:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/GE3TCMZNGEYC2MZRKQYDAORRG4.jpg)

“No Brazilian will go hungry” was one of the slogans that marked much of the two governments of Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva (2003-2010).

It was eight years in which not only nearly 30 million people came out of poverty, but the so-called “new middle class” also emerged in the arms of an economic boom that generated jobs and placed the country among the fastest growing emerging economies. .

LOOK: 3 reasons that explain Lula’s victory and his return to the presidency 12 years later

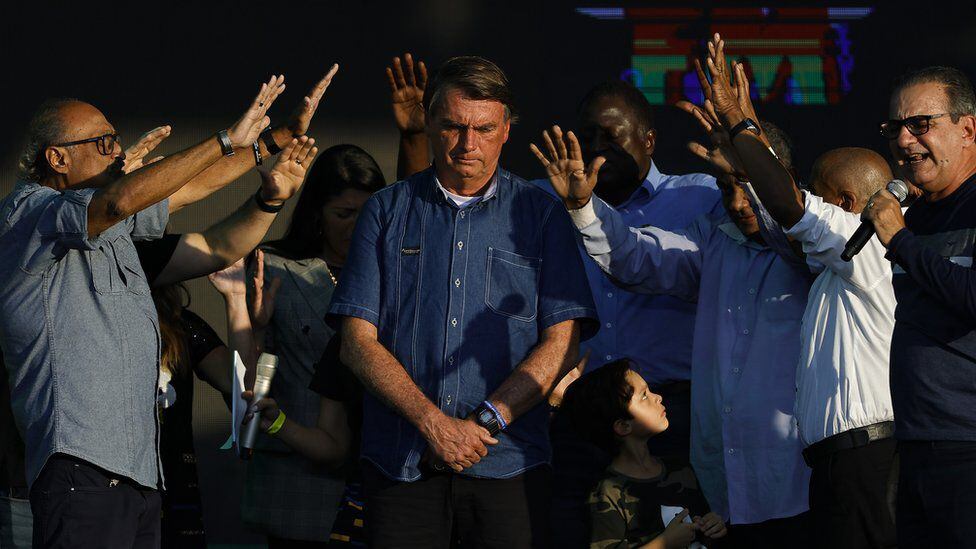

And this Sunday, by winning the elections by a narrow margin over Jair Bolsonaro, he repeated it again.

“The most urgent commitment is to end hunger,” he said 12 years after leaving office.

“Brazil experienced the greatest social transformation we have seen so far,” says Mónica de Bolle, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE), in Washington, DC, referring to the social mobility the country experienced at the time.

According to the World Bank, between 2001 and 2011, Brazil’s GDP per capita (the sum of all the wealth produced in the country, divided by the number of inhabitants) grew by 32%, while inequality decreased by 9.4%. and the percentage of people living in poverty and extreme poverty was cut in half.

Although some of these achievements are attributed by experts to the economic policies initiated by the government of Fernando Henrique Cardoso, Lula’s predecessor, the president-elect is recognized for his ability to carry out his social agenda with openness to markets and responsibility. fiscal, taking advantage of the benefits of the boom in commodities and allaying the fears of investors when they saw that a socialist came to power.

Criticized for the increase in violence and drug trafficking when he was in power, and fallen into disgrace after the Lava Jato corruption scandal was uncovered, which landed him in jail for 19 months and for which he still has pending cases, Lula finished his mandate with an approval percentage of 82%.

Outside its borders, analysts believe that the former president was skillful in managing relations with countries as antagonistic as Venezuela or the United States, and within the

G20 (the group that brings together the world’s largest economies), despite the harsh criticism it received for its links with Iran.

Twelve years after his departure, however, the world has changed vertiginously and the international context that he will have to navigate is very different from that of the early 2000s, as is the Brazil that he will govern when he arrives once again at the Planalto in January. of 2023.

The fight against poverty and economic growth

When the former union leader and one of the founders of the Workers’ Party (PT) came to power in 2003, the fiscal situation was complex.

With the push of the strong economic growth experienced by the country hand in hand with the boom in commoditiesthe Lula government had at its disposal the necessary resources to finance and expand social programs such as the emblematic Bolsa Familia or Hambre Cero.

“Bolsa Familia was almost a social revolution in Brazil”explains the associate researcher of the Public Policy Analysis Council of Fundação Getúlio Vargas (DAPP-FGV) and journalist, Thomas Traumann.

The families received financial aid, he says, which was delivered directly to the women, a formula that was also applied in other housing or land delivery programs, which were registered in the name of the women, something considered by the analyst as a key to the success of these initiatives.

