When talking about countries that are in fashion, it can be said that Vietnam It’s definitely getting a lot of attention.

Known in the past to be silently hidden in the strategic shadows, with a leadership almost unknown to the rest of the world, Vietnam is now wooed by all.

WATCH: How NATO and its new members prepare to face a potential threat from Russia

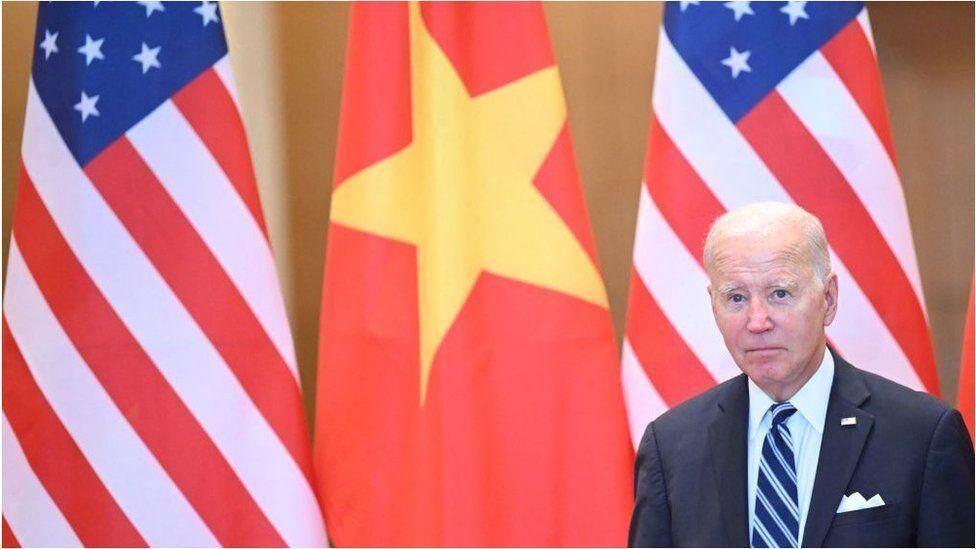

Both US President Joe Biden and China’s leader Xi Jinping visited the country last year.

The US has raised its relationship with Vietnam to the highest possible level, that of “extensive strategic partner”.

Vietnam has agreed to enter into 18 existing or planned free trade agreements.

Your collaboration is necessary on issues of climate change, supply chain resilience or pandemic preparedness, among others.

The country is seen as a vital regional player in the growing rivalry between China and the US; in the South China Sea, where claims to a group of islands are disputed; and as the best alternative to China for contract manufacturing.

But what has not changed is the iron grip with which the Communist Party maintains power and controls all forms of political expression.

Suspicion of external influence

Vietnam is one of the five remaining communist and one-party countries in the world.

No political opposition is allowed. Dissidents are regularly arrested and repression has become even harsher in recent years.

Political decisions at the highest levels of the party are shrouded in secrecy.

However, an internal document leaked a few weeks ago from the Politburo of the Central CommitteeVietnam’s highest legislative body, gave an idea of what the party’s top leaders think about all these ties with international partners.

The document, known as Directive 24, was obtained by Project88, a human rights organization focused on Vietnam. References to it in several party publications suggest it is genuine.

It was issued by the Politburo last July and contains stark warnings about the threat to national security from “hostile and reactionary forces” introduced into Vietnam through its growing international ties.

According to Directive 24, they will “increase their activities of sabotage and internal political transformation… forming alliances and networks with ‘civil society’, ‘independent trade unions’, creating the case for the formation of internal political opposition groups .”

The document urges party officials at all levels to be rigorous in their defense against these influences..

It warns that, despite all of Vietnam’s apparent economic successes, “economic security, finances, currency, foreign investment, energy, employment” are not strong and there is a latent risk of external dependence, manipulation and certain “areas”. “confidential.”

These are alarmist words.

In none of its public statements has the Vietnamese government appeared so insecure.

What does this mean then?

