Johandri Pacheco boarded the train with a stomach ache.

An eight and a half month old belly.

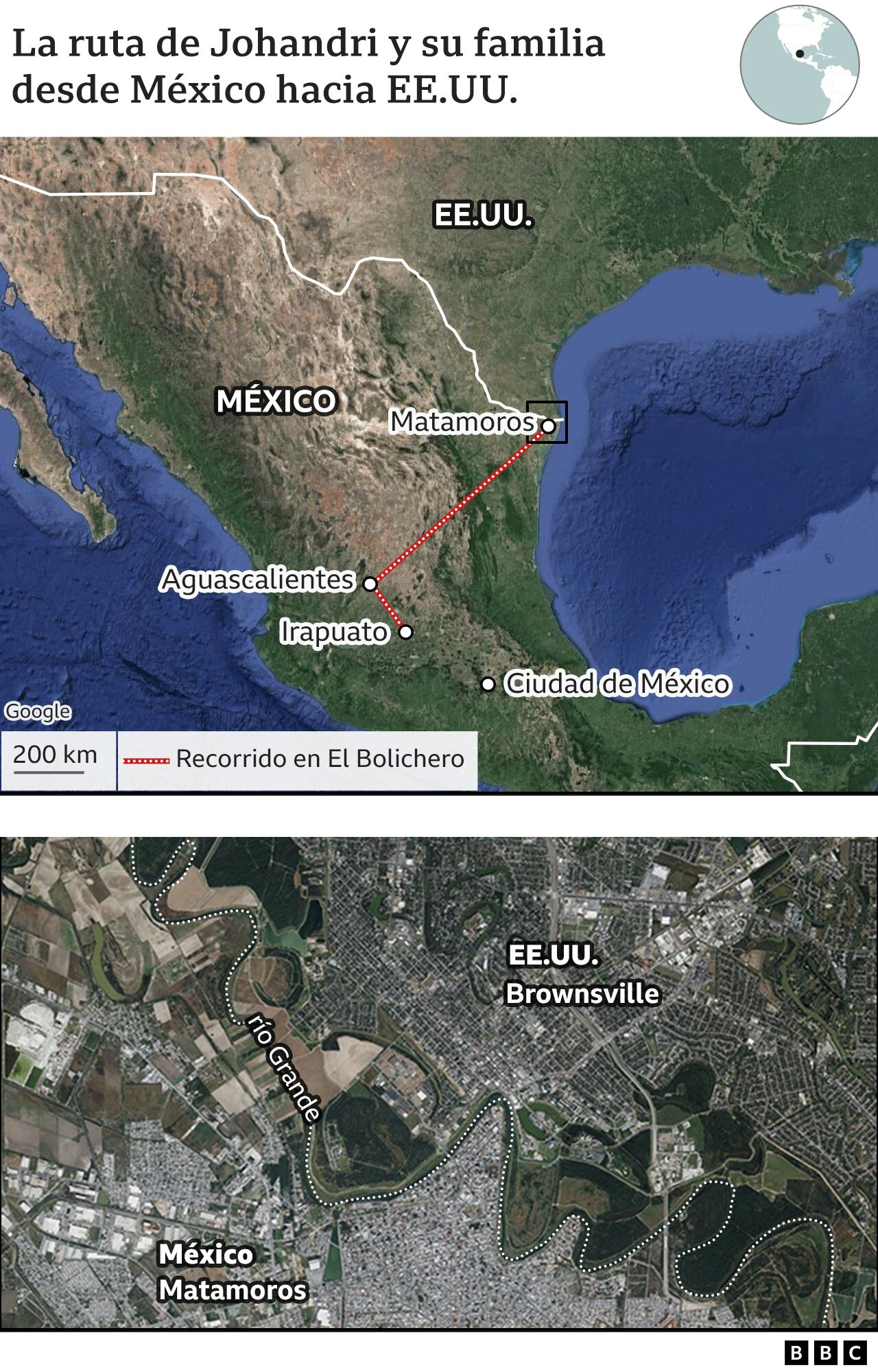

He didn’t enter the car door to sit in a chair and observe the landscape between Irapuato and Matamoros, from central to far eastern Mexico, on the border with the United States.

