When in December 2021 gabriel boric won the second round of the presidential elections, the chronicles about the 35-year-old president-elect emphasized that this young man of Croatian ancestry had gone from student leader at the University of Chile to president in just over a decade.

Although not all Latin American student movements can say that they have put one of their leaders in the highest political position in the country, many young university students in Latin America have participated in the marches, protests and movements who have changed the politics of their countries.

LOOK: 3 questions to understand how the new Constitution of Chile will be written after the overwhelming rejection in the previous process

Colombian students were direct protagonists of the 2021 national strike that would influence the coming to power for the first time in Colombian history of a left-wing president, Gustavo Petro. Ecuadorian universities, for their part, were humanitarian aid zones in the indigenous marches of 2022.

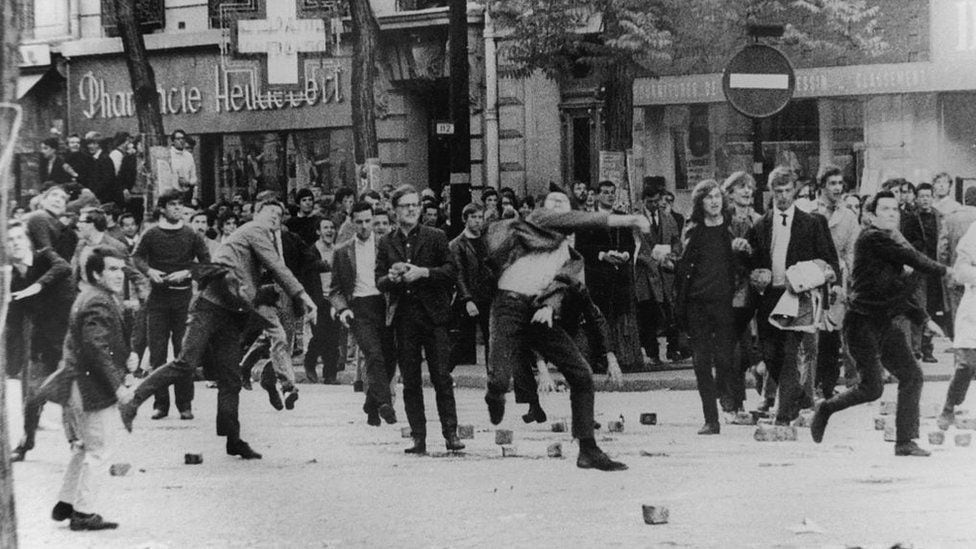

This history of social struggle, political changes and student mobilization in Latin America has a precedent that influenced not only the region but also the young people who in May 1968 wrote on the walls of Paris “imagination to power.”

Half a century earlier, in 1918, a group of young students marched in Córdoba, Argentina, demanding the democratization of the University and wrote a manifesto directed “to the free men of South America” in which they described the political role that students would play from that moment on in Latin American history with phrases like “youth always lives in a trance of heroism.”

To talk about this first student rebellion, BBC Mundo spoke with the Argentine historian Felipe Pigna.

______________________________

What factor triggered that protest that would change life in universities both inside and outside of Argentina?

It actually has to do with many factors. First with the massive arrival of immigrants at the end of the 19th century who clearly came with strong aspirations.

The idea of having a better time than in Europe, of being able to have your land, of being able to progress; and that was transmitted to their children, the so-called son of the gringo, son of the immigrant, who began to be aware that one of the few forms of social advancement that existed in a country with strong inequalities, of rich and very rich and poor very poor, it was education.

Education that power was delivering in drops: first it guaranteed compulsory public education in 1884, but it was basically for primary levels, reserving for that way higher education that was seen -effectively- as a factor of political reproduction, that is, of conservation of his power.

That is why they were quite zealous in keeping the university, even secondary education, limited to certain social sectors; but the demand was growing, it was becoming elements of slogans and social demands.

And when the Radical Civic Union came to power, which is a middle-class political force, its social base demanded the expansion of university studies, the democratization of the houses of study, and this exploded in rebellion in Córdoba in 1918. .

All in a very particular world context, against the backdrop of the Russian Revolution, with a growing support for progressivism.

The horrors that Soviet communism will have after have not yet been seen, but it was the romantic stage of the revolution.

In addition to being children of immigrants, what were those students who carried out the reform like?

It was a profile that we could define as progressive, I would say center-left, some on the left with many ties to the Socialist Party, some to anarchism, which was a very important force at the trade union level in Argentina since approximately 1890, managing a of the most important trade union centrals that was the FORA: the Argentine Regional Workers’ Federation.

They read a lot of literature. It was political literature, but also Argentine literature with writers like Leopoldo Lugones, for example.

And also a lot of information about what was happening in Europe and Latin America.

They were very reading people, regardless of their discipline, understanding that they were immersed in a society and that they had to give an account of their character as citizens, of what it meant to be a citizen.

