When World War II ended, United Kingdomwhich had suffered massive destruction due to Nazi air raids – known as the Blitz – undertook a gigantic campaign of reconstruction.

To do this, it turned to its colonies, grouped in the Commonwealth of Nations (“Commonwealth”), offering employment and a new life in the United Kingdom to those who were willing to join the reconstruction efforts.

LOOK: The key role of slaves and concubines in the “bloody world of succession” of the Ottoman Empire

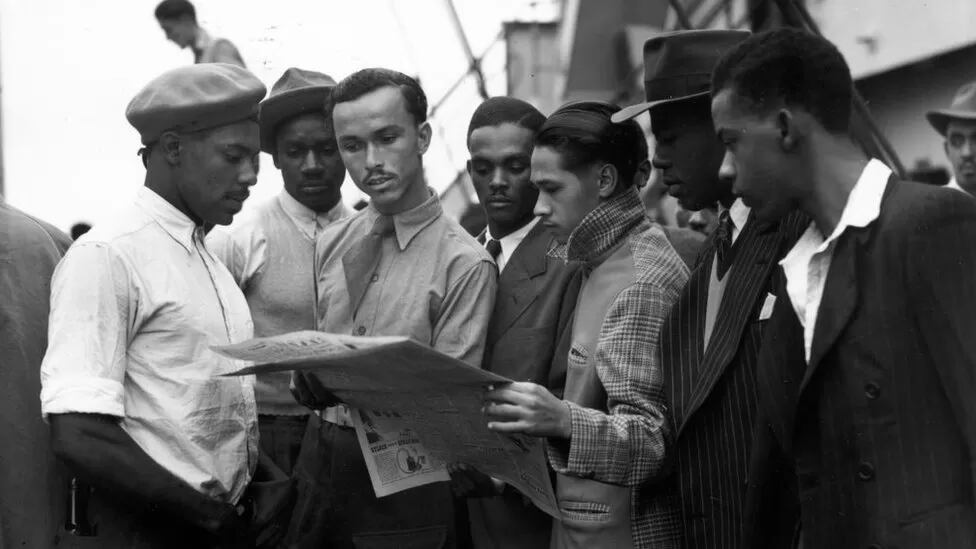

Between 1950 and 1970 thousands of citizens of Caribbean countries like Jamaica, Barbados, Guyana or Trinidad and Tobago —which then remained under British rule— responded to the call and moved to the British Isles, many with their families.

That generation was nicknamed windrushthe name of one of the first ships that arrived from the Caribbean with these young migrants.

Most never comeback to their countries of origin.

The Windrush generation left a strong mark on the UK and, since 1966, Caribbean culture has been celebrated every year at the famous Notting Hill Carnival, one of London’s most popular festivities.

However, in recent years these post-war Caribbean immigrants have been at the center of a number of controversies.

In 2018, British Home Secretary Amber Rudd was forced to resign after it was discovered that some members of the Windrush generation had been declared illegal immigrants.

The scandal came to light after the leak of documents showing that Theresa May’s Conservative government had set deportation quotas for immigrants, including people of Caribbean origin who had arrived in the postwar period to help with reconstruction efforts.

Now, a BBC investigation has uncovered a new controversy related to the Windrush generation.

deported sick

Declassified documents revealed that hundreds of these immigrants who suffered chronic illnesses or mental health were sent back to the Caribbean, something that has been described by the current British government as a “historic injustice”.

Documents from the National Archives discovered by BBC News’ Navtej Johal and Joanna Hall show that at least 411 people were sent back between 1958 and the early 1970s, under a scheme that was supposed to be voluntary.

Since government departments at the time do not appear to have kept complete records, it is estimated that the number could be higher.

Some experts believe that the scheme may have been illegal because not all of the patients had the mental capacity to agree to leave.

Relatives of those who left are demanding that the government open a public inquiry into this controversial repatriation policy.

A spokesman for Rishi Sunak’s Conservative government said: “We acknowledge the campaign by families seeking to address the historical injustice their loved ones face, and we remain utterly committed to righting the injustices facing members of the Windrush generation.”

