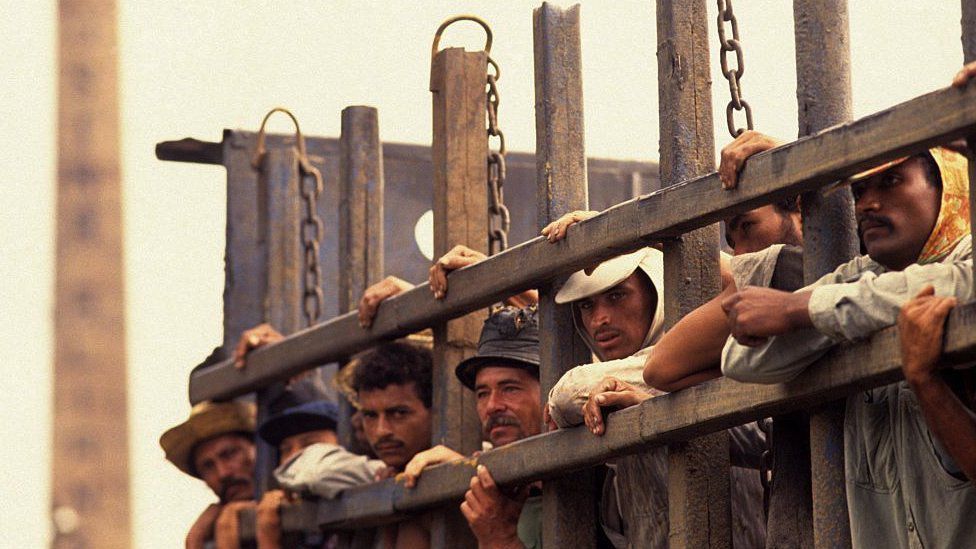

On February 22, police rescued more than 200 men from vineyards in the southern city of Bento Goncalves. Brazil.

The men had been used in forced labor and subjected to physical violence, as well as “degrading conditions”. But the “wine slave” scandal is far from being an isolated case of modern day slavery in that country.

Look: Cyclone Yaku: Brazil expresses its solidarity with the Peruvian people the effects of heavy rains

Despite a persistent cough, Neco* considered escaping to be free as he left the room he shared with 15 other colleagues to head to the vineyards for another grueling grape-picking session.

He thought he had enough energy left to do it, but he finally passed up the opportunity.

“I couldn’t leave behind the boys I had brought with me,” he told the BBC by phone from his home in the northeastern city of Salvador, still coughing.

Neco had helped round up 47 men and together they set out on the three-day, 3,000 km bus journey between Salvador and Bento Gonçalves, in the heart of Brazil’s wine country.

They had all been promised free room and board, and about $770 for two months of work, a decent wage in a country with a monthly minimum wage of $250.

But what seemed to be a good opportunity it soon turned to something much darker.

“As soon as we got there they sent us to work, with no time to rest. I immediately knew something was wrong,” Neco says.

Tasers and stun guns

Then came 15-hour shifts, little food, and bullying.

The guards who guarded the outside of workers’ dilapidated homes at night to prevent them from leaving also raided crowded rooms at dawn to take them to work.

Workers who doubted or complained, Neco says, They were threatened with beatings and electric gun discharges.

That’s why he kept going, even after a cold he caught while working in the rain turned into a nasty chest infection.

“They were carrying these electrical things that make sparks and were threatening to use them to shake us out of bed,” he explained.

“Some of the men were saying ‘they’ve been dying to use them on us’ and laughing.”

For Paulo*, another worker, the threats came true.

He told the BBC he was shocked twice by guards for ‘not getting up fast enough’.

“They said they would kill us if we made a big fuss about the beatings,” he says.

Both workers told the BBC they had seen bruises and scratches on colleagues who claimed to have been beaten by guards, although they did not witness the assaults.

Other workers told police that corporal punishment was common.

Neco, Paulo and the other 205 workers, all men between the ages of 18 and 54, were rescued by a group of law enforcement agencies on February 22 as victims of modern slavery.

They had been three weeks working from Sunday to Friday, without rest.

Workers made similar complaints to police, who confiscated stun guns and pepper spray cans during the raid.

The operation, which began after three workers fled the scene and alerted authorities, made national headlines after it was revealed that Servicios Fenix, the company that had brought Neco and his team to the vineyards, provided workers for three of the largest wine producers in Brazil: Aurora, Garibaldi and Salton.

The three companies issued statements denying knowledge of the exploitation and holding the contractor responsible.

Aurora went further, publishing an open letter apologizing to the rescued workers and the Brazilian people for what she called an “unforgivable episode.”

The three companies also pledged to review their supply chains.

Servicios Fenix issued a statement announcing that it was “investigating the allegations” and that it will take “all necessary steps to address any irregularities.”

The winemakers also announced on March 9 that they had reached an agreement with the Labor Ministry and agreed to pay the equivalent of US$1.4 million in fines, including compensation for exploited workers.

