You’re about to read one of those articles that should carry the warning that it may offend your sensibilities, because it probably will..

It’s about the children’s fireplacewho lived in brutal conditions working as a chimney sweepsa practice that has been remarkably widespread and socially accepted for a long time in different parts of the world.

LOOK: The fascinating (and not so well-known) life of Josephine Bonaparte, Napoleon’s first wife

With no option of escape, the children endured long hours, horrific treatment and atrocious working conditions.

Some, as young as 3 years old, were often orphans or sold by poor parents, leaving them at the mercy of their masters or “masters”, who forced them to carry out work, no matter how dangerous it was.

And it was. Extremely.

In the late 18th and 19th centuries, the British press frequently contained reports of deaths of so-called “climbing boys”.

Some fell from roofs or chimney structures; others were trapped in them and suffocated; and there were even cases of children being roasted alive after being forced into still hot or lit fireplaces to put them out.

One such tragic incident occurred in Limerick, Ireland in 1846.

Michael O’Brien, 8 years oldhe died trapped in a chimney whose soot caught fire that day.

At the coroner’s inquest, Catherine Ryan, a domestic worker, testified under oath that she heard the boy’s master, Michael Sullivan, order her to clean herself and, about 15 minutes later, the boy. scream saying it was burning.

When he came out, “Sullivan grabbed him by the leg and hit him with a leather belt so hard that the boy knelt down and said, ‘I’m going to the top of the house and down the chimney.’ I saw Sullivan take him by the arm and lead him up the stairs; subsequently, the child was taken dead from the chimney”.

The Limerick and Clare Examiner reported that his body was found “in a terrible state, with the skin severely burnt and disfigured”, and that, following the inquest, a verdict of accidental death.

That was the usual verdict, and only in a few cases – like this one, because of public opinion – was anyone eventually guilty.

And it wasn’t just in Ireland.

Although in places such as Scotland and Russia alternative methods have been used for this task – such as lowering a brush with a weight tied to a rope down the chimney or flue – in England, France, Belgium, Switzerland, the Netherlands and probably also In other places there were chimney sweep children.

In Italy they were known as sPazzacaminiand in the north of that country They trained orphans and beggars to work abroad.

In turn, in the winters of the 19th and 20th centuries, impoverished families in Swiss regions, such as the canton of Ticino, in the Alps, handed over boys between the ages of 8 and 15 to Italian masters to work as chimney sweeps in Milan or elsewhere. Lombard cities, in conditions of semi-slavery.

In the United States, both before and after the abolition of slavery, young men who swept chimneys were generally African-American.

Why?

Although fireplaces existed since the time of the Roman Empire and were adopted especially in castles in the Middle Ages, it was only around the 16th century that they became more popular.

The aristocracy and bourgeoisie began to replace the traditional method of heating their homes by maintaining a central wood fire.

Soon, the working class also adopted them.

For those dedicated to cleaning, demand only increased and, in the 17th and 18th centuries, this was already a fully consolidated line of work, essential for preventing fires.

