The privileged geographical location Panama determined its history and, in fact, that of Colombia.

The two countries were one at the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century, when Panamanian territory began to be highly coveted.

LOOK: Who was Isaac Rabin and why his assassination was a serious blow to the peace process between Israelis and Palestinians

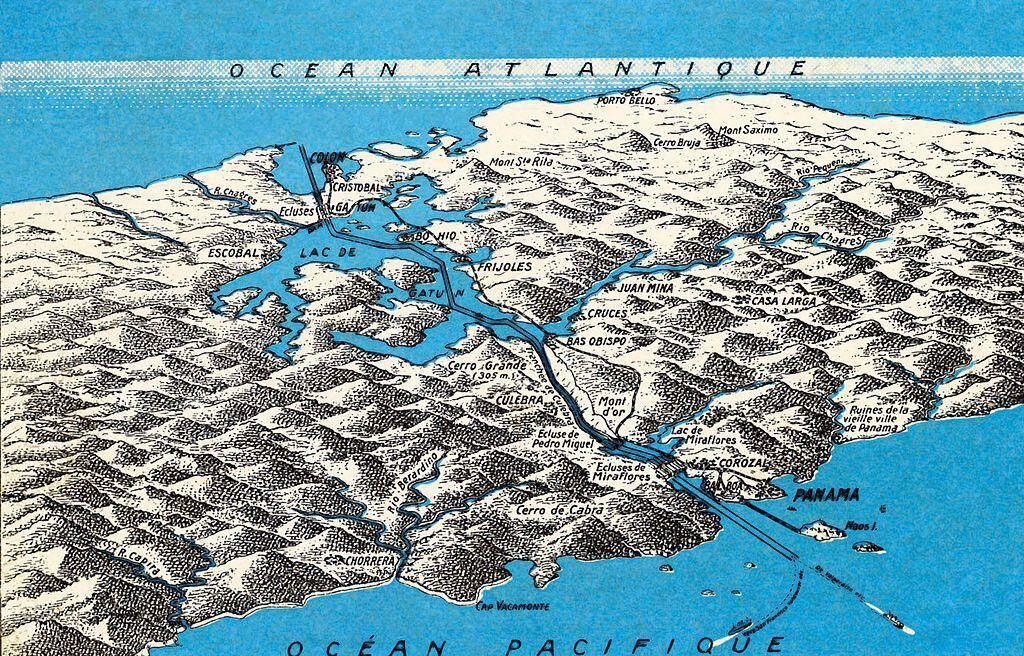

Its attraction was its access to the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, as it would allow it to house what, at that time, was a canal project that promised to be a great engineering work that would change the world market.

At that time there was a kind of international bid for Panama, in which Colombia, despite having several advantages, ended up losing. What was their territory became a dense border through which today a massive migration to the north of the American continent passes.

But how did this separation between Panama and Colombia occur?

At BBC Mundo we review history to understand how a bloody war, a revolutionary idea and a complicated treaty led Panama to stop being part of Colombia 120 years ago.

Panama in Colombia

In the 19th century and after independence from Spain, Gran Colombia was created. A country that included part of what is now Ecuador, Venezuela, Panama and Colombia.

Then, in 1830, Venezuela and Ecuador separated from that Greater Colombia and the country was renamed New Granada and, later, Colombia.

Between 1850 and 1880, Colombia was a federal country, which guaranteed religious freedom and based its political and administrative organization on the immense cultural and economic diversity of its territory, which included Panama.

“Panama was very important for Colombia and received considerable attention from the central government. Panamanians also played an important role in Colombian history. They were even presidents”, explained Panamanian historian Marixa Lasso to BBC Mundo.

However, at the end of the 19th century, a conservative party came to power that imposed a centralized state model, created a close connection with the Catholic Church and defended the legacy of the Spanish colonizers.

This period is known as Regeneration and gave way, in 1886, to a highly questioned Constitution.

The main objection is that it weakened the power of the nine Sovereign States that made up the country, since they became political-administrative entities dependent on the central government in Bogotá, the capital.

One of these entities was the Isthmus of Panama, that geographic feature located between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans, which also did not align with conservative hegemony.

“Panama played a leading role in the history of Colombian federalism. Panamanians had a great federalist and autonomist vocation and resented the Colombian centralist governments”, explains Lasso, author of the book Lost Stories of the Panama Canal.

And it was this political tension, which spread throughout Colombia, that served as a prelude to a civil war that would later facilitate international interference.

War

In Colombia, the two traditional political parties, the liberal and the conservative, have historically clashed very violently.

