:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/GE3DCMZNGAZC2MRQKQYDAORRGY.jpg)

Buenos Aires inaugurated it in 1913, Mexico City in 1967, Caracas in 1970, Sao Paulo in 1974, Santiago de Chile in 1975, Rio de Janeiro in 1979, Lima in 2011 and Quito in 2022.

Many large cities in Latin America have metro, less Bogota.

LOOK: The unfair conviction of Edith Thompson, the woman who was executed for the murder of her husband committed by her lover

And when it seemed that the first line would finally be done (in fact, it is already under construction), a new discussion between politicians took the people of Bogotá back in time.

81 years have passed since the first studies of a subway for the Colombian capital were made. It is the largest lag in the region. Because 23 years have passed in Buenos Aires, 9 in Mexico City, 21 in Caracas and Lima, and 20 in Rio de Janeiro between the presentation of the first study and the inauguration.

The Bogota thing is, to say the least, peculiar. AND what happens now serves to understand what has happened before.

Metro line 1 was decided and contracted by the mayor Enrique Penalosa in 2016. It was an elevated system. Her successor and now mayor, claudia lopezHe continued with that plan and started the task despite being contradictory to the ball.

Now that the work is 18% complete, the new president, Gustavo Petro —former mayor of the capital, old enemy of Peñalosa and critic of the elevated—, decided to intervene and speak with the contracted Chinese company to see if his old desire, to make it underground , its viable.

70% of the resources allocated to the metro come from the national budget. The rest are resources from Bogotá.

The discussion between elevated and underground has many edges and arguments. The people of Bogotá —that small urban planner that many here seem to have within— state them these days: Petro affirms that a high rise damages heritage and fosters insecurity; the opposition alleges that it is more expensive and that changing the contract affects the price and the times.

The debate has increased uncertainty. And that has effects, not only on the construction, but on the terms and terms of the loans to finance the works. Failure to comply with the guidelines with the Chinese, on top of that, can have legal and economic consequences.

To increase the uncertainty, This year there are regional elections in Colombia. And the capital, with its huge electorate and political influence, is the most desirable place. The debate on the metro takes place in an electoral key.

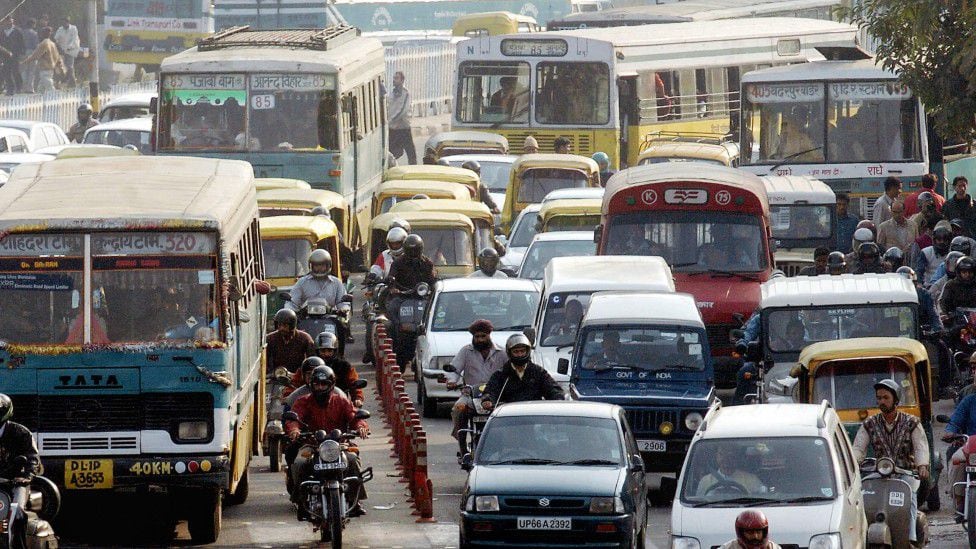

Meanwhile, this metropolis of 10 million inhabitants continues to lead international rankings of the worst traffic in the world.

What is it, then, that has prevented Bogotá from having a metro for 81 years?

“Increasingly expensive and unfeasible”

When the first project was carried out, in 1942, Bogotá had 400,000 inhabitants, an efficient tramway system, and an average population density.

But then the governments, locked in a partisan struggle, modified the urban development plan several times and, with clientelistic rather than urbanistic purposes, changed the tram for buses. The city, at the time, received millions of people displaced by violence, becoming one of the most densely populated in the world.

Bogotá is today a particularly segregated city, where, in general terms, the rich live in the north and the poor in the south. Most people live far from most jobs. Millions must commute three to four hours a day to get to work.

As the population and labor densities generated a urban traffic jamthe discussion about the subway became politicized, becoming a symbol of high sensitivity.

