:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/RMQDA44MGJDJLPXFD7RZWB3EEQ.jpg)

The knight pulls his arm back, ready to attack.

He is dressed in typical 14th century armor, with chainmail, a belted tunic and a bucket helmet. Standing in a small grassy clearing, he holds a shield that, inexplicably, has a face of its own. He also wields a club that grazes the bottom line of a religious text, all on the yellowed page of the medieval book in which it is drawn.

LOOK: “I couldn’t protect my girl. I just wanted to give her a decent life”: the father who saw his daughter suffocate while trying to reach the UK

But even in the pages of ancient tomes, knights must face mortal dangers.

In the case of this knight in question, his opponent is a particularly elusive beast, an enemy who often appears skulking in the margins of books or engaging nobles in mortal combat. Sometimes these creatures appear to hover and attack knights in the air. Other times, there is more than one.

The giant warrior snail is an exclusively medieval phenomenon. And, to this day, why they were drawn and what they represented remains a mystery.

“This has created a lot of perplexity among art historians and bibliographers, who wonder what they mean,” says Kenneth Clarke, senior lecturer in medieval literature at the University of York in the United Kingdom.

A rare and expensive work of art

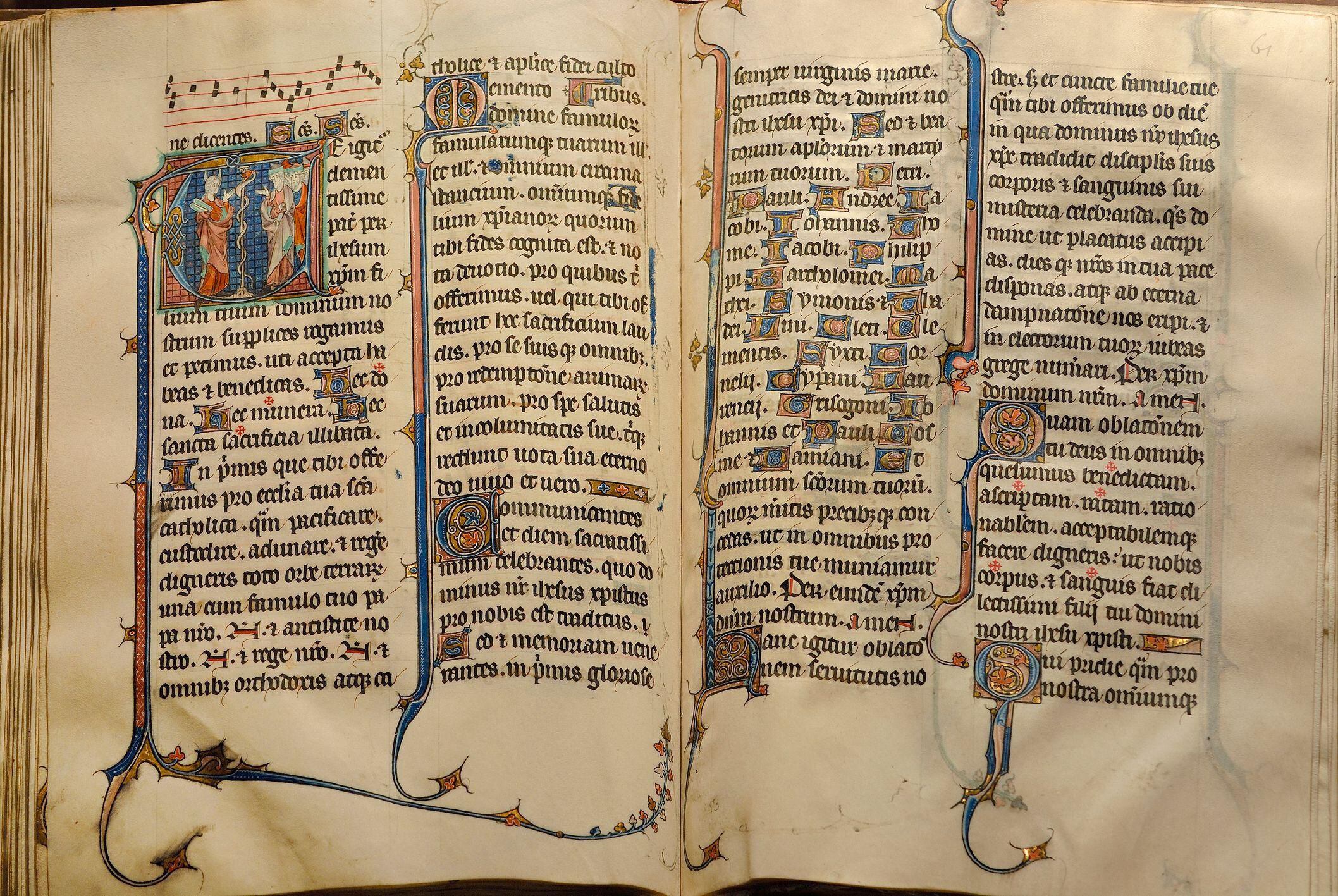

O marginalia These are the small works of art and illustrations found in the margins of book pages.

