There are names of the pharaohs of the Old Egypt that have reached our days thanks to the Pyramids -Cheops, for example-, or to all his statues -Ramesses- or to the lavishness of his tombs. In this last category is Tuntankhamun.

The discovery 100 years ago of the tomb of that Egyptian pharaoh in Luxor is one of the most famous discoveries in modern archaeology, as it is the first known intact royal burial of that Egypt of pyramids, statues and pharaohs.

British Egyptologist Howard Carter’s phrase “everywhere shines with gold”, when he first looked inside the burial chamber he had helped to find, is the best summary of the wonder of finds that today are exhibited in various museums around the world. world.

But Tuntankhamen, the boy king who ruled in the 14th century BC. C, was not born with that name, but with that of Tutankhaton.

And in the change of that suffix one of the most critical and counterrevolutionary moments in the history of Ancient Egypt is reflected.

His predecessor, Akhenaten, had challenged the entire 1,500-year-old Egyptian religious system and brought the nation to the brink of the abyss.

His crazy bet, and that of his wife, Nefertiti, was to be monotheists.

Heresy

Akhenaten’s idea was dramatic and revolutionary: for the first time in history, a pharaoh wanted to replace the pantheon of Egyptian gods with only one, the creator of everything, the sun disk that crosses the sky every day, Aten.

He was the tenth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt and his reign began around 1353 BC. C. his name had also changed. He had been crowned Amenothep IV (meaning, “Amun is pleased).

The reign of his father, Amenothep III, had culminated in a series of magnificent parades held in Thebes (present-day Luxor), the religious capital of Egypt at the time and home of state god Amun-Ra. But, very soon, Amon would stop being happy.

What the follower of the sun disk was proposing was pure heresy; however, he was a pharaoh, a living god and could change everything: religion, politics, art and even language. And he did so.

decreed that the 2,000 traditional gods who had protected Egypt for more than a thousand years were relegated to the shadows.

It is hard to imagine what ordinary Egyptians felt. The concept must have been inconceivable.

The gods in animal and human forms were replaced by the Sun that illuminated the king with its rays.

For the traditional priests, who had dedicated their entire lives to the old gods and had been extremely powerful until then, it was a catastrophe.

They had practically ruled the country and suddenly they were redundant. Akhenaten began to acquire dangerous enemies.

And the following announcement from the royal couple was just as surprising.

Pharaoh and his wife would leave the ancient and sacred city of Thebes, the heart of the entire nation, and head north up the Nile River in search of a new utopia.

other capital

It was the fifth year of his reign, and Akhenaten clearly wanted to break with the past.

He gave Nefertiti the title of Great Royal Wife and equal powers.

together they traveled about 320 kilometers until they reached what is now Amarna, where they built a city they called Ajetatón, which means Aten’s Horizon.

On a rock that is still on one of the hills there is a public proclamation composed by Akhenaten that explains the reason that led him to choose precisely that place.

It is said that the great sun god told them: “Build here.” How did he tell you? With a sign.

The place is surrounded by hills and at certain times of the year the Sun rises through a crack creating the hieroglyphic shape of the horizon.

Aton, the pharaoh interpreted, was indicating where he should build his sacred city.

And so he did, at breakneck speed.

Thousands of people from faraway Thebes were brought in to build, decorate, and manage the new capital in which they came to live. up to 50,000 people.

They dug wells, planted trees and gardens; the arid desert flourished. They built beautifully decorated houses and palaces, as well as temples to the one god.

Akhenaten’s vision of a religious utopia gradually became a reality.

revolutionized art

Amarna became the new political and religious heart of the nation, the center of a new cult.

Not only the capital and religion changed.

His revolution brought other innovations that we can see thousands of years later.

Detailed engravings found at Amarna reveal how the royal family lived.

