:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/3FI36ZCAVRB57OA5FMILCSDYCI.jpg)

If anyone has any doubts, let’s start by answering the question that plagues some foreigners who visit the city for the first time. Holy Week Spanish: No, it has nothing to do with the Ku Kluk Klan.

“It’s a continuous struggle”, explains Sevillian historian Manuel Jesús Roldán to BBC Mundo. “We have to do pedagogy every year to explain to those who come that this is an enormous wealth of centuries”.

LOOK: How Madrid became the “Miami of Europe” and how this affects those who live there

Roldán refers to the capirote, that cone that Nazarenes or penitents wear on their heads in Holy Week processions in Spain – and in some Latin American countries, such as Colombia -, and which is possibly one of their more recognizable icons.

But also to the celebration of Easter itself, a “living festival” that has evolved over the centuries, “and which, especially in southern Spain, has a festive meaning, is a curious combination of living passion and mixing it with the resurrection” .

From Palm Sunday to Easter Sunday, the streets of Spain are filled with faithful and curious people who come to watch the Holy Week processions, in which the different penitential brotherhoods or brotherhoods take place. steps with images of Jesus’ passion.

These enormous sculptures, which the costaleros carry on their shoulders, are accompanied by religious people, musicians and dozens of penitents, men and women who wear long tunics and, in most cases, carry a hood that ends in a peak.

This type of cone, made of cardboard and, more recently, also of plastic, originates from one of the most sinister institutions in the country’s history: the Spanish Inquisition.

The Holy Office

Those condemned by this institution, founded by the Catholic Monarchs in the 15th century to maintain Catholic orthodoxy in their territories, were forced to wear a hood or crown and a small tunic of thick fabric called “sanbenito” to identify and embarrass them during the acts of fe.

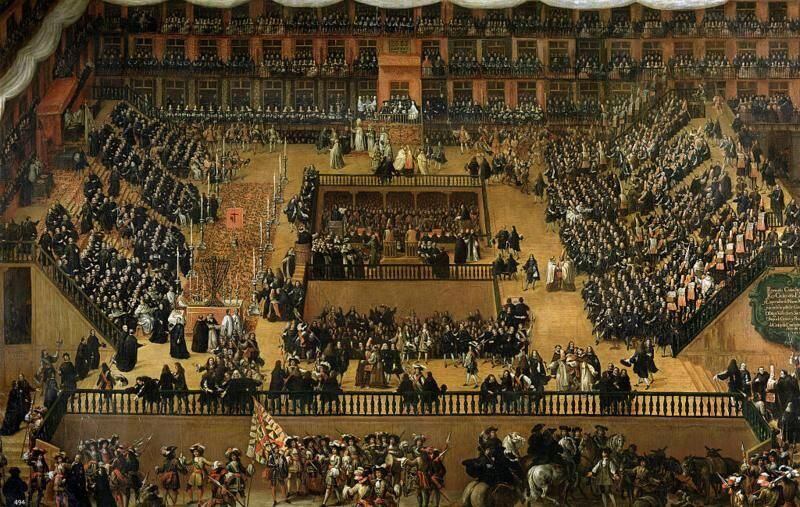

“The auto de fe was the great theater carried out by the courts of the Inquisition which had the objective, in theory, of reincorporating heretics into the Church, but which, in essence, what it did was bring people to public shame. This tainted them socially and excluded them from society.both the condemned man and all his descendants”, explains historian José Martínez Millán, author of “The Spanish Inquisition”, to BBC Mundo.

For three centuries, thousands of people were condemned in Spain by the religious courts of the Inquisition, accused of various crimes, which could range from blasphemy to heresy. Many of these convicts, especially in the early years, they ended up at the stake.

But first, the Inquisition gave them the opportunity to renounce their sins and proclaim their adherence to the Catholic faith. Those who did so, the “penitents”, obtained the grace of being strangled before being burned. Those sentenced to death who did not repent of their sins were cremated alive.

The autos-da-fé were celebrated in Public square, usually in the spring or autumn when a sufficient number of prisoners had gathered. A kind of stage was set up, where ecclesiastical and secular authorities and prisoners would sit, and it was even rehearsed the day before.

Weeks before, painters and tailors were hired to make the sambenitos and hoods that the condemned would wear. The designs and colors painted on them varied depending on the heresy.

“Some were simply carrying their jackets, others were much more painted, even simulating flames. These, obviously, went into the fire”, says Martínez Millán, professor of Modern History at the Autonomous University of Madrid (AUM).

Thus dressed, the prisoners were led in public humiliation to the place where the auto-da-fé was celebrated.

