In January 1913, a man whose passport bore the name Stavros Papadopoulos disembarked from the Krakow train at the North Terminal station in vienna.

Dark complexioned, he sported a large peasant mustache and carried a very basic wooden suitcase.

“He was sitting at the table -wrote the person he was going to meet with, years later- when the door opened with a bang and an unknown man entered.

“He was short…slender…his gray-brown skin covered in pockmarks…I saw nothing in his eyes that resembled sympathy.”

The author of these lines was a dissident Russian intellectual, director of a radical newspaper called Pravda (Truth). his name was Leon Trotsky.

The man you described was not named Papadopoulos.

He was born Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili, known to his friends as Koba, and is now remembered as Joseph Stalin.

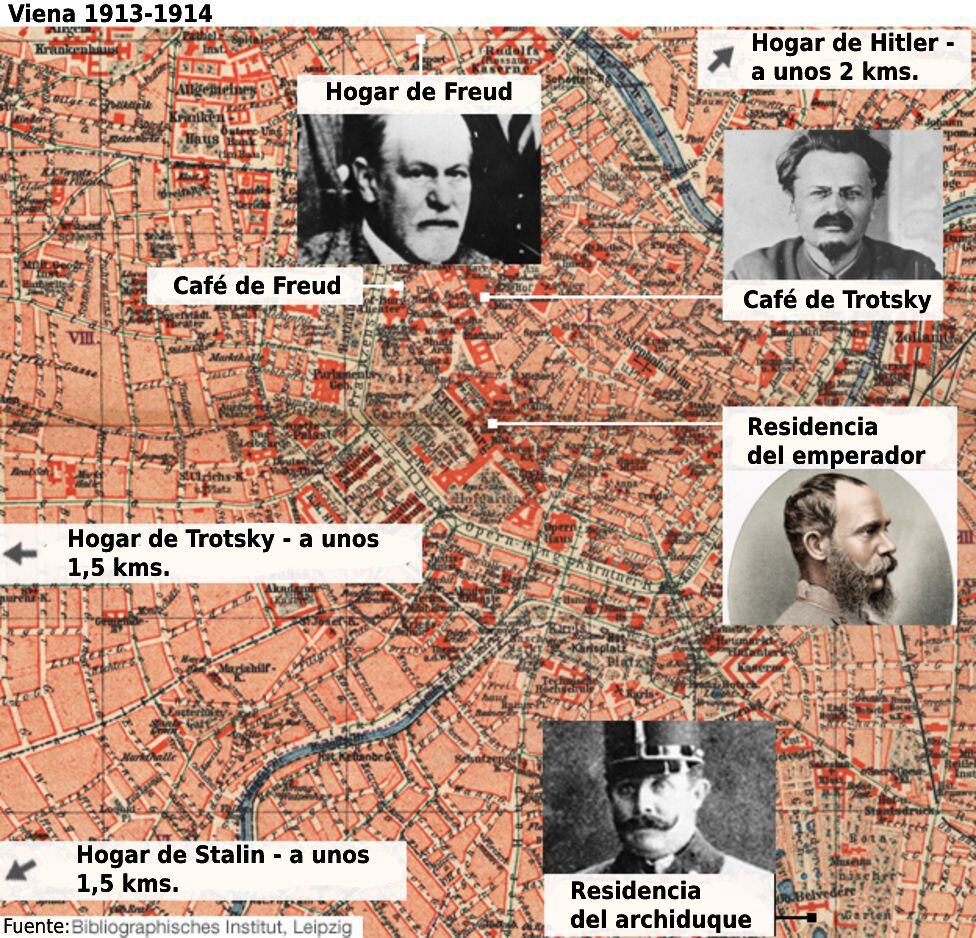

Trotsky and Stalin were just two of a series of men living in central Vienna in 1913 whose lives were destined to shape much of the 20th century.

110 years ago, Adolf Hitler, Joseph Tito and Sigmund Freud were also in the city.

more characters

It was a disparate group.

The two revolutionaries, Stalin and Trotsky, were on the run. Others had different motivations.

Then, Sigmund Freud it was already well established.

The psychoanalyst, extolled by his followers as the person who unlocked the secrets of the mind, was a famous and respected man who had become a doctor in 1881 and established his clinical practice in Vienna in 1886, on Berggasse street.

In 1913 he published the book “Totem and taboo. Some concordances in the mental life of savages and neurotics”.

The young Josip Broz, for his part, who would later achieve fame as the leader of Yugoslavia, Marshal Titusworked at the Daimler car factory in Wiener Neustadt, a city south of Vienna, and was looking for work, money and fun.

Then there was another young man, a 24-year-old from northwestern Austria, whose dream of studying painting at the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts had been thwarted twice after failing the entrance exam and who was now staying at an inn on Meldermannstrasse. , near the Danube.

Was a certain Adolf Hitler.

With a friend, he earned money by drawing postcards of Vienna’s famous sights and then selling them to tourists.

In its majestic evocation of the city at the time, “Thunder at Twilight(Thunder at Twilight), Austrian author Frederic Morton imagined Hitler indoctrinating his roommates “about morality, racial purity, the German mission and Slavic treason, the Jews, Jesuits, and Freemasons.”

“Her hair was tossing, her hands stained [de pintura] they rent the air, his voice rising to an operatic pitch.