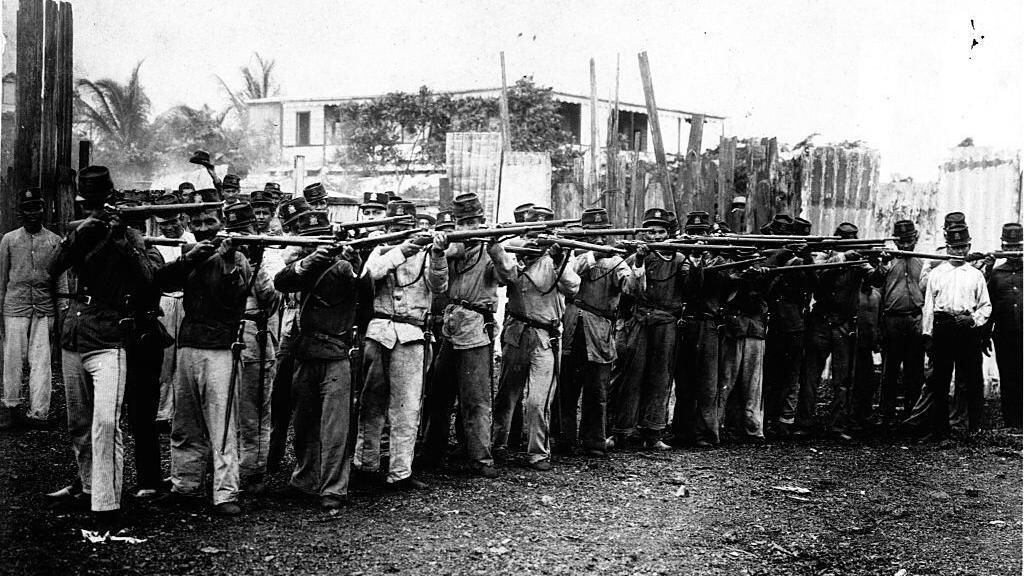

But perhaps the most emblematic confrontation was the war that took place between 1899 and 1902 and is known as the War of a Thousand Days.

There were three years of bloody battles that occurred as a result of the reaction of conservatives and moderate liberals who opposed Regeneration and the Constitution of 86, considering it authoritarian.

A perception shared by Panamanians. “Panama had a mostly liberal population. And at the end of the 19th century there was enormous fatigue with the conservative centralism of the 1886 Constitution”, explains Lasso.

In the end, the conservatives won the war and what is known as conservative hegemony began.

“The end of the war with the official victory of the conservatives and the judicial assassination of the liberal general Victoriano Lorenzo, who was an indigenous Panamanian, only increased discontent among the liberal majorities”, says Lasso.

Added to this was the fact that the outcome of the war was disastrous. 3% of the population died, infrastructure and industry were destroyed, inflation and external debt soared; and thousands of people left the cities.

At that moment in history it was clear that the unity of a country centralized by a Bogotá elite was quite fragile.

Therefore, any attempt to separate either region could have a chance of success.

The idea of uniting the oceans

It is in this context of political and post-war tension that the visionary idea of crossing the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific through Central American territory materialized.

But it’s not that this hasn’t been thought of before. Since the Colony, there have been projects that sought to unite the oceans.

At the end of the 19th century, railways already existed, but at that time the industrial revolution was in full expansion and the great capitalist powers such as the United Kingdom, France and the United States began to exert pressure to connect the oceans.

This canal project represented the crown jewel because it would allow whoever managed it to control a route that would transform world trade.

The first big bet occurred in 1880, when Bogotá granted the concession for the construction of the canal to engineer Fernando de Lesseps, a Frenchman who had just built the Suez Canal in Egypt.

But the illnesses of the workers, many of them African slaves, the humidity of the territory and the constant rains led the French project to bankruptcy.

And that is where the United States’ interest in this maritime route comes together with the Colombian State’s difficulty in controlling its territory.

Even more so when one of its regions, Panama, was separated from the administrative center by an immense and impassable jungle complex called the Darién Gap.

The role of the United States

At that time, the United States was an emerging power that had just gained control of Puerto Rico and Cuba and knew how to interpret the Colombian internal crisis as its great opportunity.

The North American country proposed to pay US$40 million maintain the concession for the construction of the canal.

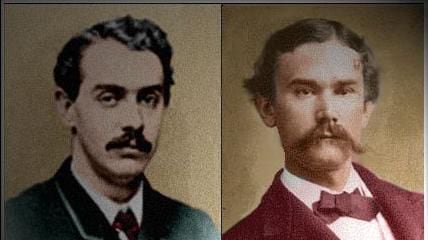

This agreement materialized with the treaty Herrán-Hay between Colombia and the USA, which established the guidelines for the concession and which was agreed between the US Secretary of State, John Hay, and the Colombian minister Tomás Herrán.

