any sexist discrimination“.

Latin America

Although the announcement from the city of Buenos Aires captured media attention, the truth is that the Argentine capital was not the first in the region to seek to limit the teaching of gender-neutral language.

Last January, shortly before classes began in the south of the American continent, Uruguay took a similar measure when it published a circular that stipulates that in the field of public education the use of inclusive language “must conform to the rules of the Spanish language“.

The order issued by the National Administration of Public Education (ANEP) indicates that “inclusive expressions” can be used “as long as those are complied with.”

Like the Buenos Aires resolution, the ANEP clarified that its instructions are aimed at teaching and non-teaching officials and do not affect the forms of expression of students.

Strictly speaking, this regulation was an update of another similar resolution that the body had already issued in 2019.

Beyond the educational authorities, there have been other attempts to stop the progress of inclusive language in schools and other environments in Uruguay.

Last April, deputies from the right-wing Cabildo Abierto party presented a bill to ban “grammatical and phonetic alterations” in public administration and in public and private educational centers.

“The purpose of the same is that words are not modified to make them ‘inclusive’ with the E, the X or @”, specified the deputy Inés Monzillo on her Twitter account.

“Let’s speak our language correctly“, he ruled on his project, which generated “concern” on the part of the Teachers’ Association of the University of the Republic (ADUR).

Other countries in the region, such as Chilihave also seen the emergence of legislative proposals that seek to stop the progress of inclusive language.

France

But Spanish is not the only language that differentiates between masculine and feminine, and that has seen the emergence of new (and controversial) neutral expressions that seek to make it more inclusive.

And it is not the only language that the most purist authorities have tried to “preserve” from the inclusive language.

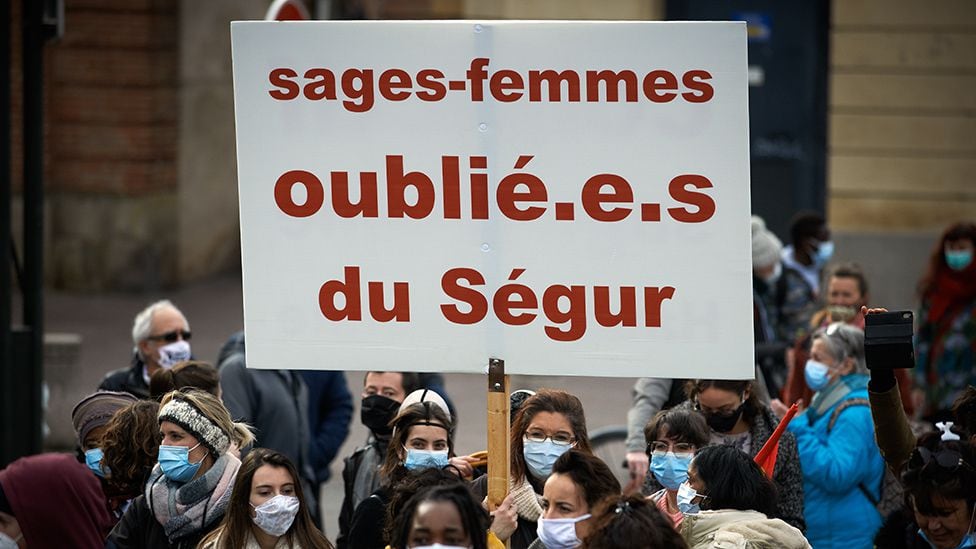

In fact, the country that has most strongly lowered its thumb for now to language with a gender perspective is France.

There was his own Minister of National Education, Jean-Michel Blanquerwho signed a circular in May 2021 that prohibits the use of inclusive writing in class.

Unlike what happens in Spanish with the endings “e”, “x” or “@”, in French the most used tool to impart neutrality is a middle point (•).

This is used to give a word both masculine and feminine endings, simultaneously.

Take for example the word “to my” (friends). The inclusive way to write it would be: “friends“, which combines the masculine version (“me“) with the feminine (“friends” or friends).

It would be something similar to the Spanish “amigos/as”.

Blanquer prohibited the use of the midpoint in schools, arguing that “the impossibility of orally transcribing texts with this type of spelling makes both reading aloud and pronunciation difficult and, consequently, learningespecially the little ones”.

In addition, the minister pointed out that “it constitutes an obstacle to access to the language of minors who face certain learning disabilities or disorders“.

It is an argument similar to the one used by some critics of the inclusive Spanish language, who claim that it makes it difficult for people with dyslexia or blindand therefore, rather than include, “exclude”.

Like the Buenos Aires rule, the French ban did not reject all inclusive language, but sought to promote other ways of generating inclusivity, recommending, among other things, “the use of the feminization of trades and functions” .

However, the French authorities made their opposition to the use of gender-neutral words clear when, at the end of 2021, the well-known Petit Robert dictionary included the pronoun “iel“which combines “he” and “she” and is widely used by people of non-binary gender.

Not only Blanquer shouted to the heavens, but also the French first lady, Brigitte Macron, got involved in the controversy, stating that with two pronouns it was enough.

“Language in Motion”

Despite the resistance, there are many who assure that the limitations and prohibitions will not be able to prevent inclusive language from being imposed.

The editors of the famous French dictionary themselves explained, in the face of controversy, that they were simply reflecting a phenomenon that already exists.

“Le Robert’s mission is to observe the evolution of a French language on the move, diverse, and report on it“, they explained through a statement.

Even the RAE itself recognized that, ultimately, the language that is imposed is the one that is spoken on a day-to-day basis and not the one that they dictate.

“It is opportune to remember that the grammatical or lexical changes that have triumphed in the history of our language they have not been directed from superior instances, but have arisen spontaneously among the speakers“, he pointed out in his report on inclusive language.

“It is the latter who promote and adopt linguistic innovations that only sometimes achieve success and become widespread,” he clarified.

During a recent visit to Chile, the director of that academic institution, Santiago Muñoz Machado, reiterated this idea, stating that “it is the citizens, by using the language, who establish the rules.”

In an interview with the Chilean newspaper El Tiempo, Muñoz Machado also admitted that “the RAE is always a little behind the citizens“.

For her part, the renowned Argentine writer Claudia Piñeiro, who in 2019 was one of the first personalities of letters to defend the use of inclusive language during a speech she gave at the International Congress of the Spanish Language, considered that trying to regulate it is futile.

“Wanting to ban a language is like trying to grab water with a strainer,” he said after the announcement by the Buenos Aires government.

Piñeiro, who in his speech recognized that only “in the future” will we know if the inclusive language will end up being “adopted by the Spanish language”, also observed that the prohibitions will surely have the opposite effect desired and end up making more young people want to use it.

Source: Elcomercio

I, Ronald Payne, am a journalist and author who dedicated his life to telling the stories that need to be said. I have over 7 years of experience as a reporter and editor, covering everything from politics to business to crime.