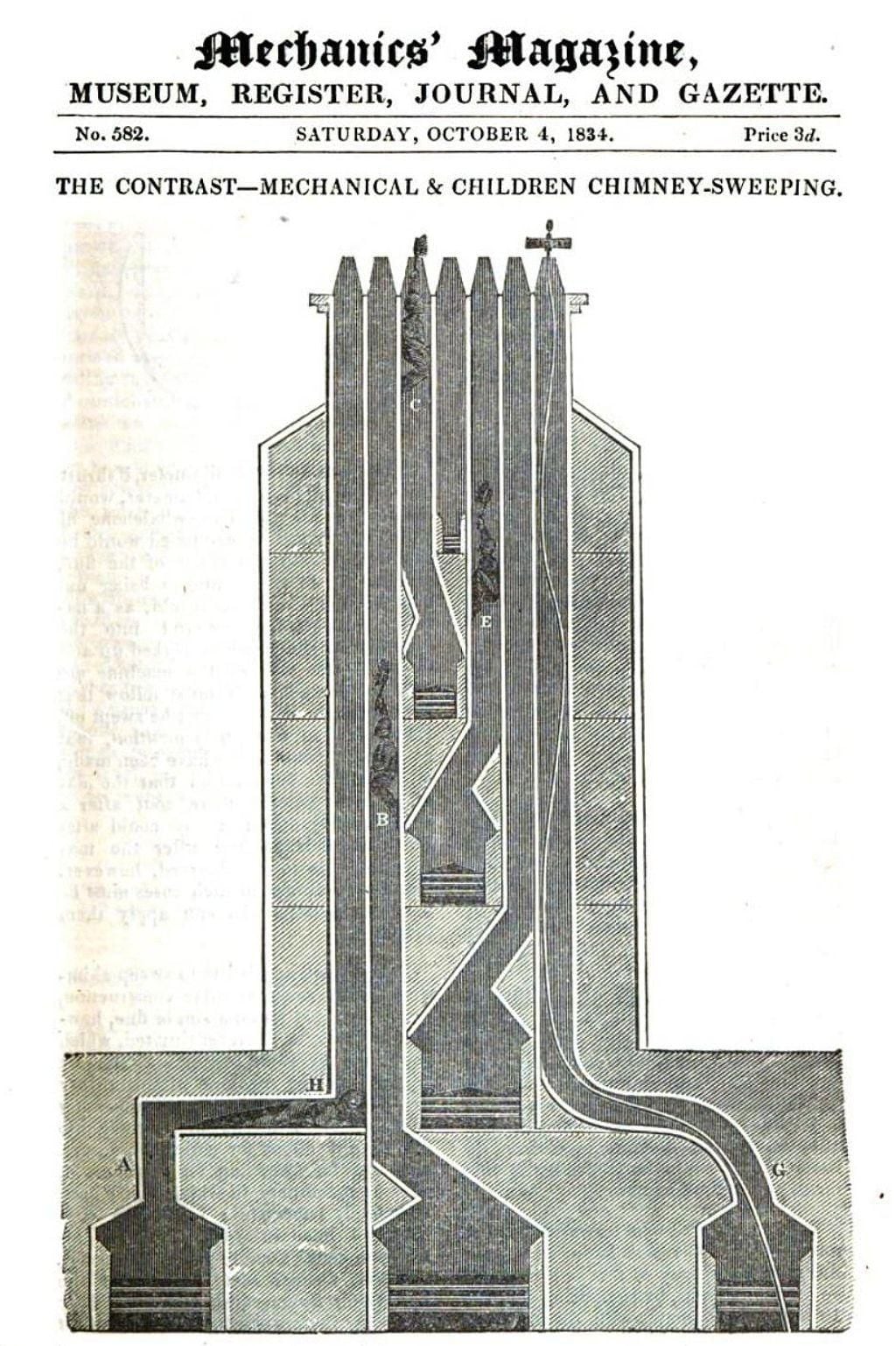

Only, When most people switched from firewood to coal, the design of chimneys changed: chimneys became narrower to create a better photo.

The standard duct was reduced to 36×23 cm, but there were narrower ones, up to 23×23 cm.

Furthermore, with higher-story buildings spreading to accommodate more and more people in cities, especially when the industrial revolution arrived, these ducts multiplied and were connected to heat more rooms in buildings.

Your runs may include two or more right angles and angled horizontal and vertical sections.

As a result, the chimneys became complex, angular, narrow and black labyrinths that made the task of cleaning them even more difficult.

If this were not done periodically, sticky, highly flammable soot deposits would block the chimney and homes would fill with toxic gases.

But who would fit – and be able to move – in those narrow, tortuous vertical tunnels?

With difficulty, the children

The small chimney sweeps then took care of the lives and health of their employers, but at a high cost to their own..

With ages ranging from four years to puberty, their still underdeveloped bodies suffered consequences such as bone deformity.

The intense and constant exposure to soot and its toxins caused since lung problemsby inhalation, painful inflammation of the eyes and, in some cases, blindness.

Often the chimneys through which they had to enter were still very hot due to the fire, some of which were still lit, which burned the skin or something worse.

A skin that, although it did not suffer from the heat, was left raw after incursions into the narrow ducts due to friction.

To the injuriesfull of soot, they became infected because they could not clean them, as, at best, they could bathe three times a year.

If they were not qualified enough, they could get stuck: His knees locked under his chin, with no room to free himself from this twisted position.

The luckiest were helped by pulling them with a rope, but if too much time passed before they were helped or the efforts were in vain, they were suffocating.

In cases of “accidental deaths” the only way to dislodge the bodies was to remove bricks.

With such dire consequences, the children had to be as strong and agile as possible to survive.

Those who were successful ran the risk of later suffering from a disease common in 18th century Europe, predominantly in England.

He was known as “chimney sweep cancer“, commonly known as sooty wart, which attacked the scrotum and affected boys when they reached adolescence.

Many doctors thought the cause was the venereal diseases that were prevalent at the time, but British surgeon Percivall Pott insisted the reason was different.

In 1775, he published a treatise showing a statistically significant association between soot exposure and a high incidence of scrotal cancer in hearth children.

Therefore demonstrated, for the first time in history, that cancer could be caused by environmental agents that act in humans as carcinogens.

And he identified the first industrial cancer.

All of this meant that the future of chimney sweep children was limited: It was unlikely that he would reach adulthood, much less old age..

The end, finally

The nightmare didn’t end when their work was done..

Without parents to guarantee their well-being or laws to protect them, children were at the mercy of strangers who considered them work tools.

Physical abuse was frequent and, generally, they were only given enough clothing to avoid being naked, but not to protect themselves from the cold, nor to change their clothes and avoid constant contact with soot.

They ate little and slept on the street or in the basement, wrapped in the same blanket they used to collect what they took from the chimneys they cleaned.

But their situation was not invisible to everyone..

Their lives have been explored in literature and popular culture, with authors such as British poet William Blake and French writer Victor Hugo capturing public attention.

Despite the efforts of influential people in all countries where this form of child exploitation was accepted, it took some time before it was banned.

In the United Kingdom, for example, following a campaign in the 1760s by philanthropist Jonas Hanway, a law was passed in 1788 specifying a minimum age of 8 for chimney sweeps.

But neither this nor other regulations were applied, until the death of yet another child gave the impetus for the necessary measures to finally be taken.

George Brewster was 11 when he became trapped in the narrow chimney of a Victorian hospital in Cambridgeshire.

Although they tore down a wall to reach him, he died shortly afterwards.

The 7th Earl of Shaftesbury read of her death and passed a bill in Parliament to end the use of children as chimney sweeps.

The 1875 law required chimney sweeps to be licensed and registered with the police, which required supervision of practices.

Thus, finally, the barbarity of the children of the chimney came to an end.

Source: Elcomercio

I am Jack Morton and I work in 24 News Recorder. I mostly cover world news and I have also authored 24 news recorder. I find this work highly interesting and it allows me to keep up with current events happening around the world.

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/ZXSE6NKPPJFPVBXSXELXRJHCZQ.jpg)