60,000 slaves

But the “wine slave scandal,” as the local press has dubbed it, is by no means a rare occurrence of modern slavery in Brazil.

Since 1995, the year in which the government officially admitted the existence of this type of practice in its territory, more than 60,000 people have been rescued from similar situations, according to figures from the Ministry of Labor.

Brazil is not the only country facing the problem: the International Labor Organization (ILO) estimated that 28 million people around the world were in forced labor in 2021.

Admar Fontes is the coordinator of a government agency against slavery in the state of Bahia, where 194 of the “wine slaves” came from.

He oversaw the operation to get them home and said the case stands out for more than just the number of exploited workers.

“Overall, the people who intimidated the workers displayed by far the most violent behavior I’ve come across in the 12 years I’ve tried forced labor cases.”

“The people responsible for hiring these workers acted boldly, as if they could treat the men horribly and get away with it,” he added.

The workers, Fontes notes, also reported hearing insults related to their origins from the northeast of the country: the poverty-stricken and drought-stricken region that has historically provided migrant labor to much of Brazil.

“All the men told me they were made fun of regularly.”

While Fontes points out that modern slavery is an old problem in Brazil, he suspects that people who exploit workers have been more encouraged to do so in recent years due to the economic downturn in Brazil, following the covid-19 pandemic. 19 and the war in Ukraine.

“When social vulnerability increases, people tend to get more desperate and accept any kind of job”he explained.

But Fontes also points to the far-right former president, Jair Bolsonaro, and the several times the former leader criticized legal efforts to curb modern slavery.

For example, a proposal to punish, with the confiscation of their assets, employers who use slave labor.

Fontes is not alone in that suspicion.

“Modern slavery in Brazil did not start with President Bolsonaro, but he played down the problem publicly,” Italvar Medina, the district attorney in Brazil’s Public Ministry overseeing the “wine slaves” case, told the BBC.

Racial and educational bias

Medina also noted that the Bolsonaro administration cut the budget for anti-slavery inspections, which have already been plagued by staff shortages in recent years.

“We depend on those inspections to stop the violations”.

Data from the Ministry of Labor show that only two sectors, livestock and sugarcane harvesting, were responsible for 45% of the cases of violations of workers’ rights between 1995 and 2022.

The exploited workers are often black or mixed race and the victims invariably have a low level of formal education, making them vulnerable to being lured with false promises of work. Most are men.

One exception is Taiane dos Santos, who at 17 found herself working on a Sao Paulo coffee plantation after being promised money that, as a new mom, she desperately needed to feed her baby.

Taiane endured 50 days of unpaid forced labor before being rescued in a raid in June 2021.

“I come from a small town where there is never enough work to go around, so people often travel to find temporary work,” he told the BBC.

“But no one ever told me that I could end up a prisoner.”

The experience led Taiane to help create an NGO in her city that works on education about the rights of temporary workers, helping them identify possible slave labor schemes.

“I don’t want anyone to go through that ever again,” he says.

slavery past

Journalist and political scientist Natalia Suzuki explains that the first line of defense against exploitation is crucial to protect workers.

He is in charge of a series of projects at the NGO Reporter Brasil that aim to train professionals such as social workers and teachers. to educate potential victims of modern slavery.

“Slave labor is entrenched in the productive sectors of Brazil and the general public is often desensitized to it,” explains Suzuki.

“We need to change this mentality, starting with those who could be victims of this type of practice.”

However, it is a difficult battle. Just five days before the “wine slave scandal” made headlines, a Labor Ministry inspection found 139 workers in modern slavery on a sugarcane farm in Goiás, in the central-western region of Brazil.

The number of people rescued per year is increasing: in 2022 alone, more than 2,500 people were rescued. According to the Ministry of Labor, it is the highest figure since 2013.

It is not uncommon for rescued workers to be drawn back into forced labor schemes if your financial situation does not improve.

Neco, for example, admits that he may have to travel far again in search of work, despite the trauma he experienced at Bento Goncalves.

“I have not had a regular job since the covid-19 pandemic and I need to feed my children,” she said.

Admar Fontes, who is in regular contact with Neco and the other rescued workers, fears that there is no shortage of offers from businessmen willing to exploit their desperation.

“The sad reality is that Brazil abolished slavery in 1888, but it has never ceased to exist in the country,” he says.

*The names of the workers have been changed at their request.

Source: Elcomercio

I am Jack Morton and I work in 24 News Recorder. I mostly cover world news and I have also authored 24 news recorder. I find this work highly interesting and it allows me to keep up with current events happening around the world.

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/GE2TCMZNGAZS2MJXKQYDAORRGU.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/OJARSJKXE5F7LOP6YA3OXWBC6A.png)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/EWKGXMRPDNC4ROA37QHEYP7D7M.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/CWZVXJ5QHZDXHFY4B43EENW5ZU.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/PV5GHT3BLRBTRDXGKMULPWZRGU.jpg)