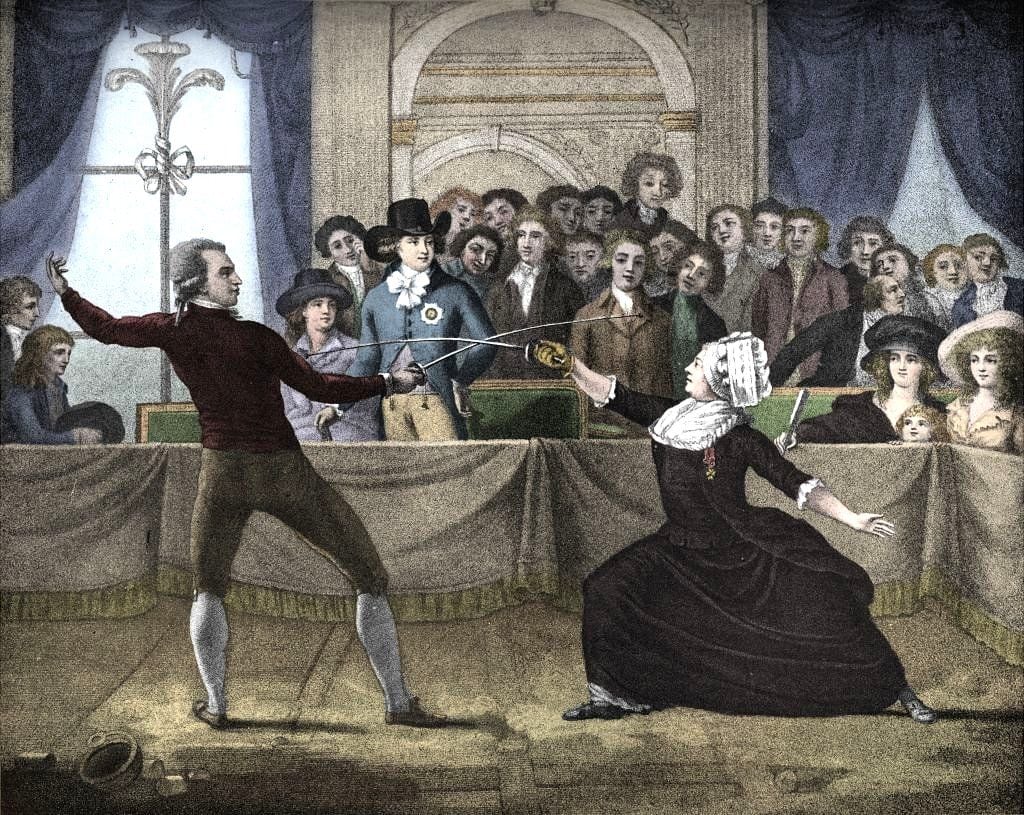

“It must certainly be admitted that she is the most extraordinary person of the age … we have not seen anyone who has united so many military, political and literary talents,” said the British “The Annual Register” of the year 1781, referring to the lady who appears pictured above with the Grand Cross of the Royal and Military Order of Saint Louis of France.

He is the Knight of Éon, a famous, charismatic, talented and intriguing soldier, diplomat and spy of the 18th century, who aroused the fascination of his contemporaries.

Look: How a priceless Roman bust ended up in an American thrift store

And if you’re already confused by the pronouns we’ve used, get used to it: D’Éon lived openly as a man and a woman in France and England at different stages of life, attracting public interest and the attention of the French Crown.

Although tracing her story is not easy, since it is full of contradictory stories, speculations and rumours, her biography “The military, political and private life of Mlle. d’Eon”, and the surviving personal correspondence, provides a great deal of information in his own words.

Gary Kuts drew on them for his book “Monsieur d’Éon is a Woman,” telling the BBC that D’Éon “had a complex range of ideas and philosophies about why crossing the gender line was so significant.” ”.

