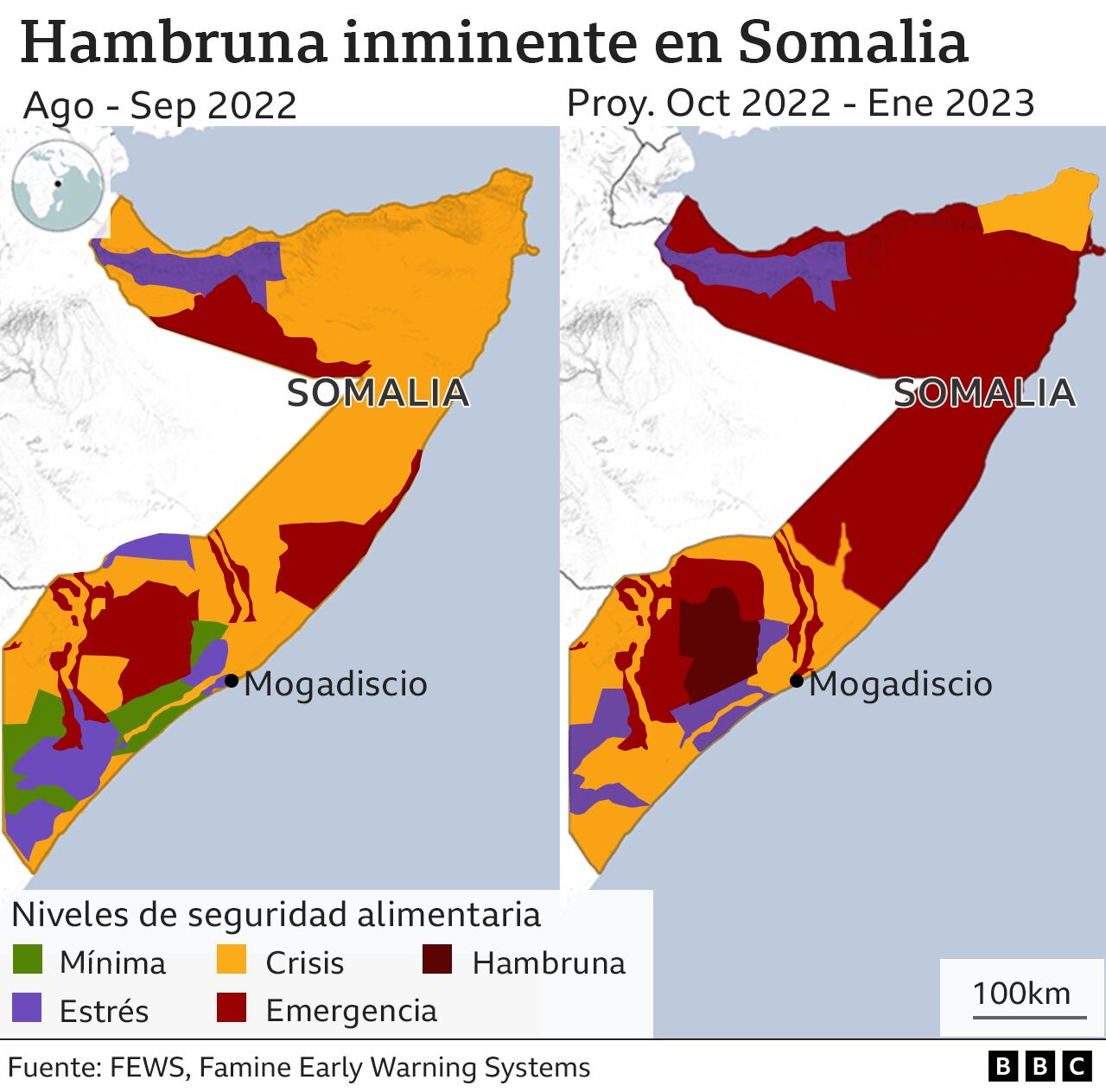

More and more children are dying in Somalia in the midst of the worst drought to hit the country in 40 years. Government officials say an even bigger catastrophe could strike within days or weeks unless more help arrives.

Tears streamed down Dahir’s 11-year-old cheeks sunken from hunger.

LOOK: Rats, Bones, and Mud: The Foods of Hunger That Desperate People Eat to Survive

“I just want to survive this,” he said quietly.

Sitting next to the family’s makeshift tent on the dusty plain outside the town of Baidoa, his exhausted mother, Fatuma Omar, told him not to cry.

“Your tears will not bring your brother back. Everything will be fine,” he said.

Fatuma’s second son, Salat, 10, starved to death two weeks agoshortly after the family arrived in Baidoa from their village, after walking for three days.