After the sentence was read, those sentenced to death were taken to the burner, which was on the outskirts of the city so that the “temporary arm”, as the civil authorities were called, could execute the sentence. The rest were forced to use the sanbenito throughout their sentence.

No forget

But the sentence didn’t end there.

The sambenitos and capirotes were then taken to the parish church to be hung in the aisles with the names of the condemned.

“From then on, at Mass they always had to sit under the sambenito, just like their children or grandchildren, the stain lasted for generations, which is one of the great cruelties of the Inquisition“, says Martínez Millán.

The expression “hanging the sambenito on someone” or “carrying a sambenito” comes from precisely this.

When a person wanted, for example, to enter university or apply for a military order title, they had to ask for a blood cleaning file in which it was demonstrated that, over three generations, no one was condemned by the Inquisition.

The sambenitos hanging in the churches served as testimony, and the only way to clear the name was to forget, but, as the AUM professor explains, “forgetting did not exist”.

The great autos de fé ceased to be celebrated in the second half of the 18th century, when they began to be organized within the institutions of the Inquisition, in what came to be called “autillos”.

One of them inspired what is possibly the most famous existing painting about the Inquisition, the painting Auto de fe de la Inquisición, by Francisco de Goya.

In its center, dressed in a hood and sambenito decorated with flames, a condemned man listens to his sentence with his eyes downcast and a resigned attitude, while a crowd of clerics, authorities and unidentified figures generates a suffocating atmosphere. Next to the stage, three other convicts, who also wear crowns, wait their turn.

It’s unclear how this cardboard cone made the jump from the Inquisition to Easter celebrations.

penitential brotherhoods

However, historians believe that the penitential brotherhoods adopted this hood, which due to its shape also symbolized the attempt to get closer to God, having seen it in those condemned penitents.

The first brotherhoods that were formed in the 15th century, after Saint Vincent Ferrer preached penance, and which went out in procession, were very different from those known today.

Penance involved flagellation, so these men stripped their backs and whipped themselves with ropes and chains in a bloody spectacle.

At this point “they begin to demand the cult of the True Cross and the blood of Christ, then a series of images begin to appear on the street, which is usually a crucified person”, explains Manuel Jesús Roldán.

This crucifixion of the True Cross extends throughout Spain and Latin America.

The penitents were anonymous, They covered their face with a mask and they wore a tunic of coarse, cheap material, generally white.

Historians agree that the first of these brotherhoods to adopt the hood at the end of the 16th century is the Seville Brotherhood of Hiniesta, which has medieval origins and continues to exist today.

“O Hiniesta Brotherhood He adapts that cardboard cone to the mask that his penitents wore and begins to differentiate two types of brothers: the ‘brother of blood’, who flagellated himself and had his mask fall back, and the ‘brother of light’, who was in charge of carrying a candle and wearing a hood”, says Roldán, author of “Holy Week Stories They Never Told You”.

In the 17th century, most brotherhoods in Spain already used this cone, giving another presence to the penitents, who at that time came to be called Nazarenes.

Each brotherhood adopted a color. Many chose purple, which was penitential; but a little red, for its sacramental symbolism; others green, for the cult of the True Cross; and others kept white or adopted black, which became fashionable at the end of the 18th century.

Since then, the brotherhoods and processions were on the verge of disappearing with the arrival of Charles III to the throne. “Penance was something that conflicted with the ideas of the Enlightenment, which is why it was forbidden to publicly whip oneself in the street, cover one’s face with a mask and go out at night”, explains the Sevillian historian.

After the War of Independence and the return to absolutism, the brotherhoods returned to their activity. But penance, which was already considered a thing of centuries past, was never recovered.

Today the Holy Week processions in Spain They go far beyond the religious and are part of a popular culture “that has a sense, festive, identity, which is linked to the return each year to a date, to a known people, to a feeling of a city and to a way of living “. understand the life that keeps this party alive”, says Roldán.

The historian recalls that some interpretations link them to the important substratum of classical Roman culture that exists in Spain, where the spring festivals were celebrated at the end of March.

“Although the processions are very serious and rigorous, they also have that traditional festive meaning,” argues Roldán, “so it is difficult to make outsiders understand that those who dress up as Nazarenes are not only gentlemen anchored in the past, but can also be young, old, women, men, people on the left, on the right… There are even atheists!“.

Source: Elcomercio

I am Jack Morton and I work in 24 News Recorder. I mostly cover world news and I have also authored 24 news recorder. I find this work highly interesting and it allows me to keep up with current events happening around the world.