WATCH: Police chase South America to arrest Niño Guerrero, leader of the Tren de Aragua megagang

He climbed a ladder on the side of the car to the roof of a freight train that belongs to the Mexican railway system, an old railway network known as La Bestia.

The 23-year-old Venezuelan migrant was exhausted. Together with their partner José Gregorio and their 4-year-old son Gael, they waited for the train to arrive on a bridge in Irapuato for five days.

Other migrants said that train was known as El Bolichero, because of the small metal balls that are stored on the roof and that they had to cover with cardboard to rest during the journey.

Johandri and her boyfriend collected cardboard for the trip and ate the food that activists and spontaneous people distributed on the bridge.

The couple and their child traveled to a dozen countries for a month and a half to ensure that Mía, the baby Johandri was carrying, was born in the United States.

“A friend scared me, she told me that if I gave birth in Mexico, they would return me to the border with Guatemala and register my daughter as Guatemalan,” she says from a migrant shelter located in Aguascalientes, in central Mexico. .

“My fear was going to the hospital and being taken back by Immigration.”

The train arrived in Irapuato at midnight on Friday, August 25th. 12 days left until deliveryaccording to the estimate of the doctor who performed the last prenatal care.

“Go to your country”

Johandri grew up in Las Adjuntas, a popular neighborhood southwest of Caracas.

As soon as he turned 18, he emigrated to Peru shortly before the pandemic, without having completed high school or having professional experience. “I wanted to see the world through my own means, achieve my own things through my own efforts.”

The economic crisis, lack of access to public services and violence in Venezuela have driven the migration of more than seven million people since 2015, according to the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR).

Johandri got his first job in Peru as a clerk in a shoe store. “Go to your country, you Venezuelans come and fuck”, some customers told him, according to him. She pretended not to hear and turned away in silence.

“These comments don’t affect me,” he says, remembering the insults he received in that store. “I’m fighting for myself and my family.”

In Peru she gave birth to Gael, her first child.

However, in mid-2021 his future outlook changed. Prices rose and his salary was not enough to pay his rent and food.

With less than US$100 in his pocket, Johandri ruled out the option of returning to the family home in Las Adjuntas and He emigrated to Chile hitchhiking on the roads.

She got a job as a cleaner at a small clinic in Santiago. He sold clothes himself and served drinks in a bar. When she thought she had achieved financial stability, she raised the rent on her new apartment and feared she would be forced to return to Las Adjuntas.

“I decided we should leave Chile when I was seven months pregnant,” to remember.

“With the baby in my belly, I had two arms and two legs to cling to the trees and cross the rivers of the Darién, which was one of the most difficult parts of the trip. But if I carried her in my arms it would be impossible.”

“Everyone wants to steal from you”

The couple had US$700 to make the land trip with Gael to the United States through Chile, Peru, Colombia, Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala and Mexico.