Salat’s body is buried in rocky soil a few meters from his new home. The grave is already littered and increasingly difficult to spot as newly arrived families camp around it.

“I can’t grieve for my son. There is no time. I need to find work and food to keep others aliveFatuma said, as she cradled her youngest daughter, Bille, nine months old, and turned to look at her six-year-old daughter, Mariam, who had a hacking cough.

Across the dirt road that turns southeast toward the coast and Somalia’s capital, Mogadishu, other displaced families told grim stories of long treks through a landscape of drought-torn land in search of food.

“I didn’t have the strength to bury my daughter”

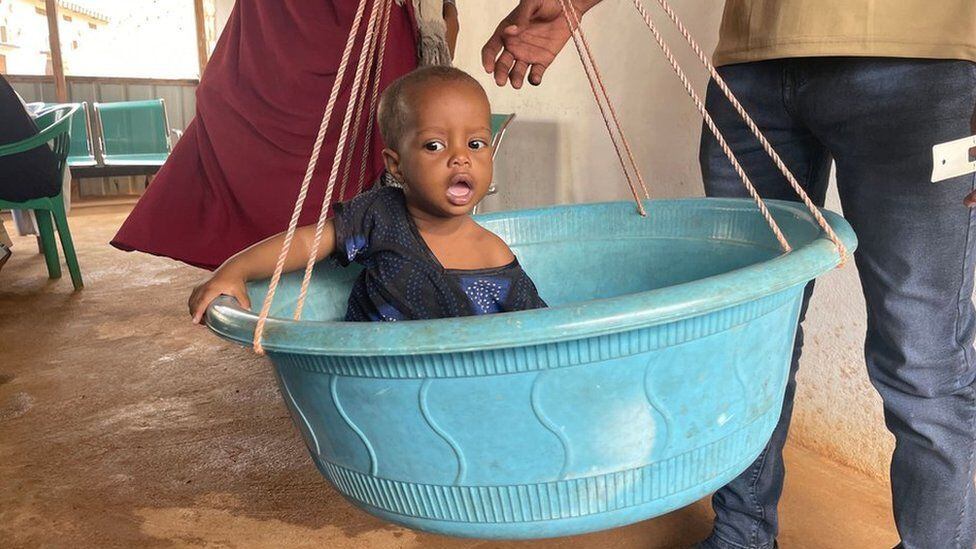

A survey showed that nearly two-thirds of young children and pregnant women in the camps suffer from acute malnutrition, which, coupled with a high mortality rate, would indicate that a famine should have been declared locally.

“I saw my daughter (Farhir, three years old) die before me and I couldn’t do anything,” said Fatuma, who walked for at least 15 days with her nine children from a town called Buulo Ciir to reach Baidoa.

“I carried her in my arms for 10 days. We had to leave it on the side of the road. He didn’t have the strength to bury her. We could hear the hyenas getting closer,” he continued.

“I didn’t bring anything with me. There is nothing left at home. The cattle are dead. The fields are dry,” added Habiba Mohamud, 50, clutching a piece of rope in one hand and acknowledging that he will never return to his village.

A succession of droughts, intensified by climate changenow threaten to end a pastoral way of life that has endured for centuries in the Horn of Africa.

Like other newcomers, Habiba was busy trying to pitch a tent for her family out of sticks, twigs, scrap cardboard and plastic sheeting, hoping to finish it before the cold night. Only after finishing was she able to dedicate herself to finding food and medical help for some of her children.

In the admissions room of the city’s main hospital, Dr. Abdullahi Yussuf moved from bed to bed, examining his tiny, emaciated patients. Most were children between two months and three years.

They were all severely malnourished. Some had pneumonia and many were also battling a new outbreak of measles.

Few babies had the strength to cry. Several had badly damaged skin, broken by the swelling that sometimes accompanies the most extreme cases of starvation.

“Many die before even reaching the hospitalsaid Dr. Abdullahi, as he watched his team struggle to connect an IV tube to the arm of a groaning two-year-old.

“It’s scary, people are dying”

Although Somali officials and international organizations have warned for months of impending famine in this region of southwestern Somalia, Abdullahi said his hospital had long been short of basic items, including nutritional supplements for children.

“Sometimes we are short of supplies. In fact, it’s scary because people are dying and we can’t help them. Our local government is not handling this well. You haven’t been planning for the drought or for the arrival of displaced families,” the doctor said with visible frustration.

A local government minister admitted there were flaws.

“We need to be faster, we need to be precise… and more effective,” said Nasir Arush, Minister for Humanitarian Affairs of the South West state, during a brief visit to one of the camps around Baidoa.

But the minister insisted that receiving more international support is key.

