Wanted: multilingual ex-soldiers willing to go undercover into Ukraine for the attractive sum of up to $2,000 a day, plus a bonus, to help rescue families from an increasingly grim conflict.

The text above sounds like something out of an action movie script, but it is an actual job ad, taken from the employment website Silent Professionalsdedicated to people who work in the military and private security industry.

SIGHT: The “children” of the USSR who are now escaping Russian attacks in Ukraine

And, experts say, demand is growing. Amid a wrenching war in Ukraine, US and European private contractors say more and more opportunities are emerging ranging from people “extraction” missions to help with logistics.

Robert Young Pelton, a Canadian American author and expert on private military companies (PMCs), states that there is currently “a frenzy in the market” of private contractors in Ukraine.

- “Putin’s action is so irrational that it goes beyond what happened during the Cold War”

- What is a war crime and what are the accusations of the Ukrainian government against Russia

- What impact are the weapons sent by the West to Ukraine to combat the Russian invasion having?

But the demand for paid security workers, many of them ex-soldiers trained to fight and kill, in the midst of war leaves plenty of room for error and has the potential to spiral into chaos.

Complex and well-paid operations

Even as Western volunteers join the fight in Ukraine, for which they can expect to be paid the same as their Ukrainian counterparts, private actors are offering money for security services like the one advertised on Silent Professionals.

The platform did not say who was behind that job offer, but according to Pelton, these companies are being contracted for between US$30,000 and US$6 million to help get people out of Ukraine. He explained that the higher figure is for entire groups of families who want to leave with their assets.

Tony Schiena, CEO of Mosaic, a US-based intelligence and security advisory firm that already operates in Ukraine, noted that the price of evacuations depends on the complexity of the work.

“When there are more people, the risk goes up. Children and families are more difficult. It all depends on the methods we use to get them out,” he said.

Mosaic’s missions are largely intelligence-driven, rather than weapons-driven, said Schiena, a former South African intelligence officer whose firm includes several former high-ranking U.S. intelligence officials on its board.

They are working with private clients, corporations and PEPs (politically exposed persons) to help them get out of UkraineSchiena told the BBC.

He claimed that among his clients is an “intelligence agency of a fairly large country” that wants to get its citizens out.

“Depending on how the conflict develops, I think there will be a constant demand for [CMP]. There is a constant need, and as [la guerra] escalate or de-escalate, there will always be something that they propose to do for us,” Schiena said.

The rise of a controversial industry

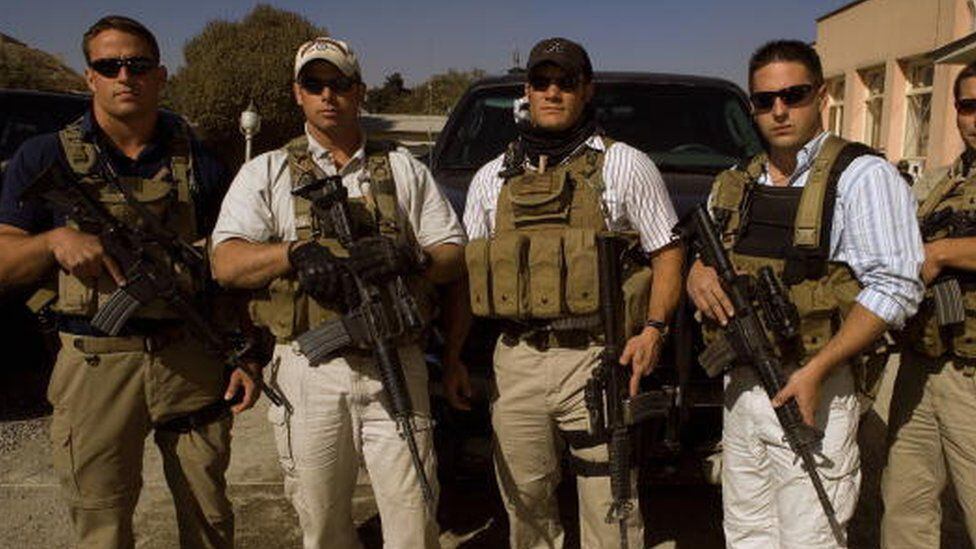

Private military and security companies have been around for decades, but recently gained notoriety during the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan after 9/11, 2001, working on behalf of Western governments and business interests.

At the height of the Iraq war, tens of thousands of private contractors – like Blackwater’s – were operating there. Their tasks ranged from armed missions such as convoy protection to feeding and housing troops on military bases.

