On June 17, 2007, school teacher Gustavo Moncayo decided to march from his town, in the far south of Colombiauntil Bogota to ask for the release of his son.

LOOK: The alleged Transmilenio rapist “should have been tried and sentenced in an exemplary manner,” says the victim’s lawyer

Ten years earlier, Pablo Emilio Moncayo, then a 19-year-old army corporal, was captured by the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) in an ambush that left 10 soldiers dead and 18 kidnapped.

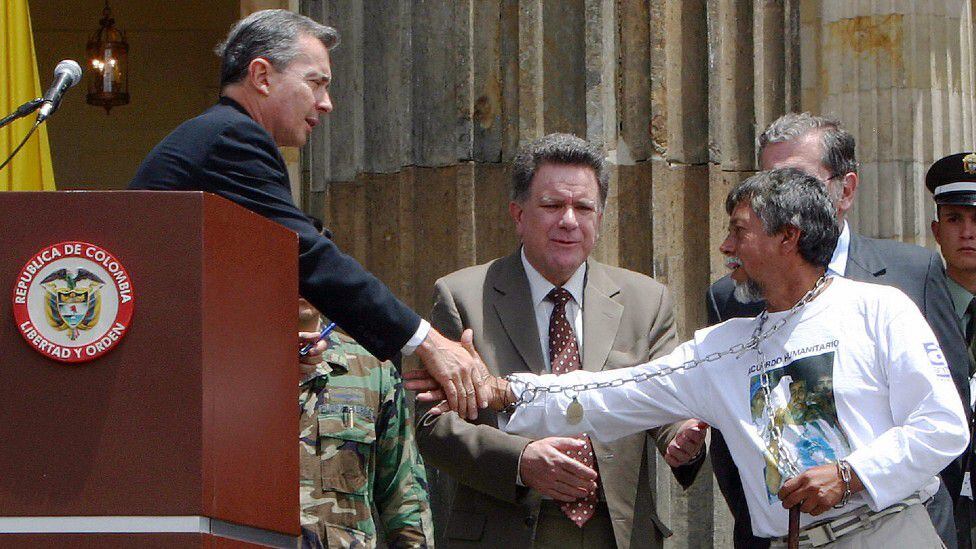

The desperate walk of “profe Moncayo”, with his hands tied by chains and a white T-shirt with a photo of his young son, moved the Colombians, who followed each step of the thousand kilometers of travel through the media.

The modest Geography professor, who after the so-called “walk for peace” met with presidents and organizations from all over the world, became a symbol of the pain that millions of Colombians suffered in those years, the worst of a 60-year war.

On Tuesday, Professor Moncayo died at the age of 69 from liver cancer.

After a few years living in Canada, where he took asylum due to threats, the professor returned to Colombia last year with the hope of receiving a transplant, being repaired by the now demobilized leaders of the FARC and participating in the trials that hope to find the truth about the conflict.

Moncayo could not fulfill his last tasks, but his memory as an example of reconciliation in a country traumatized by the kidnapping is what millions remembered this Tuesday.

“Don’t back down, don’t give up”

“Remembered mother… I think I’ve had more adventures than Indiana Jones and I think that if I made a film of what I experienced, he would be left in diapers,” wrote Pablo Emilio Moncayo in the first letter that his kidnappers allowed him to send to his family as proof of life.

Pablo Emilio is the eldest of five siblings who were born in Sandoná, a small peasant town in the mountains of Nariño, near the border with Ecuador. His mother, María Estela Cabrera, was a professor of Philosophy.

At 18 years old, Pablo Emilio wanted to go to university to study electronics. The few resources of his family prevented it. He chose to enter the army.

To his satisfaction, they sent him to the Patascoy communications base, also in Nariño, and just three months later, on March 21, 1997, the confrontation that left him in the hands of the guerrillas occurred.

In the aforementioned letter that he sent to his family, Pablo Emilio asked his parents “never back down, never give up” in search of their liberation. That they did.

From teacher to activist

Professor Moncayo began from that very day a feat that took him to dozens of countries and to the Vatican, as well as to the Casa de Nariño, where he met with all the presidents since 1998.

The 2007 march through the highways made him famous, not only because the media covered each mishap, but also because during those 46 days the conflict intensified, the FARC killed 11 deputies who were kidnapped, and the sensitivity of Colombians for that war crime increased.

Moncayo went from seeking his son’s release to being the face of a national and international campaign to end the war.

Despite his father’s insistence, Corporal Moncayo was one of the FARC’s longest-lived hostages: lasted 12 years in captivity.

A humanitarian agreement with the guerrillas brokered by then-Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez, Senator Piedad Córdoba and Brazilian President Lula da Silva allowed their release.

It was a massive event, of enormous media interest, during which Pablo Emilio removed from his father the chains that he had tied three years ago.

President Álvaro Uribe was a skeptic of negotiations with the guerrillas and a supporter of the iron hand. In addition, he had been involved in strong public disputes with Professor Moncayo, who advocated an agreed release.

Over time, the humble farmer in the remote south of the country became an activist of international reach. Uribe even lent himself to asking for the help of opponents like Chávez and Córdoba.

The insistence of Professor Moncayo turned the release of Pablo Emilio into a matter of State.

The Truth Commission estimates that Between 50,000 and 80,000 Colombians were victims of FARC kidnappings.

The campaign of “profe Moncayo”, as he is known in Colombia, managed to give visibility to all these victims. It was not only in the name of his son Pablo Emilio.

Source: Elcomercio

I am Jack Morton and I work in 24 News Recorder. I mostly cover world news and I have also authored 24 news recorder. I find this work highly interesting and it allows me to keep up with current events happening around the world.

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/GE4TEMBNGEYS2MJVKQYDAORRHE.jpg)