Greater surveillance

Ben Swanton, co-director of Project88, has no doubt that Directive 24 foresees the beginning of an even more severe campaign against activists human rights and civil society groups.

It cites nine orders that the document ends up giving to party leaders, including monitoring social media to combat “false propaganda”, “not allowing the formation of independent political organizations” and being attentive to people who take advantage of increasing contact with institutions international. provoke “color revolutions” and “street revolutions”.

“They took the mask off,” says Ben Swanton. ““Vietnam’s leaders are communicating that they intend to violate human rights as a political issue.”.

Not everyone agrees with this interpretation.

“Directive 24 is not so much a sign of a new wave of domestic repression against civil society and pro-democracy activists, but more of the same. In other words, the continued repression of these activists”, says Carlyle Thayer, professor emeritus of Politics. from the University of New South Wales, Australia, and a renowned expert on Vietnam.

Thayer points to the timing of the directive’s release, just after the US and Vietnam agreed to a high-level alliance, and just two months before President Biden’s visit.

It was an important decision, he says, driven by the party’s fear that the impact of the Covid pandemic and the economic slowdown in China could prevent Vietnam from achieving its goal of being a developed, high-income country by 2045.

It needed closer ties with the US to take its growing economy to the next level..

Hard-line elements within the party fear that the US will inevitably encourage pro-democratic sentiment in Vietnam and threaten the party’s monopoly on power.

Thayer believes the combative language used in Directive 24 is intended to reassure hardliners that this will not happen.

The professor thinks that the decision to have the personal signature of General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong, not only the most powerful political figure in Vietnam, but also a well-known communist ideologue, had this same intention.

The leaders’ dilemma

What Directive 24 clearly illustrates is the dilemma facing Vietnam’s communist leaders. as your country becomes a global power in production and trade.

Vietnam is not big enough to do what China did: hermetically isolate itself within its own “great firewall”.

Social media platforms like Facebook are easily accessible there. Vietnam needs foreign investment and technology to continue to grow rapidly and cannot afford to shut down.

Some of the free trade agreements Vietnam has committed to, such as the one it struck with the EU in 2020, come with human and labor rights clauses included.

Vietnam has also ratified some of the International Labor Organization (ILO) conventions, although not the one requiring freedom of assembly.

But Directive 24 suggests a reluctance to respect such clauses.

In it, the party demands explicit limits on how independent unions can operate, ordering their leaders to “strictly guide the establishment of labor organizations; take initiatives by participating in ILO conventions that protect freedom of association and the right to organize.” ensure the continuity of party leadership, party cell leadership and government administration at all levels”.

In other words, a “yes” to cooperation with the ILO and a firm “no” to any union that is not controlled by the party.

Ben Swanton argues that Directive 24 signals to Vietnam’s potential Western partners that its agreements on human and labor rights are nothing more than a fig leaf, timidly covering up the agreements they have made with a political system incapable of respecting individual rights.

And the question is: which civil society groups will be allowed to monitor these free trade agreements, when Six environmental and climate activists have already been arrested under false pretenses at the same time that Vietnam had just signed a huge energy transition alliance with Western governments?

There was a time, several decades ago, when there were those who thought that one-party Marxist-Leninist states were the future, that they would bring modernity, progress and economic justice to the world’s poorest societies.

Today, however, they are a historical anomaly.

Until China is the political model of very fewdespite the admiration aroused by its economic successes.

Vietnam’s leaders hope to achieve something akin to a magic trick: maintaining the tight control they have long exercised over the lives of their people while exposing them to ideas and inspiration from abroad in the hope that they can maintain the expanding economy.

Source: Elcomercio

I am Jack Morton and I work in 24 News Recorder. I mostly cover world news and I have also authored 24 news recorder. I find this work highly interesting and it allows me to keep up with current events happening around the world.

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/RZOG5VKHQVDGJPMHIGO6K4OLSU.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/LV7OMATAAJGGLBKBXVM4P37XMQ.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/TICWSMXVBJCX5PQHSMOJPEONRY.jpg)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/XX7FN3AZSNFNHOF24BXPDKTYAE.jpg)