It was, at the time, the largest military operation on European soil after the Second World War.

It was also the first international intervention without prior approval from the UN Security Council, setting a precedent for the US invasion of Iraq four years later and a decision frequently used by the Russian president. Vladimir Putin to justify its invasions of Ukraine and Georgia.

LOOK: The origin of the mysterious “Ghost Army” that helped defeat the Nazis in World War II

On March 24, 1999, now 25 years ago, NATO launched a 78-day air campaign against the then Yugoslavia, after numerous political attempts to end the violent repression and murders of ethnic Albanians in Kosovo had failed.

NATO operations had predominantly military objectives in Serbia, Kosovo and Montenegro, while affecting crucial civilian infrastructure.

Belgrade authorities said that At least 2,500 people died and 12,500 were injured, but the exact death toll remains unclear..

Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International say around 500 civilians were killed in the airstrikes.

More than 300,000 Albanians fled Kosovo during the bombings and found refuge in neighboring North Macedonia and Albania.

The bombings ended in June 1999, when the Serbian leader Slobodan Milosevic accepted a peace agreement that called for the withdrawal of its forces from Kosovo and their replacement by NATO peacekeeping forces.

Twenty-five years later, NATO is still present in Kosovowith almost 5,000 soldiers on the ground, often caught in sporadic clashes between Kosovo security forces and the Serb minority.

Lack of UN approval

Years of diplomatic failures to reach a political solution to the Kosovo crisis culminated in another failed result in 1999.

Attempts by Western allies to negotiate a majority supporting military action in the UN General Assembly and to avoid a Russian or Chinese veto in the UN Security Council were unsuccessful.

Jamie Shea, NATO spokesperson at the time, stated that the vast majority of members of the UN General Assembly and the Security Council effectively supported NATO’s intervention.

“It’s not that there was no UN approval, there was no Russian approval”Shea told BBC Serbia.

“The campaign was a humanitarian intervention,” he said.

“It was designed to prevent human rights violations and violence against civilians, to allow the Kosovo Albanian population to remain in Kosovo.”

Although it blocked all UN efforts to adopt a joint position, Russia quickly adopted the so-called “Kosovo precedent” as justification for its own military interventions.

“In February 2008, Russia invaded Georgia under the pretext of protecting Russian speakers in the breakaway province of South Ossetia from the Georgian army,” said Kenneth Morrison, professor of history at De Montfort University in Leicester.

Morrison added that the same pretext was used when Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, although some developments immediately after the dissolution of the USSR pointed in a similar direction.

“Russia’s justification for military actions in 1992 and 1993 in Moldova and Georgia was also the protection of civilians from war crimes,” said political analyst Aleksandar Djokic.

“We could say that NATO also learned some lessons from Russia, and not the other way around.although Putin constantly reminds everyone of the ‘Kosovo precedent'”, he argued.

On the world map, NATO’s bombing of Yugoslavia had far-reaching consequences, far beyond the continent.

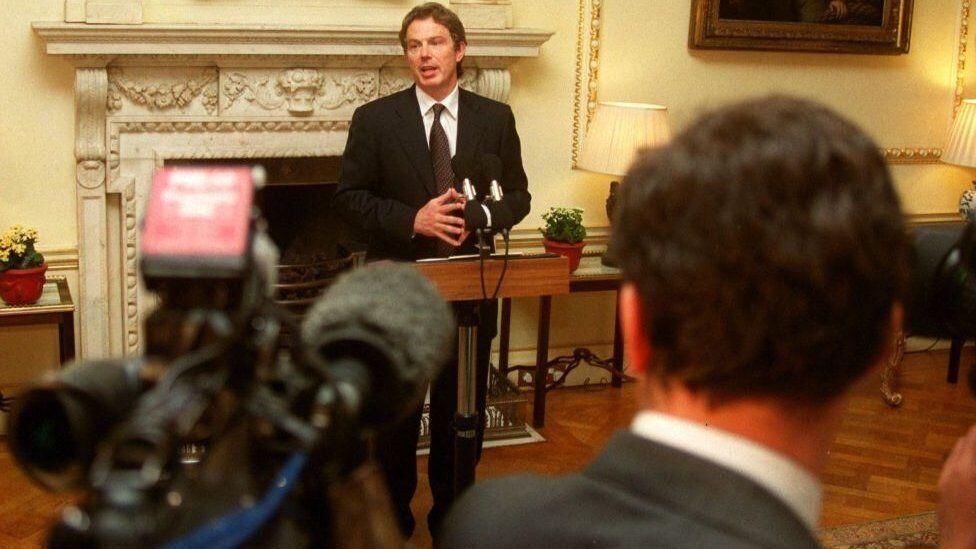

“Its architects, including British Prime Minister Tony Blair, considered the Kosovo campaign an unqualified success and proof that military force could be used to ‘free’ people authoritarian regimes or state violence,” said Kenneth Morrison.

“His belief that force could be used to achieve humanitarian objectives and confront authoritarian regimes, no matter how noble their principles, triggered a disaster in Iraq,” he argued.

A significant legacy

It is estimated that around 100,000 Serbs remain in Kosovo, supported by Belgrade. They predominantly reject the country’s independence.