“Having made the decision in 1942 it would have been much easier than it is now,” says Oscar Alfonso Roa, an urban economist. “Because before there were no institutional intricacies, nor socio-spatial segregation, nor the commercial and financial complexity of today (…) Delaying the decision has only made the project more expensive and more unfeasible“.

In these eight decades the State has commissioned at least three studies to government entities and seven to private companies abroad. They all raised different systems and budgets. They all created a hope that did not generate works, but costs for non-compliance.

The background that complicated things

Experts agree that the Bogotá metro was never as close to being built as it was in the 1990s, when there was consensus on a system and a form of financing.

But three things happened: the country entered a severe economic crisis, an earthquake in the Coffee Zone diverted the efforts of the State and the Medellín metro, which managed to inaugurate in 1995 after 10 years of obstacles, cost double what was budgeted.

“The Medellín metro spent more money than it should have and from that moment on a Metro Law was created that imposed many restrictions to do so,” says Valentina Montoya, a lawyer and mobility expert.

“In the midst of the crisis and with that law it was easier to make the Transmilenio, which was cheaper and did not demand as many requirements,” he adds.

At the time, Enrique Peñalosa, an outspoken skeptic of the metro and a staunch defender of rapid transit buses like the Transmilenio, was managing his first term as Bogotá mayor (1998-2001).

The red buses of the Transmi, as they are known here, took over the city.

The old problem of autonomy

Throughout its republican history, Colombia has tried to organize —for many without success— the enormous diversity of its territory. The discussion between the need for a federalist or centralist State was not settled with the civil wars of the 19th century or with the Constitution signed in 1991, which wanted to give autonomy to the regions.

“After the Constitution we were left with a lot of municipal autonomy, but little budget for large works“, says Darío Hidalgo, a doctor in transportation engineering.

If Bogotá wants a metro, it depends on the nation. And only on rare occasions, such as in the 1990s, have the two governments been aligned.

Now, with Petro and López in power, interests have been diverted and, as has happened before, there are elections on the horizon.

“The windows between the election of president and mayor are very short (an average of two years, without immediate re-election) to agree and move forward,” says Hidalgo. “Every mayor and president wants to put their stamp on it and claim the credit.”

Hidalgo remembers the metaphor that the former mayor of Bogotá used to explain all this Antanas Mockusa pioneering mathematician and philosopher in citizen culture policies: “The biggest fear of a Latin American macho —he used to say— is raising other people’s children, and we need the opposite: people who can raise the children of anotheryes”.

The mayor’s office of Bogotá is considered the second most important post in the country. It has been a springboard for two presidents and four presidential candidates in the last 30 years.

Getting the capital’s most emblematic infrastructure work finally done is the goal of anyone seeking power in Colombia. That’s why everyone tries to get credit from her.

institutional twists and turns

In addition to its centralist tradition, Colombia has an old link with the law. The Justice Studies Center of the Americas reports that no country, only Costa Rica, has as many lawyers as this one. Few judicial systems have as many high courts as this one: eight.

In a legal country, Colombians signed a guaranteed Constitution in 1991. The text, perhaps unintentionally, generated a fragmented State, full of small entities with power, with few officials and dependent on laws and resolutions that make them inflexible.

And that, the experts point out, has made it difficult to build the subway, especially after a corruption scandal that brought down the mayor of Bogotá in 2011. Any studio can be sued; every project must go through umpteenth oversight filters. Legal and administrative byways that the opposition uses, legitimately and legally, to hinder the management of whoever governs.

Valentina Pellegrino, an anthropologist who has studied Colombian institutions, says: “The Constitution of 1991 generated a new idea of State and accountability that created all these instances of oversight.”

In terms of transportation, only in Bogota there are at least nine entities that exercise control in a relatively autonomous way. Its articulation is subject to particular logics of power and budget. Coordinating that is, as the Colombians say, a “chicharrón”.

Overdiagnose to run

“We don’t have a metro because Bogotá—and Colombia—is full of cowards,” says Carlos Felipe Pardo, a psychologist who specializes in mobility. “We overcalculate the risks of buying something. That cowardice is complemented by the saddest risk of the possibility of corruption, and the fear of cost overruns.”

There have been politicians who have not wanted to make the decision of the metro. Others who have wanted to hinder the decision of those who made it.

And given the lack of results —says Pellegrino— studies, demands and resolutions: “It is as if the important thing was to make the recipe, not the food (…) In Colombia you demand results and the State gives you studies and documents“.

In many instances of the Colombian State, problems are overdiagnosed as a way to solve them, says Pellegrino, based on academic studies.

“And that is also what happens with the Bogotá metro, with the difference that it has been more visible here, because we have all seen this fight between the studios of one and the studios of the other.”

Studies, resolutions and demands that serve those who do not want to raise other people’s children.

Source: Elcomercio

I am Jack Morton and I work in 24 News Recorder. I mostly cover world news and I have also authored 24 news recorder. I find this work highly interesting and it allows me to keep up with current events happening around the world.