“If we don’t get the help we need, hundreds of thousands of people will die.. What we are doing now we should have done three months ago. Unless help comes quickly, I think something catastrophic is going to happen in this area,” Arush said.

The process of formally declaring a famine can be complicated. It depends on data that is difficult to obtain accurately and often on political considerations.

The UK’s ambassador to Mogadishu, Kate Foster, described the formal declaration of famine as “essentially a technical process”. Foster pointed out that during the 2011 drought “half of the 260,000 recorded deaths occurred before famine was declared”.

Abdirahman Abdishakur, the presidential envoy leading Somalia’s international effort to raise more funds, particularly thanked the US government for recent donations that he said “have given hope.”

But Abdishakur warned that without more help, what is now a localized crisis in one part of Somalia could quickly spiral out of control.

“We had been sounding the alarm… but the international community’s response was not adequate,” Abdishakur said.

“A famine is projected. It’s already happening in some places in Somalia, but we can still prevent a catastrophic famine,” he said by phone during a stopover in Toronto, Canada.

Women flee, men stay behind

Although estimates vary, Baidoa’s population has quadrupled in recent months, to a total of nearly 800,000 people.

And any visitor will quickly notice a striking fact: Almost all of the adult newcomers are women.

Somalia is at war. The conflict has endured in different forms since the collapse of the central government three decades ago. and continues to affect almost every region of the country, ripping men from their families to fight for a series of armed groups.

Like most of those arriving in Baidoa, Hadija Abukar recently escaped from territory controlled by the Islamist militant group al-Shabab.

“Even now I get calls from the rest of my family. There is fighting there between the government and al-Shabab. My relatives escaped and are still hiding in the forest,” she said, sitting next to a sickly child in a small hospital in Baidoa.

Other women recounted that their husbands and older children were prevented from leaving areas controlled by the militants, denouncing years of extortion by the group.

Baidoa is not completely surrounded by al-Shabab, but it remains a precarious haven.

Officials from international aid organizations and foreign journalists travel under security escort and any travel beyond the city limits is considered extremely risky.

“We’re seeing populations under siege. Sometimes it’s hopeless,” said Charles Nzuki, who heads the United Nations children’s fund, UNICEF, in central and southern Somalia.

According to some estimates, more than half of the population affected by the drought remains in areas controlled by al-Shabab. Efforts to reach many communities have been complicated by US government rules preventing any assistance from benefiting designated terrorist groups.

International organizations and Somali authorities are working with local partners to increase access to aid and are planning airdrops in some disputed territories.

Still, one aid worker, who did not want to be named, acknowledged that it was almost impossible to guarantee that food or funds would not reach al-Shabab.

“Let’s not be naive, al-Shabab taxes everything, even cash donations,” he said.

Over the years, the militant group has built a reputation not only for violence and intimidation, but also for delivering justice in a country with a widespread reputation for official corruption.

In at least four villages near Baidoa, al-Shabab has a network of courts that apply Sharia law. Residents of Mogadishu and elsewhere routinely use these courts to resolve commercial and land disputes.

Further to the northeast of the country, local communities and militias from various clans have suddenly risen up against al-Shabab, now backed by the central government, and managed to drive the group out of dozens of towns and villages in recent weeks.

Military successes have sparked a groundswell of optimism, but it is unclear whether that will help in the fight against famine or simply distract the Somali government.

“It might, or it might not help. I think it might create more civilian displacement. Or maybe the government will manage to liberate more areas and people will have more access to help. We are looking at several possible scenarios,” said Nasir Arush, a local minister.

In Baidoa itself – a city of narrow cobbled streets marked by decades of conflict and neglect – the prices of basic products, such as rice, have doubled in the last month.

Many residents blame the drought, but others are also looking further afield.

“Flour, sugar, oil – everything has increased. Sometimes we have to skip meals. I heard about the war between Russia and Ukraine. People say that is the main cause of these problems,” said Shukri Moalim Ali, 38, as he walked toward his barren orchard.

While fighting to prevent deepening famine is the immediate focus in this region, Somalia’s new government is also looking to the future, trying to address more existential issues.

“It is a challenging task trying to respond to the drought, fighting al-Shabab and campaigning for international funding for climate justice,” said Abdirahman Abdishakur.

“We have a young population, a huge diaspora and strong business skills. That gives us hope. It is a challenge, but we have no alternative.”

Source: Elcomercio

I, Ronald Payne, am a journalist and author who dedicated his life to telling the stories that need to be said. I have over 7 years of experience as a reporter and editor, covering everything from politics to business to crime.

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/UBQL5W6FGJCZZIXRZYQK7FPPGQ.webp)

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/OC6M24QYRNFSNM7KCR7UUFIIJI.jpg)