Charles

Charles-Geneviève-Louis-Auguste-André-Timothée d’Éon de Beaumont was born into a noble family in Tonnerre, France, on October 5, 1728, and it was clear, even at a young age, that he was a prodigious learner.

“My family has lived in Tonnerre for the last 12 centuries, and the Chevalier is the most prominent relative,” Philippe Luyt, a descendant of D’Éon, told BBC Reel.

“He had an extraordinary and very complete education. Voltaire said of him: ‘I discovered the most brilliant man of the century’”.

“Then Louis XV gave him a ministerial position. From that moment on, he had an extraordinary life.”

D’Éon was sent as a diplomat to secure relations with Empress Elizabeth I of Russia as a potential ally against a war with Britain and the Prussian Empire.

He returned to France with the news that Russia would join the Franco-Austrian alliance.

As an established officer, he served briefly in the latter half of the Seven Years’ War.

But with the Franco-Austrian alliance suffering catastrophic losses, the king ordered him to go to London to negotiate the terms of a peace treaty with the British.

“Since Louis XV never expected to obtain peace after such a defeat, he said: ‘Not only D’Éon is my best secret minister, but also my best officer in the Seven Years’ War,’ and gave him the Cross of Saint Louis”, says Luyt.

“At that time, and ever since, Charles D’Éon became Chevalier D’Éon.”

knight

D’Éon returned to London as temporary French ambassador to England.

and also as member of the Secret du roia network of spies that acted as an unofficial channel on behalf of the king.

“As strange as it seems today, King Louis XV, in addition to managing an official diplomatic core, also had an espionage organization that was unknown to that diplomatic core and sometimes went against the policies of the Foreign Minister,” Kuts explains. .

In London, D’Éon made a name for himself, charming and pleasing many in British high society with exuberant wine-soaked gatherings.

But, on October 4, 1763, he received an official request from the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs to resign his position and return to France.

and refused to do it.

“It is an extraordinary step that made him a a kind of outlaw”.

“He stayed in England and lost his diplomatic post, but he kept the role of spy and began to blackmail the French king with that role.”

Gentleman or lady?

In 1770, rumors began to circulate that the exiled Chevalier D’Éon was actually a woman.

For a long time, both in the United Kingdom and in France, it had been speculated that Chevalier was a woman.

“They say that even when he was dressed in full soldier’s uniform, people sometimes mistook him for a woman dressed as a man, and rumors spread that he really was a woman,” says Jane Hamlin, president of The Beaumont Society.

“Yes, others have said that he himself was spreading the rumors”.

Over the next few months, the voracious British press was plagued with stories about the Chevalier’s true biological sex, and having achieved near-celebrity status by 1771, London bookmakers even began to bet on his gender.

“D’Éon gave his own answers”, says Catherine Arnold, author of “City of Sin: London and its vices”.

“If they asked her: ‘Are you a man or a woman or what are you?’, she would say: ‘I was born a girl. But my father, a Burgundian nobleman, had fallen on hard times and so that I could inherit, he decided to raise me as a boy.’”

“In the very broad-minded social circles you lived in, that was very understandable.”

From late 1777 onwards, the Chevalier began to present himself permanently as a woman.

Prison for attire crime

In 1774, Louis XVI ascended the throne wishing to cease the Secret du roi and clean up his grandfather’s diplomatic history, so negotiations between D’Éon and the new French court finally began.

In exchange for handing over his secret diplomatic documents, D’Éon demanded that the French court provide him with a pension and officially recognize him as a woman.

“D’Éon wanted to be recognized as a woman, to live as a woman, but also to retain the right to wear the military uniform of a French officer, as she didn’t like women’s clothing,” says Kuts.

The king, convinced that d’Éon was biologically female, agreed to d’Éon’s terms, but on one condition.

“Louis XVI intervened and said: we will pay for a trousseau but you have to wear those feminine clothes”.