The Blackwater company made headlines after a series of high-profile incidents, including the deaths of 14 Iraqi civilians shot dead by its contractors in Baghdad in 2007.

In Eastern Europe, private companies have long been used to protect wealthy individuals and corporations.

During the breakup of the former Yugoslavia, several companies were also contracted to help equip, train, and organize Bosnian and Croat forces, all with the blessing of the US government.

The nature of this industry means that it is difficult to track the money it moves and the number of contractors, but overall it is a growing sector.

A report of Aerospace & Defense News found that the global private security and military industry will be worth more than $457 billion in 2030, up from $224 billion in 2020.

Contractors or mercenaries?

Foreign military contractors say they are not fighting in Ukraine.

Some say they are being approached to help NGOs and humanitarian organizations in Ukraine or neighboring countries that need people with specialized skills and experience to work in difficult conditions in conflict zones.

“Most of the guys I know personally who are going are doctors, physician assistants, paramedics, nurses and former special operations officers, who are combat veterans,” said Mykel Hawke, a former US special forces officer. who has worked as a contractor in war zones.

Western contractors abide by the laws and regulations of their own countries, said Christopher Mayer, a former US Army colonel who worked with CMP in Iraq.

They are supposed to protect people, places, or property, rather than engage in direct combat.

Many in the industry bristle at the suggestion that they are ‘mercenaries’ or fortune hunters.

“It’s the same type of work that you see in the United States and elsewhere. The difference is that in conflict areas, the likelihood of having to use deadly force is much, much higher,” Mayer said.

In practice, however, the border is blurred.

“If you have the skill set to be a private contractor, you have the skill set to be a mercenary. There is no clear line between the two,” said Sean McFate, a former U.S. paratrooper who later served as a contractor in Africa and in other places.

“It all comes down to market circumstances and the decision of the individual person. People talk about legitimacy and who the customer is. None of that matters. If you can do one thing, you can do the other,” he added.

big risks

The proliferation of CMPs can lead to both “chaos” and good, he warned.

“Mercenaries historically prolong the conflict for profit. There could be a point by mid-century where super-rich people have private armies.and I don’t know what that’s going to look like,” he added.

Examples of such companies taking an offensive approach to conflict include South Africa-based Executive Outcomes, which fought on behalf of the government of Angola and Sierra Leone in the 1990s.

London-based Sandline International has been involved in conflicts in Papua New Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone.

And members of Russian mercenary groups are said to be on the ground in Ukraine.

But Simon Mann, the former British special forces officer who founded Executive Outcomes and Sandline, told the BBC that the possibility of using Western contractors for offensive missions in Ukraine is “highly unlikely” and would raise complicated legal and organizational issues.

“How [serían] funded? How [serían] commanded? Where would they fit into Ukraine’s order of battle?” he wondered. “Would they be properly enrolled in the national armed forces before any operations? If not, what would be your legal position? Low? Medical coverage? Death and disability insurance?

Mann, who spent several years in prison after being accused of leading a failed coup in Equatorial Guinea in 2004, said he is nonetheless aware of evacuation missions charging about $13,000 per person, “mostly organized by by people linked to CMP who happen to have contacts on the ground”.

Some have warned that even paid rescue missions in Ukraine could be fraught with danger for both contractors and clientsand that the industry is inundated with people who misrepresent their ability or experience.

Orlando Wilson, a former British soldier and longtime security contractor, said he believes most talk of private contractors in Ukraine is “garbage”.

“I don’t see how people can operate in Ukraine right now, at least not privately,” he said.

“If you get caught by either side or one of the militias, they’ll just take you as a spy and that’s it. It wouldn’t be safe for the people who do it and it wouldn’t be safe for the customers,” Wilson warned.

___________________________________

- Change of command 2022: what time is it, where to watch it, traffic closures and more

- Putin says Western sanctions are like a ‘declaration of war’

- Ukraine shows on social networks the missile attack on a helicopter: “This is how the Russian occupiers die!” | VIDEO

- Visa and Mastercard suspend operations in Russia due to the invasion of Ukraine

- The strange act of Vladimir Putin between jokes, flowers and stewardesses in full offensive in Ukraine

- British journalists recorded the moment they were fired upon by Russian troops in Ukraine

- War correspondent in Ukraine: “No one imagined that this would happen with such brutality”

Source: Elcomercio

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/NTKDEXO5ZZBAXIKU5CNE43AQI4.webp)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/46T6IPFMYJE4FASQSIEJG4ENZI.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/3FPN7BXXWRHYFJVRDEXG77LLTI.jpg)