Families “torn apart”

Journalists Navtej Johal and Joanna Hall they contacted some of the children of returnees, who revealed how this policy “ripped apart” their families.

He June Armatrading’s father, JosephHe came to the UK in 1954 and lived in Nottingham with his wife and five daughters.

He came from St Kitts, a British colony still administered directly from London, and therefore held a British passport.

In the 1960s he began to struggle with his mental health and was diagnosed with paranoid psychosis. In 1966 he was returned to St Kitts. He never saw his family again.

June, now 65, said her mother told her and her sisters that their father had “abandoned” them.

She grew up always believing that her father did not love them, which caused her “great anguish”.

However, among the documents seen by the BBC was a letter written by Joseph in which He was asking to return to the UK so he could be reunited with his family.. Little is known about what happened to him next.

In other previously confidential documents, government officials admitted that Armatrading’s repatriation procedure had “not been correct” and that he had been mistakenly stripped of his passport.

When BBC News journalists showed June the letters, she was shocked.

“I’m upset. It’s terrible, really terrible…how dare you?” she said. “He was a vulnerable man. You’re supposed to take care of your vulnerable people and they didn’t. They just left him, They abandoned“.

Marcia Fenton she was put in an orphanage when she was little.

His mother, Sylvia Calvert, had been sent back to Jamaica in the late 1960s, and his father couldn’t manage on his own.

Mother and daughter only met again many years later in Jamaica. Sylvia had already been discharged, but she was still not feeling well. She died in 2007.

Marcia still wants to know what happened to her mother when she returned to Jamaica. All she knows is that she spent some time at Bellevue Hospital, in the island’s capital, Kingston.

“The fact that they sent her back to Jamaica deprived me of having a mother“Marcia told the BBC.

He wants an investigation into how and why people like his mother were returned. “No one should have been repatriated if they had a mental illness,” she said. “The British government should apologize“.

According to the policy carried out by the National Assistance Board -precursor of the current Department of Work and Pensions-, which was in charge of the process, only those people who they had “expressed their desire to return”.

But Professor Kris Gledhill, who previously served as a tribunal judge in mental health cases, said it was questionable whether the practice of repatriating mentally ill patients was legal.

“What you’re doing is relying on a ‘voluntary choice’ that, if you were to properly assess the person’s ability to make that choice, you would say that does not have capacity“.

The declassified documents also suggest that the repatriation should only take place if it “benefited” the patients and if there were “adequate arrangements” for their return.

However, academic research on the state of mental health care in the Caribbean at that time points out that it lacked “trained personnel and resources.”

Documents from the time show that British government officials were concerned not to give the impression that they were “actively trying to get rid of… Commonwealth citizens of no use to Britain”, but this does not appear to have been the case. convinced Jamaican officials.

In 1963, the High Commissioner’s Office wrote to the British government complaining that UK hospitals were requesting repatriations “largely because of pressure on beds or other hospital services”.

“Colored Immigration”

As “citizens of the United Kingdom and Colonies” (CUKC), the Windrush generation enjoyed the same legal status than anyone born in the UK. However, Professor James Hampshire of the University of Sussex said that since the first arrival of people from the Caribbean Commonwealth, both Labor and Conservative governments they wished to restrict their number.

“The intent and effect of legislation that was passed in that period [décadas de 1960 y 1970] was to restrict some types of migration and not others. It was primarily directed at what was called ‘immigration of color’ at the time,” he noted.

For her part, immigration attorney Jacqueline McKenzie of the Leigh Day law firm, who represented hundreds of victims of the 2018 Windrush scandal, said “lives have been destroyed.”

“The State must now provide the descendants of these people with answers and some kind of reparation,” he said.

Drafting

BBC News World

Source: Elcomercio

I am Jack Morton and I work in 24 News Recorder. I mostly cover world news and I have also authored 24 news recorder. I find this work highly interesting and it allows me to keep up with current events happening around the world.

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/FV2C7WPIFNBG7ELRBKUFJD44PU.png)