“He showed up at Versailles in a tribute to Louis XVI dressed in a Marie Antoinette suit, but he didn’t shave and he kept his boots on,” says his descendant Luyt.

“The people loved it and the king ordered him never to take off his women’s clothes.”

“But D’Éon refused, so they jailed him in Dijon until he changed his mind”.

“After a year, D’Éon gave in and was exiled to Tonnerre as a woman for 7 years.”

“D’Éon reluctantly agreed,” says Kuts.

“He wore women’s clothing, but also the Saint Louis medal, his highest military honor, which to an 18th-century viewer was absurd.”

gender issue

After years of exile, he was finally allowed to return to London, provided he continued to dress for women.

D’Éon was still entitled to an annual pension.

“You could cynically say that D’Éon wore women’s clothing to retain the income from that pension annually, except that when the French Revolution happened all the nobles lost their pensions,” Kuts stresses.

“Therefore, the only reason d’Éon continued to dress in women’s clothing is because he chose to.

“Now, the question is why D’Éon got involved in that gender transformation, and my point of view is based on his rich autobiographical manuscripts”.

“There’s no question that she was trans or transgender, but in the 18th century she was different in the sense that she wasn’t someone who ever said to herself, ‘I was always trans. I always felt like a woman.’”

“I saw femininity as something I had to achieve, as a moral purification. That was what femininity did for D’Éon: it allowed him to live a more moral life.”

Nonetheless, Kutz stresses, “trans people today would rightly identify D’Éon as a trailblazer, because he made that momentous journey across the gender line.”

The truth

When his annual French pension was discontinued and money was tight, D’Éon began fencing displays dressed as a woman, wowing the public and becoming a celebrity.

Finances, however, remained tight and, despite the fame and notoriety that had accompanied her singular life, D’Éon died in poverty in 1810, aged 81, after living for 15 years in London as a woman. , sharing accommodation with a widowed friend, Mrs. Cole.

It was she who found his lifeless body.

When he started to undress him, A gasp escaped her at the sight of D’Éon’s penis.

“Cole had never imagined that he was a person with normal male genitalia,” explains Kuts.

Since the matter had always been so controversial, the old woman decided that medical corroboration of her discovery was necessary.

He called in a committee of experts, including an anatomist, two surgeons, a lawyer, and a journalist, who examined the body and dissected it to determine if there could be any genuine doubt about the Chevalier’s biological masculinity.

Before the dissection, the artist Charles Turner was summoned to make the drawing on which the print below was based, in order to record the sex of d’Eon, explains the British Museum.

The inscription below the image reads: “Drawn from the body of the Chevalier D’Eon, May 24, 1810.”

“’I hereby certify that I have inspected and dissected the body of the Chevalier D’Eon, in the presence of Mr. Adair, Mr. Wilson and Le Pere Elizee, and have found the male organs to be in all respects perfectly formed. May 23, 1810. Golden Square”.

“As a consequence of a note from the undersigned Gentleman, I examined the body, which was a Male; – Original Drawing was made by Mr. C. Turner, in my presence. Dean Street, Soho. May 24, 1810″, and inscribed “London Published June 14, 1810 by C Turner.”

It is not clear how many impressions of this plate were printed, nor if it was intended for a specialized audience or for sale to the public, the British Museum clarifies.

In any case, “it was then that the European public first learned that the story they believed to be true was in fact the reverse than they thought,” says Kuts.

“That is, the Chavalier was born a man and lived the second half of his life as a woman.”

*Based on the video of BBC Reel “The Chevalier d’Éon: The 18th Century transgender spy

Source: Elcomercio

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/GE4DCNBNGA2S2MBYKQYDAORRHA.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/DS2NUGPF3REOFB7QUFCGKIH57U.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/GTLM4W3GQNDQ5PDQH4MTD5R3II.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/2GIWGRTUSBEKJNO3HLXMSFO3ZA.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/OUCK3CDJVBCFDGYF5OJMJXFZQI.jpeg)