To the sound of accordions and trumpets, the ballad “En preparación”, sung by Gerardo Ortiz, born in California (USA), could be mistaken for a cheerful polka. But his lyrics are chilling and brutal.

“If you’re not good enough to kill,” Ortiz shouts, “you’re good enough to be killed.”

Look: Thomas Lee, renowned billionaire, found dead in his office

The song goes on to describe a combat-ready gunslinger with a penchant for pickup trucks and his AK-47, and who goes by a “respected” code name: M1.

The man you are referring to is not a fictional character. “M1” was the code name of a notorious Sinaloa cartel drug trafficker, Manuel Torres Félix, alias “el Loco,” who was killed in a shootout with Mexican soldiers in 2012.

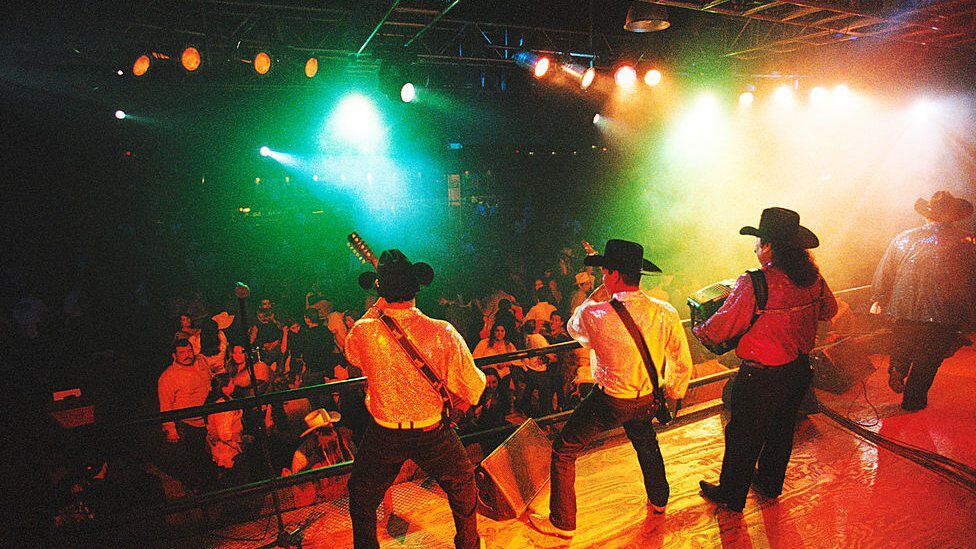

M1 may be dead, but his infamy and that of other gang members past and present, lives on in narcocorridoswhich can be heard everywhere from small town fairs to nightclubs across Mexico.

Old style with today’s headlines

This music draws on a deep tradition that dates back to the Mexican Revolution, but with a language and action whose spirit is straight from today’s headlines.

It is not surprising, then, that in the midst of the grim reality that is behind the long and, for now, lost battle against the violence of the cartelsthis musical genre divides the opinions of listeners in Mexico, as well as new audiences north of the border.

Although the style of narcorridos dates back at least to the turn of the last century, the genre first became popular in the United States in the 1980s, and there it has often been compared to the gangster rap tradition.

The first impulse he had in the United States was largely due to Chalino Sánchez, a Mexican migrant who is still popularly known as “the king of the narcocorridos”.

In many ways, Sánchez’s life was as violent as the themes of his music.

In 1992 he narrowly escaped death after being shot twice in a shootout during a concert in California. Four months later, he was kidnapped and finally he was killed just hours after receiving a threatening note while on stage at a concert in Mexico.

In the decades since his death, the genre he popularized has remained an appeal to many Mexicans and Mexican-Americans living in the United States, where he has a devoted following.

“I like music to tell real stories from real people,” says Alex Fernández, a first-generation American living in Southern California, just a few miles from the Mexican border. “People like crime movies or gangster rap. It’s the same thing.”

Reliable numbers of narcocorrido listeners in the United States are hard to come by, but the potential audience is in the millions. Mexican “regional music,” the broad genre that corridos fall under, is the strongest performing format among Hispanic radio consumers, according to Nielsen.

The audience among listeners on online platforms is potentially even larger. Spotify notes that the volume of streams for the genre has more than doubled since 2019 to reach 5.6 billion, 21% of which are from the United States.

Fernández details that among the songs currently on his corrido playlist is “30 armored,” a song about a convoy of trucks that works at the behest of Mexico’s Sinaloa cartel.

Another song, “I am the Mouse”, is sung from the perspective of Ovidio Guzmán López, son of Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán, whose arrest in January led to a series of fierce shootings and dozens of deaths.

“I don’t know fear”, says the song. “A Guzmán cannot be intimidated, especially by the government.”

Content in this genre is often inspired by real people and events, and has caused its radio broadcast or some live performances were recently banned in some parts of Mexico and in events that are considered potentially related to drug trafficking.

In November, the organizers of a week-long cattle festival in the Mexican state of Sinaloa, riddled with violence, they announced that corridos were prohibited because they promote bloodshed.

But for many American listeners, the content of the music, which often portrays drug dealers as anti-government Robin Hood-like figures, is part of the appeal.

Its popularity in the United States is directly comparable to the rise of gangster rap in the mid-1980s, according to Rafael Acosta, a professor at the University of Kansas who has studied the genre of narcocorridos.

“Gangster rap has become naturalized into mainstream culture, and it’s not much different in function and style,” he says.

The narcocorridos tell the stories of “people who feel, often with good reason, that they are neglected by the state and economic apparatuses, and they look for possibilities of rebellion and socioeconomic advancement,” says Professor Acosta.

And he compares them to movies and songs about Italian gangsters from the early 20th century or outlaws who smuggled moonshine during the Prohibition era of the 1920s.

A reaction?

But critics denouncing the genre point to its relationship to real-life violent incidents and the perceived relationship between musicians and criminals.

More than a dozen narcocorrido singers have been killed in Mexico in recent years, while others have been accused by authorities of involvement in crimes.

The violent nature of music is a “complicated” issue, even for fans, remarks Professor Acosta.

For some, there are even signs of the fatigue that drug-related violence in Mexico has generated. And that has turned some fans away from the music.

Howard Campbell, a professor at the University of Texas at El Paso, researches drug trafficking and culture on the US-Mexico border, and found that the popularity of music in the region has declined.

This trend is due in part to the fact that many in El Paso they have grown tired of the images of a drug war that has claimed thousands of lives across the borderhe argues.

“How many times can you show the same videos of drug traffickers, of people drinking champagne with women and guns? At a certain point it becomes stale and starts to lose its chic and cool aspects.. The reality is that it’s a horrible situation.”

“It’s something that will never completely go away,” he continues. “But I don’t think it will recover the significance it once had.”

Source: Elcomercio

I am Jack Morton and I work in 24 News Recorder. I mostly cover world news and I have also authored 24 news recorder. I find this work highly interesting and it allows me to keep up with current events happening around the world.

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/GE2TEMRNGAZC2MRUKQYDAORRGU.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/5XVZ7WGE4FB7TDRH3DESBISBRA.jpg)