In the Middle Ages, Finished manuscripts that were more unique could be finished with an additional watermark: Intricate borders made of curly foliage, fantastical creatures and other assorted designs.

Sometimes they were added immediately, others were added decades later, but they were not a casual task. They were often painted with precious pigments, such as lapis lazuli, or highlighted with gold.

“They were very, very, very expensive books, with a very small audience,” says Clarke.

Ornaments are found in a wide variety of religious works, as the psalters, which are books for songs; the horarium or books of hours that contained prayers and psalms; breviaries for daily prayers; the pontifical, for the rituals carried out by the bishops and the decrees, which were books where papal letters or decisions were compiled.

They could be strange, naughty, grotesque and even rude drawingswith exposed buttocks, penises, medical conditions and a surprisingly large number of bloodthirsty rabbits adorning the pages of sobering devotional texts.

Often, the marginalia It appears to bear little relation to the accompanying text.

The obsession with snails

But for a brief period in the late 13th century, illuminators – those who decorated books – across Europe adopted a new obsession: fighting snails.

For a comprehensive study of these belligerent gastropods Art historian Lilian Randall counted 70 examples in 29 different books, most of which were printed between 1290 and 1310.

Illustrations are found throughout Europe, but especially in France, where there was a thriving manuscript production industry at the time, Clarke claims.

The specific scenarios in which the warrior snails found themselves varied, but generally followed the same format as an attacking snail facing a knight.

Mollusks often have their antennae—technically called upper tentacles or eye stalks—pointing aggressively forward, like swords.

In one of the illustrations, a snail fights a naked woman. In others they do not appear as normal molluscs, but as a hybrid between a snail and a man that serves as a mount for another animal: a rabbit, of course.

With time, The warrior snail meme began to spread to other places in the medieval world.like cathedrals, where they were carved into the facades or, as in one case, hidden behind a type of folding seat.

Why were they there?

“The fight between the snail and the knight is an example of the world turned upside down, a broader phenomenon that produced many different medieval images,” explains Marian Bleeke, professor of medieval art at the University of Chicago.

“The basic idea is the overturning of existing or expected hierarchies. It’s supposed to be surprising and even fun; I think today we understand that implicitly,” he says.

However, it is still unclear whether these drawings had deeper symbolic meanings beyond this change in status.

“The knight should be brave and strong, capable of defeating all enemies, but here he cowers in fear of a snail or is even defeated. What we don’t agree on is what to do and interpret from that point onwards”, says Bleeke.

Many interpretations have been proposed, including the idea that the snail fights They represent the struggle between the upper and lower classes or stage the resurrection.

A widespread idea is that the knights who face the snails personify cowardice and that their incorporation into religious texts may have been satire.

As Lilian Randall points out, in many snail scenes a knight appears kneeling praying before his slimy attacker or dropping his sword, and in others a woman appears begging the gallant fighter not to face such a deadly enemy.

Building on the cowardly knight theme, Randall suggests that the snail motif could have been a political critique in which the knights represented the LombardsGermanic people who established the so-called Lombard kingdom in present-day Italy until the end of the 8th century.

“The Lombards were presented as a group that collected taxes, but also practiced usury,” explains Clarke.

In medieval France – where most snail designs were made – the Lombards were slandered in various ways, for example by suggesting that they were unhygienic and cowardly.

Randall points out that in the 12th century this name became synonymous with ungentlemanly behavior in general. In popular legend, a Lombard peasant encountered a heavily armored snail that the gods encouraged him to face while his wife begged him not to be so reckless.

Clarke is skeptical of this idea, considering how common snail wars are in medieval books.

Bleeke explains that today’s historians are less likely to think that illustrations drawn in the margins have such simple meanings.

“I don’t think images work like that. I would like to see how the snail was represented, what it looked like and where it was located to be able to think about the meaning given to it in each specific case.”

But whether Randall is right or not, Bleeke believes they can teach us something important about how masculinity was viewed in the medieval world.

“The brave, strong knight is an ideal or idealized version of masculinity and the fight against the snails undermines that,” says Bleeke.

“For me, these images show us that gender has never been as stable or safe as some would like to believe. It has always been a place of contestation.”

Source: Elcomercio

I am Jack Morton and I work in 24 News Recorder. I mostly cover world news and I have also authored 24 news recorder. I find this work highly interesting and it allows me to keep up with current events happening around the world.