“The NATO bombing left an important legacy, not least because it was an important factor in the subsequent fall of Slobodan Milosevic in October 2000,” said Kenneth Morrison.

“Also paved the way for Kosovo’s independence in 2008 and divisions within the international community regarding recognition,” he said.

“Subsequent tensions between Kosovo and Serbia, despite EU and US efforts to negotiate a normalization of relations, remained acute.”

Serbia says it will not recognize Kosovo’s independence and will never allow it to become a member of the United Nations. His position has strong support from Russia and China, among others.

Although two of the former Yugoslav republics, Slovenia and Croatia, have already joined the EU, Serbia and Kosovo are in a long accession process that largely depends on their success in normalizing mutual relations.

Mutual recognition is now a condition for EU membership for both Belgrade and Pristina.

Serbia also maintained a neutral military policy, although it cooperated closely with NATO through the Partnership for Peace project.

What led to the NATO bombings?

The former socialist Yugoslavia, which was once a proud example of the coexistence of numerous national and ethnic communitiescollapsed into a series of bloody wars in the 1990s.

Its six former republics became separate states, but then the Serbian province of Kosovo began to simmer with tensions under the government of Milosevic, who forcibly controlled ethnic Albanians pushing for independence.

Many Serbs consider Kosovo the birthplace of their nation, but of the 1.8 million people who live there today, 92% are Albanian.

In 1998, skirmishes between ethnic Albanian guerrillas from the Kosovo Liberation Army and Serbian security forces took a bloody turn and the conflict reached unprecedented levels of almost daily attacks and direct combat.

The international community sponsored a series of negotiations between Belgrade and Pristina in an attempt to avoid another serious war in the Balkans.

The latest, carried out for weeks in France, was triggered by the murders of 44 ethnic Albanians in January 1999.

Despite strong international pressure, the talks failed and Belgrade rejected the peace agreement that suggested the withdrawal of its forces and the introduction of a military presence led by the NATO in Kosovo.

Controversial goals

On April 24, 1999, missiles from NATO They struck the building housing the state television station RTS, killing 16 people and injuring 18 of its employees in the attack.

The alliance then claimed that the attack was justified because RTS was part of a “propaganda machine” by the Milosevic government, while Belgrade described it as a “criminal act”.

On May 7, when the Ministry of the Interior and the Serbian army headquarters were bombed, several missiles hit the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, killing three Chinese journalists and injuring more than a dozen of its staff.

The attacks ended on June 10, 1999.after an agreement was reached to withdraw all security forces under Belgrade from Kosovo and allow the arrival of 36,000 NATO-led peacekeepers.

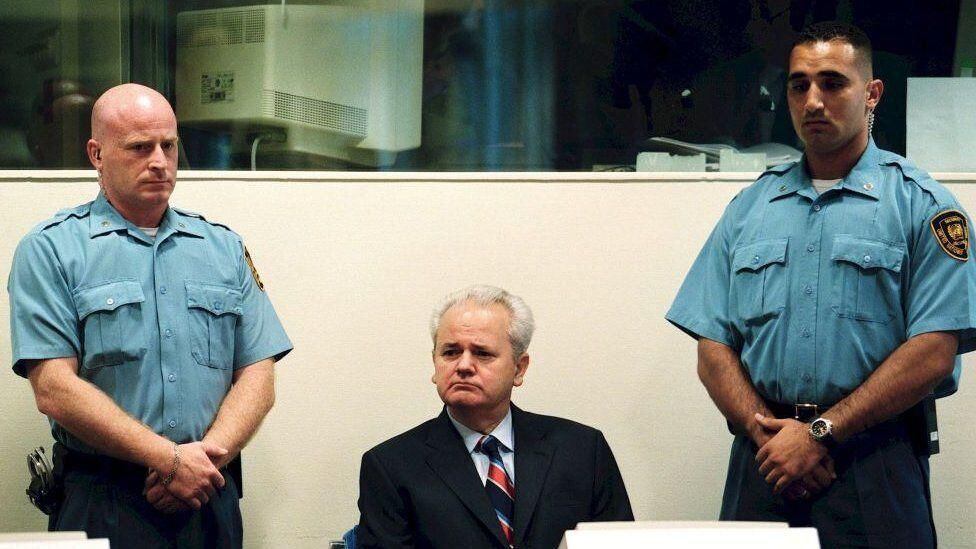

Slobodan Milosevic was deposed in a popular uprising in 2000.

Two years later, his trial began at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, where He faced 66 charges of crimes against humanity, genocide and war crimes..

He died in custody in 2006, before the sentence was handed down.

Source: Elcomercio

I am Jack Morton and I work in 24 News Recorder. I mostly cover world news and I have also authored 24 news recorder. I find this work highly interesting and it allows me to keep up with current events happening around the world.

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/IQL5A5234RBJDCCNGPB6AE4N7A.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/JM25IBFQDFHFFK4YZMOODBT4WU.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/JGMWAQN3YVBCFOLPBHZ7HFVKXI.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/PYBBKOVGC5HH3BFSADLGZPRBCA.jpg)