“The state of the work, when I saw it for the first time, could not be believed. You couldn’t see the original paint, it was completely covered by plaster and more paint. It had five or six layers on top. I had to ask myself if he was a Leonardo or not, because he was completely unrecognizable.”

This was the reaction of Pinin Brambilla, one of the world’s greatest authorities on the conservation of Renaissance frescoes, when he came face to face with “The Last Supper”.

LOOK: “I was sexually abused, like so many other autistic women”

It was 1977 and Brambilla, who passed away at the age of 95 in 2020, had taken on the challenge of restoring Da Vinci’s great work commissioned by the Duke of Milan Ludovico Sforza more than 500 years ago.

She was not the first to try to save this imposing 4 and a half meter high mural that decorates a wall of the refectory of the monastery of the Church of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan.

Others before her had tried unsuccessfully to rescue this doomed work, and these efforts had culminated in resounding failure.

Since Leonardo finished the work in 1498, “six restorers worked on the painting. And each one of them changed the physiognomy, the characteristics and the expressions of the apostles,” Brambilla told BBC journalist Mike Lanchin, when interviewed on 2016.

Mateo, for example, was a young man, but successive attempts to stop the deterioration of the mural had turned him into “an older man, with dark hair and a small neck.”

Christ, although he was not so changed, “had lost part of his humanity, of his beauty,” said Brambilla.

“What we sought with our restoration was to recover the character of each individual. And that was very exciting,” he explained.

short-lived technique

And it is that the big problem with the mural – which captures the drama of the Jewish Passover dinner and the moment in which Jesus reveals to his disciples that one of them is going to betray him – is that it began to disintegrate almost as soon as it was finished.

Due to his well-known perfectionism, Leonardo dismissed the traditional technique of al fresco painting, in which the artist applies paint to a layer of still-wet lime mortar.

This methodology makes the pigment stick to the wall, but requires quick work to finish the strokes before the wall dries.

To avoid rushing and spend time on every detail, Leonardo decided to apply a experimental technique which consisted of painting with tempera or oil on a surface of dry plaster

This meant that the pigments were not permanently attached to the wall. And over time -which at first seemed to have played in the artist’s favor- the image began to flake off.

Cumulative damages and fixes

Several factors contributed to the deterioration of the Cenacle (as the work is also known).

To begin with, the wall of the refectory where the mural is painted absorbed the humidity of an underground stream that ran under the monastery, a detail that Leonardo was unaware of. Also given its location, it was receiving waves of smoke and steam emanating from the kitchen.

Years later, Napoleon’s army used the building as a stable and more recently, during World War II, an Allied bomb fell on the convent.

Although the wall remained standing, it was left exposed to the elements.

However, the most worrying thing for Brambilla was not what time and bad weather had done to the work, but rather the unfortunate conservation efforts that had been made to save it.

“The first thing I looked at is what happened in the years since Leonardo painted it. Which restorers did what things, how they worked and what materials they used,” Brambilla told the BBC.

