With the profanity of “Kiss my ****!”, an American ignited a riot that became a turning point in American history. Panama.

Such an American was one of the so-called filibustersthose men capable of doing dirty jobs in order to get wealth, be it with the gold rush in the western United States or also in foreign territories of the Caribbean and Central America.

LOOK: Oppenheimer and Einstein: the complicated relationship between the “father” of the atomic bomb and the Nobel Prize in Physics

They left from cities like New York or Boston together with immigrants who traveled to the Panamanian isthmus -which was then part of New Grenada– on a journey of thousands of kilometers to California.

On the street of La Ciénega, in the still rural city of Panama, the filibuster jack oliver on April 15, 1856, insulted José Manuel Luna, a watermelon vendor.

“Be careful, we are not here in the United States”The Panamanian responded to Oliver’s easy insult, who refused to pay 1 real (about 5 US cents) for the slice of watermelon he had eaten.

But what could have been an irrelevant street clash was actually a reflection of a boiling social situation.

“It should be understood that the deeper meaning of the watermelon slice incident It is the manifestation of a first movement to dignify a humiliated people. That is the most important thing,” explains Dr. Hermann Güendel, a specialist in Latin American studies at the National University of Costa Rica and author of analysis of the subject, to BBC Mundo.

The revolt it sparked lasted three days, resulting in the deaths of 16 Americans and two Panamanians, as well as a couple dozen wounded on both sides.

But since then, the so-called “watermelon slice incident” was capitalized by Washington to initiate an occupation of the strategic passage between the Pacific and the Atlantic in the future Panama Canal.

What happened before the incident?

Since the 1840s, the United States had a strategic presence on the Isthmus of Panama, where the Chagas River was the key passage to cross from the Pacific to the Atlantic without the need to skirt the entire continent.

The US signed with Nueva Granda (which included Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador and Panama) the Mallarino–Bidlack Treaty in 1846 with which it assured its citizens and economic interests a privileged treatment in the passage through the isthmus.

“In principle, this seemed to the Panamanian population at that time a golden opportunity for economic growth. They expected transportation, lodging, food. But the fact was quickly that was left in the hands of the same Americans”, explains Güendel.

The company’s train route Panama Canal Railway it replaced the trips in Panamanian boats. The hostels and dining rooms that were opening in the towns of Colón and Panamá were also staying in the hands of the Americans.

And beyond that, the Panamanians began to see pushy attitudes of the Americans, who used the treaty of 1846 to act with many liberties: “USA. It was already developing in the philosophy of Manifest Destiny, by which those in charge of bringing civilization to America are considered”, says Güendel.

“When they arrive American immigrants bring that worldviewfrom Latin America, and this led them to an arrogant and mocking treatment of the population, its laws and the authorities of New Granada”, he adds.

How did the altercation take place?

On April 15, 1856, among the American travelers who arrived in Panama was Jack Oliver.

The man was accompanied by other filibusters. It was common for some of these “they took advantage of their short stay to satisfy their vices in gambling dens and taverns”as described by the historian Juan Bautista Sosa in his “Compendium of the history of Panama” (1911).

In an apparent drunken state, Oliver went to José Manuel Luna’s stand and took a piece of watermelon. After half eating it, he threw it on the floor and when he tried to leave, the vendor demanded payment of one real. But Oliver snapped back and held up his gun. Luna took a knife from his stall, Sosa says.

Oliver’s classmate chose to pay for the slice of watermelon, which would have ended the problem. But a man, identified as Miguel Abraham, took advantage of the moment to wrest the gun from Oliverwhich led to a pursuit by the Americans.

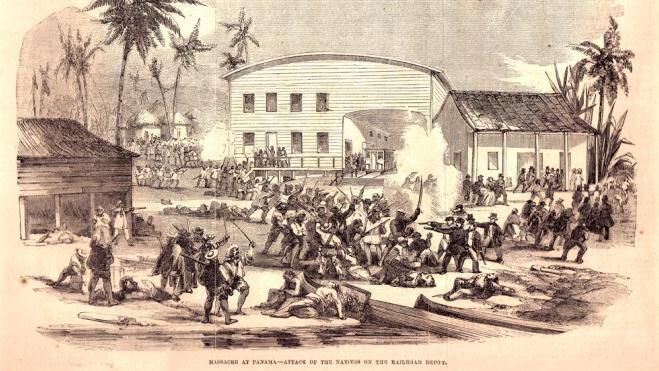

“They chased the kidnapper with shots,” Sosa reports. Realizing this, nearby Panamanians became involved in the defense of Abraham and Luna. Then a brawl broke out between both sides that advanced to the train station, where Oliver entrenched.