“Then, as suddenly as it had begun, it would stop. It would gather its things with an imperious noise, [y] He was walking towards his cubicle.”

Coincidentally, the mayor of Vienna in those years, Karl Lueger, is considered the father of modern political anti-Semitism.

The languages

The city in 1913 was the capital of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which consisted of 15 nations and more than 50 million inhabitants.

“Although not exactly a melting pot, Vienna was a cultural cauldron that attracted ambitious people from all over the Empire“writer and editor Dardis McNamee told the BBC.

“Less than half of the city’s two million residents were natives and around a quarter came from Bohemia (now the western Czech Republic) and Moravia (now the eastern Czech Republic), so the Czech was spoken alongside German in many places.

The empire’s subjects spoke a dozen languages, he explains.

“Officers of the Austro-Hungarian army they had to be able to give orders in 11 languages besides Germaneach of which had an official translation of the National Anthem”.

And this unique blend created its own cultural phenomenon: the viennese coffee.

The coffees

The legend has its genesis in the coffee sacks left behind by the Ottoman army after the failed Turkish siege of 1683.

“Coffee culture and the notion of debate and discussion in cafes is a very important part of Viennese life now and it was then,” Charles Emmerson, author of “1913: In Search of the World Before the Great War.”

“The Viennese intellectual community was actually small and everyone knew each other and that provided for exchanges across cultural borders.”

That atmosphere, he added, favored political dissidents and fugitives.

“There was no tremendously powerful central state. If you wanted to find a place to hide out in Europe where you could meet lots of other interesting people, Vienna was a good place to do it.”

Freud’s favorite hangout, Café Landtmann, still stands in the ringthe renowned boulevard that surrounds the historic Innere Stadt from the city.

But he also frequented the Café Central, a few minutes’ walk away, where cakes, newspapers, chess and, above all, chatting were the passions of the customers.

Among them, Trotsky, Lenin and Hitler.

A famous anecdote relates that Count Berchtold – at the time the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Austria-Hungary -, in the midst of a heated dispute with a local politician who argued that a war would provoke a revolution in Russia, replied with disdain:

“And who will lead such a revolution? Perhaps Mr. Bronstein [Trotsky] from Cafe Central?”.

“Part of what made the cafes so important was that ‘everyone’ wentMacNamee noted.

“So there was cross-fertilization between disciplines and interests.

“Indeed, the boundaries that later became so rigid in Western thought were very fluid.”

In addition, he stressed, “the surge of energy from the Jewish intelligentsia and the new industrial class had made it possible for Franz Joseph to grant them full citizenship rights in 1867 and full access to schools and universities.”

That without forgetting artists, like Gustav Klimtwho in 1913 painted one of his last pictures, “The Young Woman” or “The Virgin” and caused great controversy with a series of erotic drawings exhibited at the International Exhibition of Prints and Drawings in Vienna.

That same year his disciple, the Austrian painter and engraver Egon Schielegave the world several of his most popular paintings, such as “Friendship” and “Woman in Black Stockings”, and wrote to the collector Franz Hauer:

“Just painting is not enough for me; I know that one can use colors to establish qualities. When one sees an autumnal tree in summer, it is an intense experience that involves the whole heart and being; I would like to paint that melancholy.”

And, while it was still a largely male-dominated society, a number of women also made a big impact, notably the composer, author, publisher Alma Mahler.

In 1913, she began her tumultuous and passionate relationship with the Austrian artist, poet, and playwright Oskar Kokoschkawhich would inspire both of them to create great works of art.

But while the city was, and still is, synonymous with music, lavish dancing, and waltzes, its dark side was especially bleak.

A large number of its citizens lived in slums and in 1913 almost 1,500 Viennese committed suicide.

No one knows if Hitler met Trotsky or if Tito met Stalin.

But the situation inspired plays like the 2007 radio play “Dr Freud will see you, Mr. Hitler,” by Laurence Marks and Maurice Gran, in which they imagine such encounters.

the great war

Presiding over it all, in the city’s labyrinthine Hofburg Palace, was Emperor Franz Joseph I83 years old, who had reigned since 1848, the great year of the revolutions.

Archduke Franz Ferdinandhis designated successor, resided in the nearby Belvedere Palace, eagerly awaiting the throne.

His wish to marry Countess Sophie Chotek, a lady-in-waiting to the Archduchess, caused a great deal of controversy.

As heir to the Empire, he was asked to marry into a European royal family but, deeply in love, he refused, marrying Sophie in 1900 after agreeing that their children would not be able to rule.

The archduke saw the weakness of his father’s empire and tried to combat it by strengthening the army and navy.

In 1913 he became inspector general of the army, at the same time that a group in Serbia, the Black Hand, began to hatch a plan against him.

His assassination on June 28, 1914 would trigger World War I.

The conflagration destroyed much of the intellectual life of Vienna.

The empire imploded in 1918, propelling Hitler, Stalin, Trotsky and Tito into careers that would mark world history forever..

Source: Elcomercio

I am Jack Morton and I work in 24 News Recorder. I mostly cover world news and I have also authored 24 news recorder. I find this work highly interesting and it allows me to keep up with current events happening around the world.

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/GE4DCMJNGAYS2MBXKQYDAORRHA.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/F5GGAYKOHBEULGQLSMJ7KSKIBI.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/QAZ5F4UPMBFN7GNVL4JQIJIEIM.jpg)