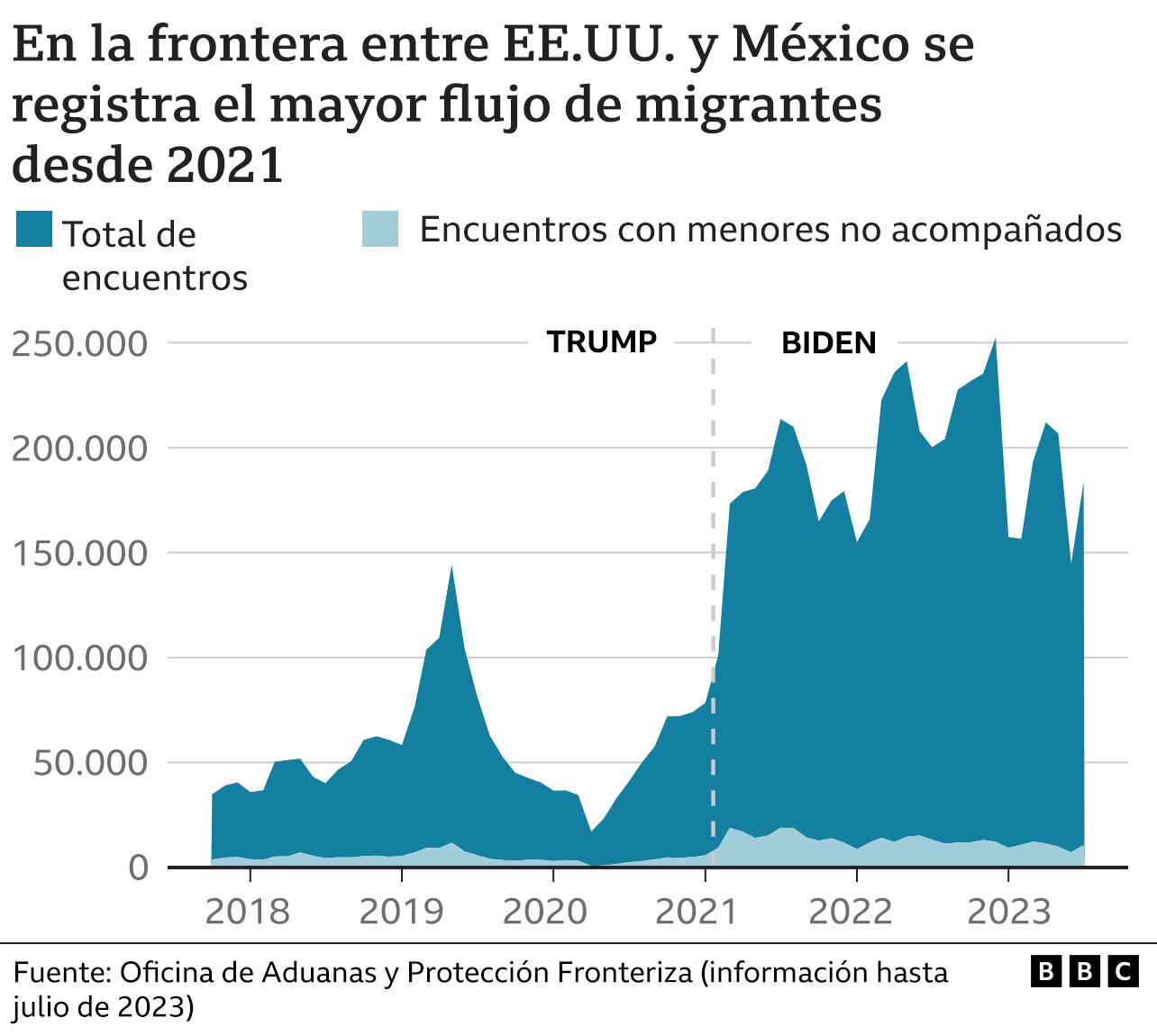

They made the first leg of the bus trip, from Chile to Capurganá, a Colombian city on the border with Panama and one of the main entrances to the country. the Darién Gap, the intricate jungle through which almost 249,000 migrants passed during the first half of 2023the largest migratory flow recorded so far by the Panamanian authorities.

Seeing so many children with fever, vomiting and rashes on the trip through Darien, Johandri was happy to have made the decision to travel pregnant. However, he never thought that the hardest part awaited them in Mexico.

“In Darién you can drink water from the rivers and take refuge in the shade of the trees. But in Mexico we had to walk five or six hours every day in the sun. Everyone wants to steal from you, cheat you. We tried to continue by bus and the police always took us away because we didn’t have documents.”

After traveling for a month and a half, boarding El Bolichero in Irapuato and arriving in Matamoros was the last step to crossing into the United States.

Alert on a cardboard

Johandri and José Gregorio placed the cardboard on the roof of the train and placed Gael between them to sleep.

At 2am, Johandri woke up clutching her stomach to ease the pain.

There were still 12 days until the birth.

When Johandri had her first child, labor contractions were accompanied by back pain. This time only his stomach hurt, so he assumed that those spasms were a product of tiredness and the rigors of the train.

However, the pressure in my belly acquired a rhythm, it hurt from time to time and with increasing intensity. Johandri told his partner to call for help immediately. Mia was on her way.

At 5 am, José Gregório took one of the cardboards they used to sleep and wrote: “A baby is being born. We need the train driver to find out. Urgent”. He asked other migrants to pass the cardboard to the first cars, hoping it would reach the driver’s hands.