Coincidentally, a train with more than 900 passengersbetween men, women and children.

The Panamanian guard went into action by order of Governor Francisco de Fábrega. They opened fire to repel the shots coming from the train station, which was eventually secured. But the altercation resulted in the death of 16 Americans, as well as two Panamaniansin addition to the wounded on both sides.

A slice of almost half a million

Washington did not sit idly by. He instructed diplomat and agent Amos B. Corwine to conduct an investigation into what happened. He submitted a report on July 8, 1856 based on “witness statements to the attack and other collected supporting documents,” as recorded in the US National Archives.

Corwine, however, did not mention that the origin of the incident was Oliver’s wrongdoing. On the contrary, He recommended the military occupation of the strategic points in the passage of the isthmus, both in Colón and in Panama.

“In his report, he points out that it was all because of the brutality of the blacks, regardless of what the British, French and Ecuadorian consuls said, that it was the fault of the American filibusters,” Güendel explains.

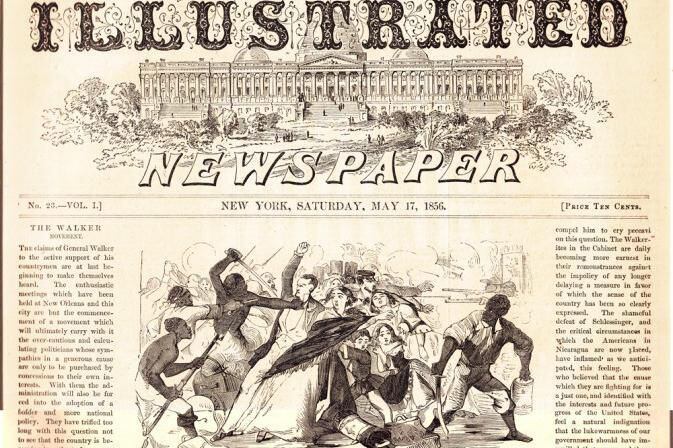

The researcher notes that in the US the incident was reviewed in a derogatory manner, as on the front page of the New York newspaper illustrated that recounted what happened in a very partial way.

“The image proposes to a group of African savages, semi-dressed, with machetes, attacking white knights, Americans, with their families and their children. That is the conception, a relationship with savages, ”she points out.

Two ships and 160 military personnel took control of the territory of New Granada for three days in September 1856, thus giving the first of a dozen US military interventions in Panama.

To settle the differences, the US and Nueva Granda convened a mixed commission to resolve the situation. One of the results was the payment of US$412,349 in gold from Nueva Grandaas well as guarantees on US interests in the isthmus.

“This forces Nueva Granda to declare the autonomy of Panama and Colón in favor of the Americans. And the close to US$400,000, about US$2,000 million now, never reached the families of the dead Americans. The big winner of all this was the United States thanks to the ability to handle this situation,” says Güendel.

Basically, the researcher points out, the agreement between the parties did not resolve a social situation of oppression that had been perceived for years before the incident involving the slice of watermelon.

“The incident was a catharsis for a people who felt humiliated, sullied, as a way of freeing themselves from that feeling to which they were being subjected by the American presence. That is why the incident was a national cause”, affirms the academic.

“And in the end it was also a justification to occupy it militarily and over the years it will consolidate the US presence in the canal and the 5 km on each side of the canal that became US property,” he adds.

Control of the key passage between the Atlantic and the Pacific would last for more than a century and a half, until the last day of 1999.

Source: Elcomercio

I am Jack Morton and I work in 24 News Recorder. I mostly cover world news and I have also authored 24 news recorder. I find this work highly interesting and it allows me to keep up with current events happening around the world.

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/54VI4S4GXBCQLGKPMHSCHO52LM.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/34K4SMDZBBFPLPBWFLVVNLYR44.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/5UDTEDW2RFBPFONK7CKXCRGQB4.jpg)