A success of the social programs that other analysts such as Bruna Santos, senior adviser to the Brazil Institute of the Wilson Center for Studies, considers to be the continuity of the policies created by former president Fernando Henrique Cardoso.

A program like Bolsa Familia “does not happen overnight,” he argues, but is rather the result of “incremental innovations” that had been taking place before he came to power.

In previous years, he explains, a social welfare network had already been created with economic support programs for family farming, the retirement of rural populations, gas subsidies, food allocations and other initiatives that were the origin of the policies that later Lula would implement it.

What changed, says Santos, is that many of those programs were unified into one: Bolsa Familia. And this occurred at a time of great flow of capital into the country that helped him govern “in abundance of resources and popularity.”

Something that several experts point out is that the former metallurgical worker born into an illiterate family was skillful in choosing his collaborators.

“Lula managed to make a good mix,” says Traumann, with more orthodox economists on the one hand, and a team technically qualified to be in charge of social programs, who constantly clashed with their views on how to manage government policies.

Another important thing that happened in those years is that the government, in addition to controlling inflation and debt, increased the country’s international reserves, a measure that allowed it to better face the financial crisis of 2008, in addition to gaining the confidence of the business and financial sector by demonstrating that it was committed to economic macro stability.

What economists of different persuasions agree on is that Lula had a good moment to lead the country.

Robert Wood, chief economist for Latin America and the Caribbean at the British think tank Economist Intelligence Unit, rescues the idea that the former president “was partly lucky” because Brazil was navigating the super cycle of raw materials.

That created the conditions that allowed for above-inflation increases in the minimum wage and, along with reforms to boost access to credit, paved the way for job growth.

On the other hand, he adds, the expansion of social spending helped reduce poverty and income inequality.

However, “insufficient progress on growth-friendly reforms,” Wood argues, left Brazil exposed as the commodity boom came to an end. “Since then, growth has been disappointing.”

Will it repeat the success of social programs?

Many of Lula’s supporters, especially those with lower incomes, voted for Lula with the longing to return to that time of abundance and strong social spending that allowed them to improve their living conditions.

In that sense, nostalgia for those good timesis part of the reasons that gave him victory in a climate of high expectations around the presidential figure.

Will it be able to meet such high expectations? Will the economy grow at such a fast pace that it will allow it to finance social spending to repeat the success of its social programs?

The response of the experts consulted by BBC Mundo is that it is practically impossible for the same conditions that existed at the beginning of the 2000s to be generated.

“The country is in another position. It does not have the resources to finance this type of program or increase the minimum wage as it did before,” says Mónica de Bolle.

And no less important, Brazil is not the same country that Lula governed because after Jair Bolsonaro came to power, there is now a new phenomenon: Bolsonarism.

“The Bolsonarismo is not willing to negotiate or build coalitions”says the expert. Therefore, one of the biggest challenges that Lula will have will be to govern with a Congress where she can only form partial coalitions and in which there is strong sentiment against the Workers’ Party.

The opposition coming from the Bolsonarista base, from the agricultural businessmen, from the evangelical church, “will be very hard,” Traumann points out. “This time there will be no honeymoon and it will be a very tense situation from day one.”

On the international front, the world is going through a completely different moment than the scenario that existed when Lula was president.

China, the main engine of the commodity boom, is in a process of economic slowdown; relations between Washington and Beijing are in a confrontational phase; The world is emerging from a pandemic and the war in Ukraine has destabilized much of the balance that existed in the past, making global politics much more unpredictable.

“Everything that was beneficial in your previous governments is now upside down”says de Bolle.

The bet of many Brazilians who voted for Lula was along the lines of “I want my glory back,” says Santos. The problem is that “no one can turn back the clock on a commodity export boom.”

Therefore, he says, “we should not expect miracles in the next four years.”

With a high probability that some of the developed countries will enter a recession, Brazil’s economic growth expectations for 2023 are quite low, with some experts, such as Robert Wood, projecting a growth of just 0.5%, which would tend to recover in subsequent years, as high interest rates and inflation subside.

But fiscal spending will be limited, he adds, by the high public debt. In this context, “it will be a challenge to replicate the improvement in socioeconomic conditions of Lula’s first two terms and although there will still be some gradual improvements, it is likely that he will not reach the achievements of 20 years ago.”

This, added to the strong Bolsonarista opposition, says Wood, predicts the arrival of difficult times plagued by social and political tensions that can affect governance.

Source: Elcomercio

I, Ronald Payne, am a journalist and author who dedicated his life to telling the stories that need to be said. I have over 7 years of experience as a reporter and editor, covering everything from politics to business to crime.