“Get ready, my love.”

While some shouted if anyone could help a woman who was giving birth, Johandri and José Gregorio saw a man approaching the roof of the first train carriage.

He was a Venezuelan paramedic who was also trying to reach the United States. The man took out his cell phone and called his wife, a nurse who would explain how to help Johandri during contractions.

“Get ready, my love. Look for alcohol, that’s what you’re going to do…”Johandri remembers the nurse telling her husband over the loudspeaker.

The contractions happened every three minutes, the paramedic estimated. Then every two minutes. Johandri started vomiting, crying without being able to contain it. I didn’t want Mía to be born on that dirty roofabout those metal spheres that overheated in the sun and needed to be covered with cardboard to rest.

They took alcohol, scissors and a blanket so that the baby’s body wouldn’t touch the cardboard. Johandri surrendered to the idea of her daughter being born in Mexico, on the roof of a train car.

The paramedic told José Gregorio to hold Johandri by her back and gently push her upper belly to help the fetus descend.

“He’s not coming on this train.”

At 7 am, lawyer Paola Nadine Cortés, an activist with the Agenda Migrante association, received a photo of the poster that José Gregorio wrote asking for help.

The lawyer called Civil Protection for a group to travel to the Ferromex company yards, in the municipality of San Francisco de Los Romo, 222 kilometers north of Irapuato station.

“The idea was to call an emergency service and rescue her because they were sending me videos and she looked in deplorable conditions.”says the activist.

The train company put Cortés in touch with the driver of the train they assumed Johandri was traveling on.

“I sent him a photo so he could see the train number. Then the driver told me: ‘Don’t come on this train. It’s the one that goes the furthest.’”

This driver contacted his colleague and they agreed to stop the train for ten minutes in the city of Aguascalientes.

“The driver told me it was ten minutes counted by a clock. If they were unable to remove it within that period, the train would continue on its journey”, says Cortés.

The train stopped in the Los Arellanos community, about 108 kilometers from the city of Aguascalientes.

“Due to the distance and centralization of services, the emergency team was unable to arrive in the ten minutes they gave us”.

Half an hour later, when Johandri felt that he could no longer bear the pain, the train stopped.

Cortés obtained authorization from Ferromex for a Civil Protection team and firefighters to lower Johandri from the roof of the train. “The carriages are very tall, so getting her out required more careful coordination to avoid putting her at risk.”

Lifeguards, firefighters and a doctor from the railway company showed up. They climbed to the roof of the train, placed Johandri on a stretcher and tied her down. The Venezuelan paramedic released her hand shortly before several migrants helped her down the side of the car, next to the stairs where she boarded El Bolichero.

Cortés explains that the stretch from Irapuato to Torreón, known as the central route, is the busiest at the moment for migrants crossing Mexico to reach the United States.

“The increase was recorded this year because The Gulf route, which is the shortest by train and the one used by the most impoverished migrants, is highly criminalized”.

Given the increase in the flow of migrants boarding trains, Ferromex suspended the operations of 60 trains on September 19, to avoid the risk of injuries or death in transit.

Johandri was taken by ambulance to the Pabellón de Arteaga General Hospital, in Aguascalientes. Doctors said her cervix was five centimeters dilated and she was in an advanced stage of labor.

Mia was born without setbacksaround noon on Friday, August 25, 2023.

Through the lawyer, officials from Mexico’s National Immigration Institute visited Joahndri and confirmed that her daughter would obtain Mexican nationality and that the family could legally remain in the country.

“I’m very grateful because my daughter and my family are safe,” says Johandri, from the shelter in Aguascalientes.

“Although we can stay in Mexico, I haven’t lost the dream of reaching the United States”.

Source: Elcomercio

I am Jack Morton and I work in 24 News Recorder. I mostly cover world news and I have also authored 24 news recorder. I find this work highly interesting and it allows me to keep up with current events happening around the world.

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/WSGEFSUYYFB5RHRZ4PBIPUXISA.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/YKLAG5QWKZAQZJ6PUHGDNJ2IEE.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/3A7Q7GEUQFECXMF7KS4PNOQOY4.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/SLSM2XB4FZGS5AH7Y6M2GZ7YTA.jpg)