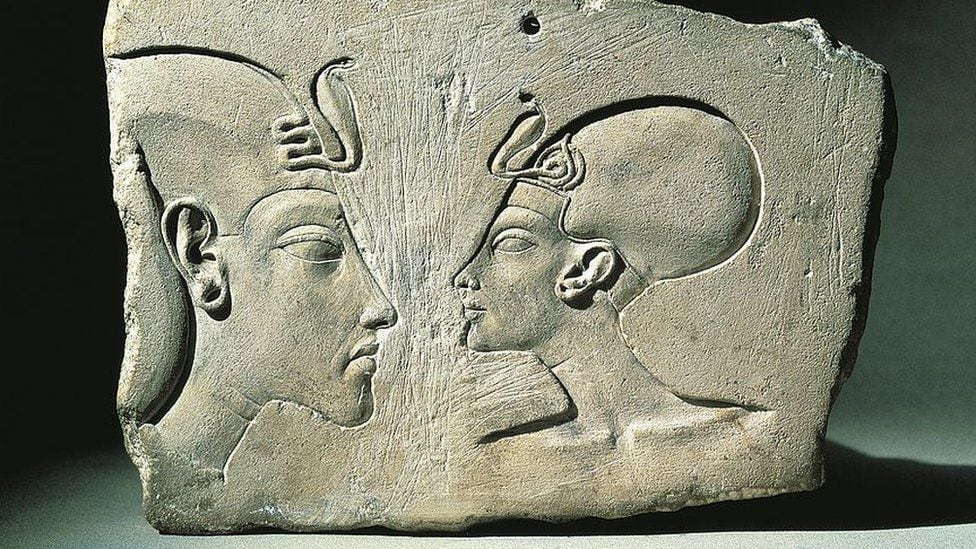

Images show Akhenaten and Nefertiti hugging his daughters. Until then, no Egyptian royal family had been portrayed showing affection.

Compared to earlier Egyptian art, which tends to have a static and monumental quality, as if designed to last forever, these depictions are spontaneous and full of life.

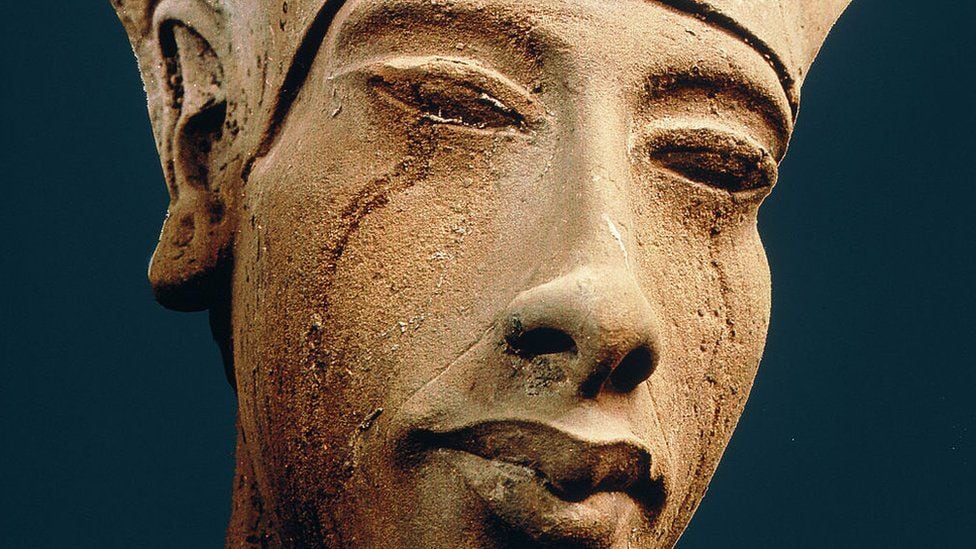

Not only that. His physiognomy is completely different to that of the pharaohs that came before and after.

Usually, the pharaohs were depicted in such a way as to appear conventionally handsome, strong, and manly.

Akhenaten, by contrast, has a stretched-out face, with an elongated nose that points to his pointed chin.

Her unusual full lips echo the feminine sensuality of her wide hips, while her unflattering tummy hangs over her belt.

It is an astonishingly expressionistic piece of sacred art.

religious persecution

Akhenaten had managed to establish a new city, a religious paradise in the desert. But everything began to collapse.

His subjects, even those who lived in his city, had not really abandoned the other gods, and Pharaoh learned of the betrayal.

He ordered to find all the images of the old gods and destroy them, especially those of the king of all kings, Amun-Ra.

Pharaoh became intolerant. He sent his soldiers to erase the memory of the gods in all his lands. Late in his reign, his revolution turned sour.

Also, because he refused to leave his beloved city, he was seen as weak and the country vulnerable to invasion.

Clay tablets found at Amarna reveal the nature of the problem.

One of them is from the ruler of one of Akhenaten’s vassal states, one of the protected neighboring countries.

He pleads with Pharaoh to send troops to help him hold off the Hittites, Egypt’s arch-enemies.