It was a complex negotiation in which they also contemplated the construction of the canal in Nicaragua, but had to take into account the French who made an initial investment in Panama.

Thus, it was finally decided that the canal would be built in Panama with North American capital, which in turn would pay Colombia and the French company.

But on August 5, 1903, the Colombian government, after Congress opposed several points of the treaty on the grounds that it violated the country’s sovereignty, announced that it rejected it.

This last decision by Colombia ended up giving way to Panama’s separation.

“When Colombia rejects the Herrán-Hay treaty, and there were good reasons to reject it, several factors combine in favor of Panama’s independence from Colombia,” says Lasso.

On the one hand, explains the historian, the Panamanians were emerging from the crisis caused by the War of a Thousand Days and the canal was seen as a salvation for their internal problems.

On the other hand, there was great discontent in Panama with the conservative government and the liberal defeat in the war.

Finally, the United States found in this Panamanian discontent “an excellent opportunity to obtain the treaty they desired without the interference of Colombia.”

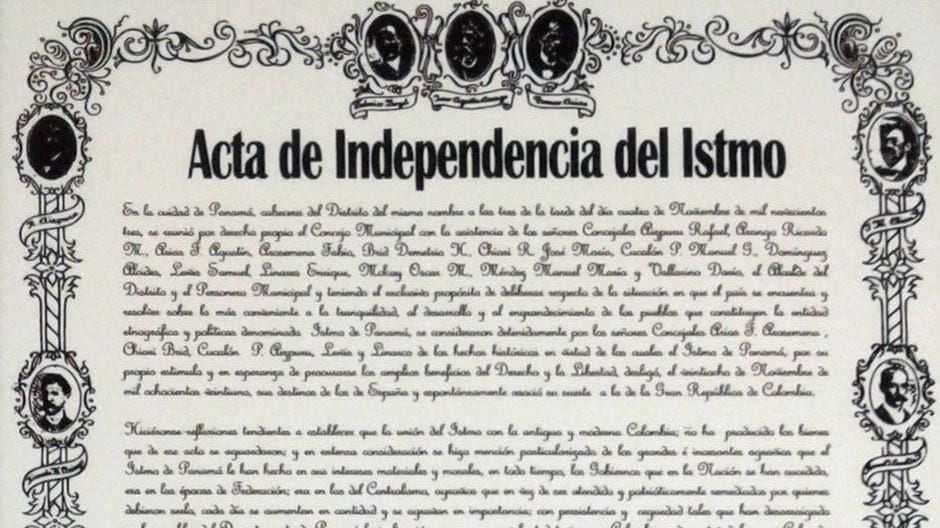

And it was then that Panama ignored the rejection of the treaty and, in alliance with the United States, which said it would intervene if there was military retaliation from Colombia, declared its independence on November 3, 1903.

“That day, eight North American warships were stationed in the Atlantic and Pacific oceans under the orders of Vice Admiral Coghlan and Admiral Glass”, describes Colombian historian Alfonso Múnera in his text Imaginary Frontiers.

And he cites the report of Colombian general Rafael Reyes to reconstruct the scenario. Múnera writes that Reyes “could not set foot in Panama and, worried, wrote to the president advising him to be very cautious, to prevent 40 North American warships from taking, in addition to Panama, the cities of Medellín and Cali.” .

11 years later, in 1914, Colombia agreed with the US to recognize Panama and resolved territorial and border disputes. This in exchange for compensation of US$25 million.

Today, more than a century later, this is a story in which the role played by the United States continues to be a source of debate.

Apparently, the more importance is given to this country’s role, the less heroic Panama’s independence appears.

“The Panamanians emphasized their role in this separation. Although the role played by the United States is recognized, it is important to remember that independence in 1903 was the last attempt in a long list of separatist attempts that occurred throughout the 19th century and that Panama had an autonomous vocation throughout that century and federalist basis. in the particularities of its history and geographical position”, concludes Lasso.

Source: Elcomercio

I am Jack Morton and I work in 24 News Recorder. I mostly cover world news and I have also authored 24 news recorder. I find this work highly interesting and it allows me to keep up with current events happening around the world.

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/XNKVZM6R3RDSRLI6VHDPBV64FA.png)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/AM2CXIHSBJHKTDVSRPD6LUJFX4.jpg)