Let’s do it

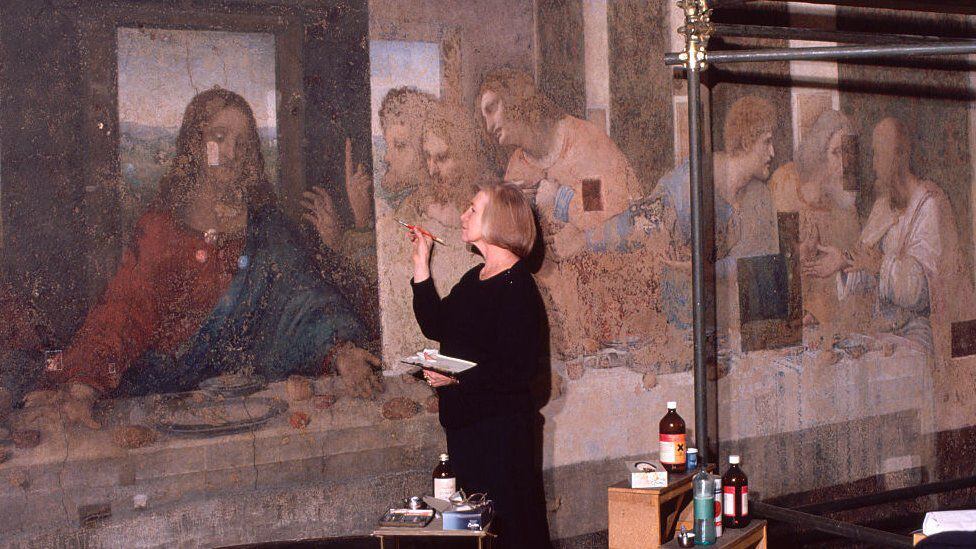

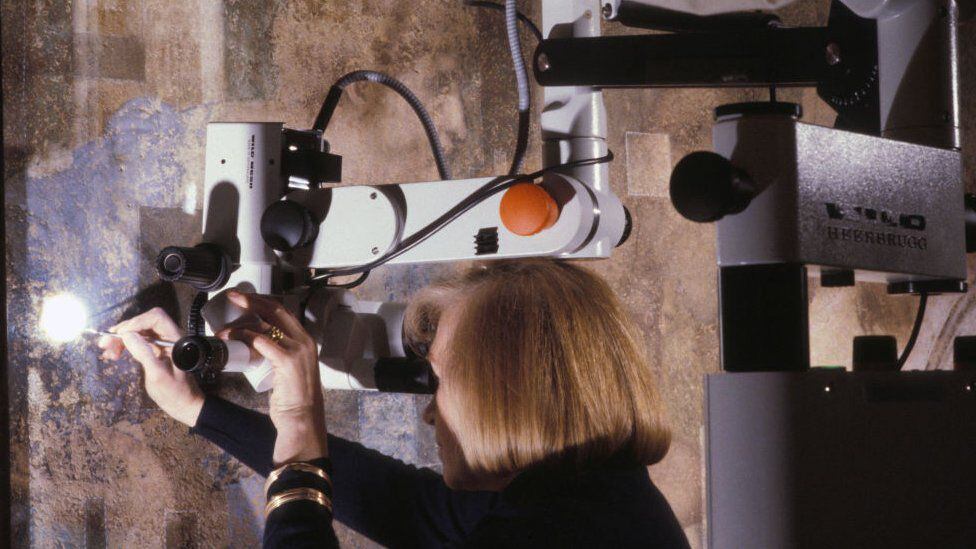

After initially sealing the room to keep out more dust and dirt, and erecting massive scaffolding in front of the fresco, the restorer and a small group of assistants drilled tiny holes in the wall to insert tiny cameras to establish how many layers of paint were covered. the original work.

“We worked with small fragments at a time, with great difficulty, because the painting below (Leonardo’s) was very fragile, while the one above it was very robust,” Brambilla explained, making a gesture with his hands that reveals that the size of these fragments did not exceed 5 x 5 cm.

Laboriously, with the help of magnifying glasses, surgical instruments, and tons of patience, the team peeled away layers of paint and glue to reveal the original colors of the work, while leaving other parts bare, barely touched up with watercolors.

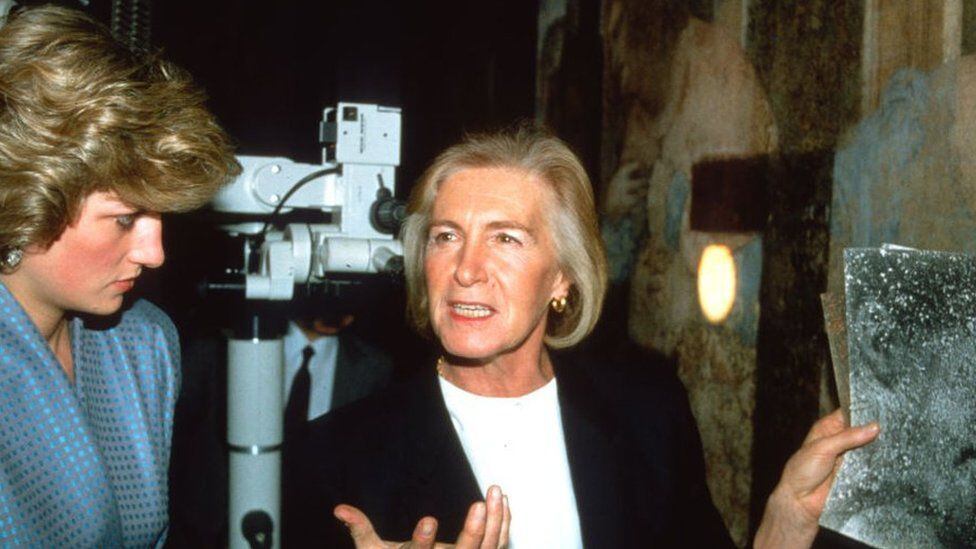

Finishing each section took months, years. Multiple interruptions also affected the continuity of the work: from technical and bureaucratic difficulties to visits from foreign dignitaries and European royalty.

Finished homework

Brambilla’s dedication also impacted his life and his family relationships.

“Work made me spend a lot of time away from my husband and my son. Sometimes I worked alone, even Saturdays and Sundays until noon. At one point my husband told me ‘enough’, this is enough for The Last Supper, I want to live a little.’ But I was totally obsessedBrambilla recalled.

Until finally in 1999, after little more than two decades, when the expert was already over 70 years old, she considered the task finished.

By removing centuries of dubious restorations, lines that were crude and inexpressive became delicate, refined. Now you could clearly see the food on the table, the doubles on the tablecloth.

Some critics believe that the restoration took too much paint off the work, others say that it is almost as it was when Leonardo finished it.

Brambilla was satisfied with her work, but she confessed the sadness she felt when the process was finished.

“When I finished working on the painting, I was sad because I had to leave it,” he said, acknowledging that it is something that happened to him not only with Leonardo.

“For each work that I restore, a part stays with me, something from the artist. Distancing myself is always difficult. It’s like you lose a part of you.”

Source: Elcomercio

I am Jack Morton and I work in 24 News Recorder. I mostly cover world news and I have also authored 24 news recorder. I find this work highly interesting and it allows me to keep up with current events happening around the world.

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/GE3DCMBNGA2C2MBWKQYDAORRGY.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/GE3DAMBNGAZC2MJQKQYDAORRGY.jpg)