With a great awareness, which seems very important to me, of the privilege that studying meant at that time and a kind of social responsibility towards those sectors that were never going to access the university or that would take a long time to do so.

What did this student rebellion demand?

It sought to improve the study plans, expand the possibility of admission for the middle sectors to universities, the possibility of electing authorities -that is to say- the idea of co-government between students, graduates and teachers.

All this is poured into the Liminal Manifesto, which is very Americanist, very Latin American, talking about the struggles of (Emiliano) Zapata and (Pancho) Villa in the Mexican Revolution, about what is happening in the world.

And this has a very strong effect that leads the radical government of (Hipólito) Yrigoyen, we are talking about 1918 and 1919, to begin to apply this in a university law, which effectively established the government of the shared study houses with students and graduates, academic freedom, that is, the possibility that each head of the chair dictates the subject as he sees fit, obviously with certain rules.

And it will significantly expand the access of the middle sectors to the university.

It is the first the first great student rebellion, very innovative worldwide and had its repercussions in Latin America and Europe.

Even when the great rebellion of 1968 took place in Paris, that rebellion that was born in the universities, there is recognition that the 50th anniversary of the rebellion in Córdoba is being fulfilled.

The Liminal Manifesto begins with the phrase “the Argentine youth of Córdoba to the free men of South America.” What is your influence in this region?

It had repercussions throughout the Americas, in Mexico, in Peru, in Cuba.

Even some Latin American parties that will have great political influence in the 20th century -such as the Peruvian APRA- will have a lot to do with the postulates of the Córdoba Liminal Manifesto.

It was a historical element that began to put on the table, particularly in the revolutionary nationalist parties and the progressive parties of Latin America, a list of elementary conditions, because the Manifesto goes beyond university demands, it speaks of changes in society.

And it clearly considers itself Latin American -as when it gives examples such as the Mexican Revolution, nothing more and nothing less than a peasant revolution- which is also a novelty for Argentina, which was a country that had lived looking at Europe.

This Latin American character also surprised the elite itself, and some left-wing intellectuals, who had never taken Latin America as a reference; In any case, they felt they were distant heirs of the French Revolution and of some liberal postulates.

And how did it change Argentina itself?

In Argentina there was a very wide strip of literacy because primary school had reached large sections of the population and this increased the demand for continuity: people wanted to go to secondary school, people wanted to go to university.

This was very important and gave Argentina a very important cultural place within the Latin American context.

It was also a pioneer, because it received enormous support from the labor movement. And the student movement, at the same time, understood that there had to be a connection between the university model and the productive model: society tending towards industrialization, towards the improvement of living conditions.

The Faculty of Medicine in Argentina, for example, with great world-famous doctors, also began to have a social focus from the perspective of the students: medicine as a social element, with some very important doctors like Juan B. Justo , who was the founder of the Socialist Party in Argentina, who spoke of addressing social problems as a preventive element.

It was a revolutionary fact that, a few years later, in 1948, with Peronism, it had the addition of free university studies, which increased enrollment much more, something strange for a third world country.

Today there are more than 60 universities in Argentina that are free and that is very rare in the global context, where university studies are usually very expensive and for few people.

In addition to Latin American students, whose tradition of studies in Argentina can even be traced back to that Córdoba of 1918, in recent years we have had up to 20% of European students coming to Argentine universities. And I’m talking about countries like Germany, Spain, France and Italy that come here in search of academic excellence.

This is good news in the midst of this permanent crisis in which we live, the maintenance of this academic excellence, which often has much more to do with the will of teachers and academic bodies than with governments, because there is always a lack of budget, a lack of resources.

In Latin America we tend to think, when we talk about Argentina, that everything happens in Buenos Aires. Why was the movement born in Córdoba?

Córdoba was the first Argentine university.

Founded by the Jesuits, this university served the needs of the north-central part of the country, which is an immense territory, which included the coastal provinces, the northern provinces and, of course, neighboring countries such as Chile, Bolivia, Peru and others.

Of great academic quality, it had been transformed – and this was one of the points of the students in 1918 – into a very conservative center, with a strong presence of the church, with very reactionary study programs.

Then there was an enrollment that was growing, but with a strong discontent of the students around what was being taught in that university, an aristocratic system of inheritance of chairs and against all that was the reform.

That is why, among many things, the academic contests and the change in the study plans were established.

Source: Elcomercio

I am Jack Morton and I work in 24 News Recorder. I mostly cover world news and I have also authored 24 news recorder. I find this work highly interesting and it allows me to keep up with current events happening around the world.

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/GE4DCMZNGEZC2MJVKQYDAORRHA.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/BUNML4TQNVHSBOBMY5FC3QEM2M.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/FGNDNEX4V5AKXF6INLTN4FLZUQ.jpg)