“I asked him but he did not answer me. He has not sent me the help I need,” complains the desperate ruler, in vain, since Akhenaten never sent the help and the State fell into the hands of the Hittites.

He had the army too busy chasing gods, even as Egypt lost territory, power, possessions, and its status in the world.

That was very serious. It was then that he suffered personal tragedies.

plague and death

The family drama is engraved on the walls of Akhenaten’s tomb.

Although badly damaged, a mourning scene can be seen. One of the princesses (she had six daughters with Nefertiti) died and her parents appear crying.

That’s something without precedents: Royal families never publicly showed emotions.

There is also evidence indicating that Akhenaten lost more than one daughter, probably victims of the plague, which was ravaging the country at that time.

Such an epidemic could kill 40% of the population and, as he was the pharaoh, Akhenaten was held personally responsible for the misfortune.

It was obvious to his subjects that the catastrophe was due to the fact that he had offended the old gods.

When it seemed that the situation could not be worse, he lost the woman who accompanied him from the beginning: Queen Nefertiti.

Akhenaten’s paradise was on the brink of collapse. For his advisers and courtiers of his certainty he was a dangerous liability. The country was losing its wealth and power.

13 years after the founding of his city, Akhenaten died.

There are those who believe that he was assassinated so that his reign would end.

The city was abandoned and later systematically destroyed, erased from memory, along with the cult of the Aten and Akhenaten himself, who for a long time was only remembered for being, probably, the father of Tutankhaten, who would have been the son of another of their wives, the enigmatic Kiya.

Restoration

plague and death

The family drama is engraved on the walls of Akhenaten’s tomb.

Although badly damaged, a mourning scene can be seen. One of the princesses (she had six daughters with Nefertiti) died and her parents appear crying.

That’s something without precedents: Royal families never publicly showed emotions.

There is also evidence indicating that Akhenaten lost more than one daughter, probably victims of the plague, which was ravaging the country at that time.

Such an epidemic could kill 40% of the population and, as he was the pharaoh, Akhenaten was held personally responsible for the misfortune.

It was obvious to his subjects that the catastrophe was due to the fact that he had offended the old gods.

When it seemed that the situation could not be worse, he lost the woman who accompanied him from the beginning: Queen Nefertiti.

Akhenaten’s paradise was on the brink of collapse. For his advisers and courtiers of his certainty he was a dangerous liability. The country was losing its wealth and power.

13 years after the founding of his city, Akhenaten died.

There are those who believe that he was assassinated so that his reign would end.

The city was abandoned and later systematically destroyed, erased from memory, along with the cult of the Aten and Akhenaten himself, who for a long time was only remembered for being, probably, the father of Tutankhaten, who would have been the son of another of their wives, the enigmatic Kiya.

Restoration

Tutankhaten’s paternity, indicates the Encyclopedia Britannica, is uncertain, although a document from Akhetaten “names him the king’s son in a context similar to that of Akhetaten’s princesses.”

What we know for sure is that the young pharaoh married his ancestor’s third daughter and that in his third year of reign he left the new capital and transferred the seat of power to Memphis, near present-day Cairo.

He rescued the old gods and restored Egypt to power and prosperity. But with the name of Tutankhamun. Amun was coming back. Aton, like the sun disk at sunset, was leaving.

The priests returned, more powerful than ever. And life returned to normal.

No Egyptian pharaoh ever tried to change the established order or challenge the gods.

Those who came after Akhenaten strove to destroy any trace of him and his heretical cult.

Their statues were torn down and, to strip them of meaning, the stones of their temples used as building material for new ones.

Those carved rocks were hidden so that no one would see them again.

The irony is that this preserved them for posterity: in the 1920s they began to emerge and much of what we know of Akhenaten and the cult of the Aten comes from them.

Tutankhamen died unexpectedly at the age of 19.

Source: Elcomercio

I am Jack Morton and I work in 24 News Recorder. I mostly cover world news and I have also authored 24 news recorder. I find this work highly interesting and it allows me to keep up with current events happening around the world.

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/GE3TCMZNGAYS2MJUKQYDAORRG4.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/MZ6ZVZ5AVFE2FG6NGQ4LHNNLCY.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/QJZHXZSQHNGRTLHDEOLHKOZCIY.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/EW4LPDTVSZD7DJDFQUSYGGNGT4.jpg)